Cinema is an ever-evolving artform that uses picture and sound to deliver stories; make people laugh; express one’s self; educate the masses; or to send a political or philosophical message. If ever there were a little sibling to the cinema, it is without a doubt television.

While the two mediums have a great deal of similarities, the vast majority of TV directors throughout the past twenty to thirty years have had little to no regard for the virtuosity of those who also spend their waking hours behind a film camera.

This is largely due to the time crunch that is forced upon the studio giving them a “let’s get this over with” attitude. Luckily, there are still those in the television industry who put in the necessary immersion to produce quality episodes that exemplify the beauty of cinema.

To clarify, a show being mentioned means that most all scenes in any given episode exhibit a clear purpose to its shot composition.

If it is clear that the subject of the shot and what the images are supposed to mean to the viewer had delicate consideration and the execution was elegant aside from the sake of being elegant, it is considered cinematic. The ten series below are perfect specimens of those standards.

10. Twin Peaks

David Lynch’s surreal mountain murder mystery employed imagery that was a typical, run-off-the-mill film noir on severe hallucinogens. This beautiful and complex narrative demands multiple viewings due to its wildly unusual pictures that inspired better television.

When creating a show as inventive as Twin Peaks, one’s worst enemy can sometimes be the getting caught up in the technical aspects of filming, especially when it comes to special effects. “I don’t think about technique.

The ideas dictate everything. You have to be true to that or you’re dead.” (David Lynch The New York Times Magazine, January 14, 1990).

Lynch recognizes that the job of the director is to imagine how each scene ought to appear on screen and to communicate that vision to the crewmembers that are trained experts in their field. It is this professional approach to movie making that ensures excellence in every way.

Lynch often speaks on how film, like music, needs ebb and flow. As previously remarked on the works of Hitchcock, Twin Peaks has pulse. World-renowned musicians appreciate the importance of dynamic contrast, they know forte from piano.

If a film or series has the same artistic acknowledgement, the audience will become deranged addicts of your product. So much so that they will wait twenty five years for the elaboration of a cliffhanger to a season finale.

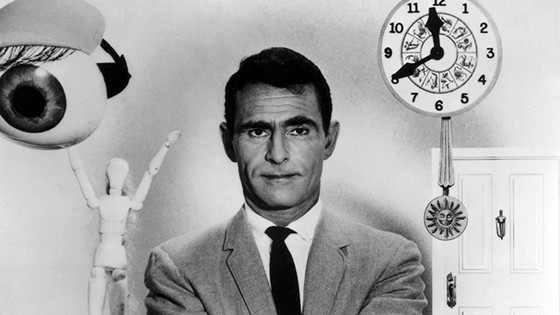

9. The Twilight Zone

Rod Sterling’s sci-fi pioneer is now considered a superb feat of storytelling. Laced with social and philosophical commentary presented with the chilling narration of the shows own creator and writer has proven itself timeless.

Along with Sterling’s engaging insight on abstract issues, students of film can all observe and appreciate the visual brilliance that was itself was, in reality, more of a lucky triumph of problem solving than anything else.

The dilemma that faced the television producers of old was the need for an incessant amount of celluloid film stock, a product which was, is, and will likely always be, a marginally expensive piece of equipment.

This is especially true when one needs it for a series of short films that are being broadcast on a weekly basis. It seemed that the only true solution to this predicament was to encapsulate multiple aspects of a scene in one shot.

Actors would be blocked such that the recipient of bad or shocking news would be in front and slightly off-center while the deliverer of said news is in the background, placing both action and reaction in the same frame at the same time. All of a sudden, the whole exchange is more dynamic while still feeling authentic to the viewer.

8. True Detective

With the wave of overt political correctness and activists for family values in contemporary civilization , storytellers are cautious to create content that will offend as few people as possible by censoring language with euphemisms or downplaying the behavior of certain character archetypes to not come off as chauvinistic.

From a perspective of etiquette, this is a very positive thing. However, such etiquette is irrelevant to art and more often than not results in dishonesty of setting or character. True Detective’s recognition of this distinction is evident in every aspect of is composition.

This HBO drama takes place in a town deep in the American South (Louisiana to be specific and to further the point). In a such a redneck community there are a few underlying, yet horrific truths; women are treated as sexual or romantic pawns; people of color are seen in a different light; secular points of view are heavily antagonized, etc. True Detective, instead of shying away of these facts, embraces them to tell a more compelling story with thicker tension.

Parallels are often drawn between the honesty toward this show’s cultural source material to that of Roman Polanski’s Chinatown. Namely, how masculinity is heavily lionized and is often triumphed over femininity to make the latter seem less like a counterpart and more like a sideshow.

This is exhibited in the conduct toward women whether pure or wicked at heart, the choice of wardrobe for the actresses, and even their blocking such that they are in a less flattering position than a male.

Yet, in the midst of this misogynistic environment, the directors of this show present a psychological conflict of its most “macho” characters. Some of the more virile acts that the male protagonists perform are paired with an extra, juxtaposing factor.

These include music choice or facial expression or the reaction of fellow characters, that deemphasize the brawn of the behavior to a weaker state. The cinematic finesse needed to pull off such advanced, mature, and complex technique of characterization is more than deserving of a spot on this list.

7. The Sopranos

Tim Van Patten is one of the biggest names in television today. He is credited as a director for Boardwalk Empire, Deadwood, Ed, Game of Thrones, The Pacific, Rome, Sex in the City, and The Wire. The aforementioned programs already make for an impressive filmography even without the pièce de résistance that is The Sopranos, an HBO Italian-American mafia masterwork.

The artistic purity of this series is derived in part from respecting the titans of its genre. Chief among these titans being, naturally, Martin Scorsese. Though it has been a decade since his last mafia film, his influence on the genre has yet to be equalled.

Gary Edgerton, dean of the College of Communication at Butler University, wrote in his 2013 book that shares the show’s title that creator David Chase “readily acknowledges Scorsese’s ‘tremendous influences’ on him in subject matter and stylistics,” (Edgerton, 40).

Avoiding copycat status, the folks behind The Sopranos recognized that Scorsese’s style is a safe platform to launch brave new creative scenarios involving the mob from. On that basis, they could not go (and never went) wrong from a cinematic perspective.

The topic that the creators of The Sopranos used to spawn away from the inspiration and Martin Scorsese was the visualization of the relationship that a mob boss has with his family if they were to live in the family friendly suburbs of the United States in the 1990s.

Namely, how the typical housewife of that culture would respond in such a circumstance. This idea paved the way for many interpretation of that premise, resulting in the likes of Breaking Bad, Mad Men, Deadwood, etc.

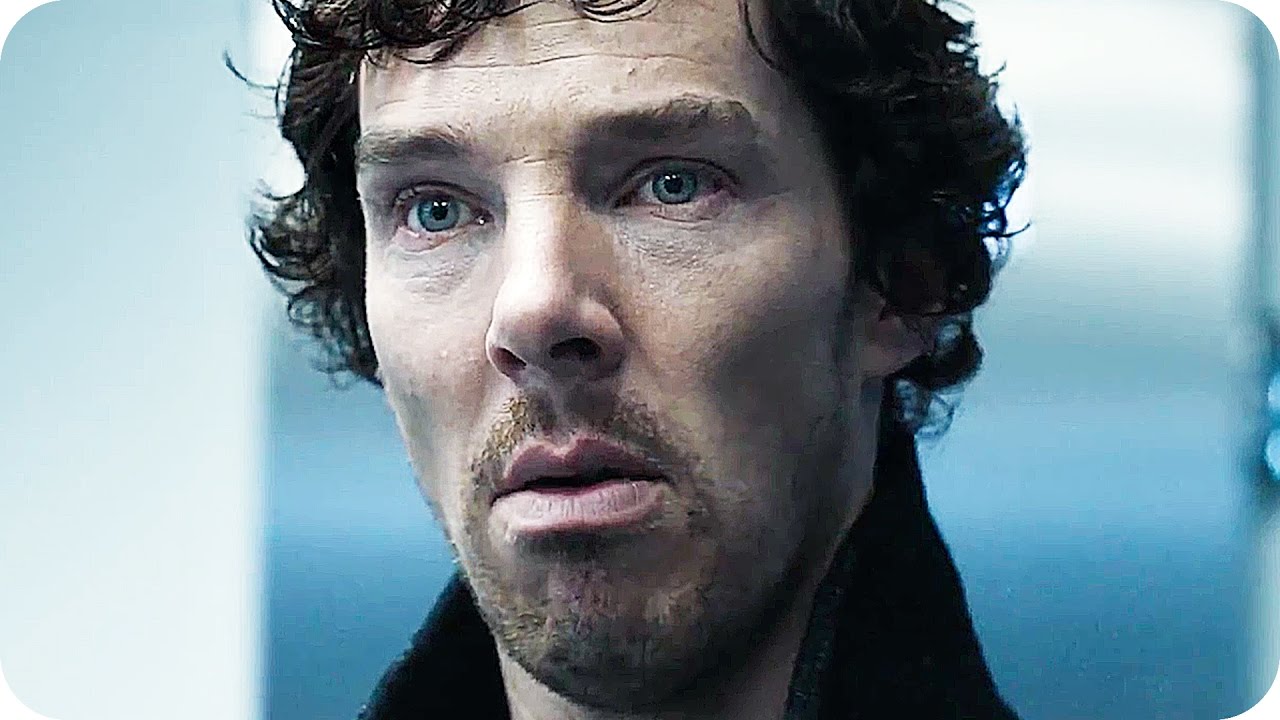

6. Sherlock

Sir Arthur Conan Doyle’s brain child Sherlock Holmes is one of the most enduring fictional characters of all time. His many stories have been told time and time again or entirely new fables have been manufactured with his likeness.

A great deal of these reimaginings have been created on celluloid in feature films. Yet, much to the shame of die-hard fans, they have not always provided the source material the courtesy of being at the very least inventive.

The BBC presentation of Sherlock created and written by Mark Gatiss and Steven Moffat is anything but a regurgitation. It is a thoughtful homage to both the original tales as well as a means for challenging the possibilities of the medium at this point in its evolution.

While sticking to the beloved idiosyncrasies of the characters, settings, and plot points of Doyle’s books with only the adjustments necessary to fit in the backdrop of the contemporary world, frequent director Paul McGuigan explores methods of filmmaking, from first draft to final cut, that are revolutionising the very fibers of the artform.

Traditionally, a character’s thoughts are visualised by aiming the camera at the subject of thought or some abstraction thereof and cutting to the actor’s reaction.

This is a formula that has been used for decades even when it’s not helpful in the development of character. McGuigan and the like refuse this basic tactic in illustrating Sherlock’s thoughts by accurately portraying the behavior of the human mind.

As Benedict Cumberbatch rolls through his observations as fast as a person can possibly articulate while still being comprehended, small snippets of the subject slide through the screen often paired with text labels and highlighting to emphasize the components of a crime scene that might help the detective.

When he’s done showing off, it cuts back to Sherlock’s calm and collected face as everyone else stares awestruck at the high functioning sociopath.

The audience is not watching this with the astonished feel of John Watson or Inspector Lestrade, but with the smug of Sherlock Holmes. Why? Because they just took a fifteen second turn being him. Giving that illusion is the very essence of the cinema.