The horror genre seems destined to be eternally underrated, as its muscular nature and its impactful and often distasteful imagery seems to overshadow the complexities of a genre that has lived through the artistic tradition of humanity from the beginning of time.

Horror is, in some cases, the best genre to analyze some of the philosophical themes of a specific period, as the message is more penetrating because it is injected through fear, one of the most natural and instinctive responses. Since horror cinema is primarily a cinema of sensations, it is possible, through these sensations, to create parables that tackle the most abstract and transcendent subjects in a way that is immediately perceived and has universal appeal.

This is one of the reasons why horror cinema remains endlessly popular and is the most international genre of them all, as if it taps into a collective soul that is shared by everyone; something internal, buried within and intuitive, that is common to all people.

10. Sauna (Antti-Jussi Annila, 2008)

“Sauna” is a great existential horror film. After all, Scandinavia is the land of Ingmar Bergman, and although Finland has a much less scintillating cinematic tradition, some of that genius must have reached the creators of “Sauna”. The film is set at the end of a war, in the 16th century, and is concerned with sin, guilt, torments of the soul, the nature of killing, and expiation.

“Sauna” is so contemplative and existential that it has to necessarily get out of the constrictions of the horror genre, which makes it a very unusual horror film, one that’s very atmospheric. The symbols are many, the ending is not straightforward, with the sauna, water, fire, and innocence.

The central theme is, however, man alone with his demons, his subconscious, and his mistakes; that’s probably the scariest part of the film, the idea that you can find yourself in a forest, a silently calm lake, gelid weather, and you’re alone, with yourself, your pain, your mistakes, the evil you caused and the evil you saw, and the damnation of human conscience.

9. House (Nobuhiko Obayashi, 1977)

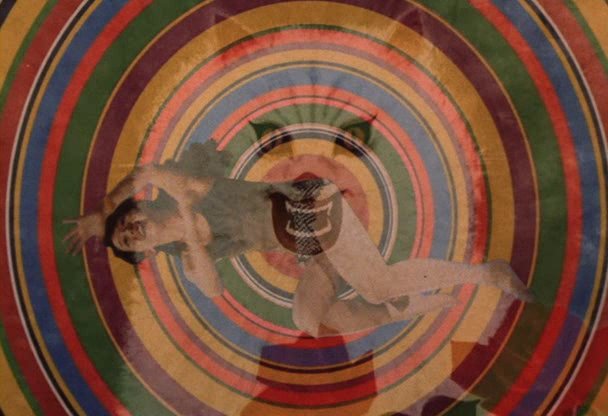

“House” is a weird psychedelic arthouse grindhouse horror film from Japan that has achieved cult status, after initially bad reviews and limited availability for many years. It is the prime example of what experimentation in genre cinema could lead to during the 60s and the 70s.

The film is incredibly hallucinogenic; the cosmic explosion that includes painted backgrounds, erratic editing, almost unfollowable plotting, freeze frames, surreal visions, and cartoonish explosions of violence give the film a sense of pastiche that is perfectly postmodern, but it’s still a Japanese film, and so under all the weirdness, there is deep social commentary, especially about the post-atomic generation and post-war Japan, and a sense of lost youth as well.

The meaning of “House” is to be found in the many explosions of colors, remembering the fire of the bomb, the deformation of the bodies, and the liquids are tears and blood. In many ways, “House” is also an evocation of lost childhood, an instinctive response to the horror of the world through an apparently incoherent, but colorful, improvisational, and ultimately quite deep Japanese arthouse horror.

8. Martyrs (Pascal Laugier, 2008)

“Martyrs” is known for being one of the best films of the New French Extremity, the French horror movement of the 21st century, and it is known for its brutal violence onscreen.

The first part of “Martyrs” is pure, cold, dark violence that comes quickly and without commentary, and pushes a sense of realism; everything changes when the twists start coming, the soundtrack starts to exhibit a sense of pietas, a pathos, emotional tension toward the horrible sufferings, the disgusting visions that hit the spectator, and the torture porn inflections start to become more baroque and more hybrid.

The true objective of “Martyrs” is transcendence, the idea that feeling pain can lead us to the light, to the truth, the idea that feeling for somebody else’s pain can purify us, that we can explore ourselves while discovering how much pain we can endure.

The final act of the film explores religious, spiritual and philosophical territories that are fused with the structure of a thriller-horror film. Very few films that borrow from the torture porn / splatter genre achieve such a level of profoundness.

7. Possession (Andrzej Zulawski, 1981)

Before “Antichrist”, there was “Possession”. Andrzej Zulawski’s film was particularly made for the time in which it was shot, so much so that is was banned in Great Britain for awhile, but it also allowed Isabelle Adjani to give one of the greatest film performances of all time (rightly celebrated at the Cannes Film Festival), and elevated the body horror genre to new metaphysical heights.

What sets apart this film about marital relationships, obscure political intrigues, and monstrous octopus monsters, and elevates over other sleazy examples of horror cinema of the time, is the thematic depth that Zulawski allows to be discovered through his clinical directorial eye, and the disorienting and terrifying twist in the staircase scene at the end, a disturbing sequence that explores different classic horror themes; the other, the double, the devil woman, the nightmare, insanity, and blood and guts.

The film could be described as a more abstract version of “The Exorcist” by William Friedkin, in which the spiritual themes are treated under a much more psychological, psychosexual, and ultimately metaphysical lens, with nods to the study of the subconscious, the return of the repressed, bestial urges, and paranoia. Somebody even hypothesized that the plot was about alien abduction.

The iconic scene of the wide-eyed Adjani, with blood dripping from her mouth, evokes more than one masculine fear, a fear that is ancient as the human race but is declined brilliantly in a modern setting with modern references, for a film that has become legendary.

6. Antichrist (Lars von Trier, 2009)

“Nature is Satan’s church.” A year after “Vinyan”, a far more celebrated director made a film about the woman as a terrifying otherness (something that relates partially to Freudian theories), about nature as the domain of chaos, and about the horror of grief, depression, and the irrational impulses that come to kill the patriarch, kill God, and celebrate a Sabbath of senses and doom.

Lars von Trier made this crazy film, one so brutal, so abrasive, so wild, so experimental and so unashamedly Tarkovskian, that the imperfections become carriers of meaning. The negative theology of the film is equally fascinating, as the three beggars carry an unparalleled symbolic power.

The film also tries to venture into meta-cinema, as it is a study of the director’s own depression and of his fear of women. In a way, in von Trier’s mind, the forest is the theater of the final battle between the order, the patriarch, Christ (Willem Dafoe) and chaos, the woman, and the Antichrist (Charlotte Gainsbourg).

The sense of shrieking hysteria that the film evokes is also very psychosexual; it’s a view of sexuality as an eternal damnation, a mechanism that enslaves every person to its biological origin, a mechanism that condemns men and women to eternal pain, eternal tension, to the eternal return (the fox that eats itself), and the eternal cycle of history.

One could see the liberation of the infinite power within every individual as one of the themes of “Antichrist”; not so much a film about destruction but a film about liberation, although the apocalyptic element is much more immediately notable. The film shares the same state of mind of some of best black metal music. “Antichrist” is a cinematic suicide, gritty and at the same time uplifting and richly metaphoric.