Hollywood’s “Golden Age” (spanning from the late 1920s-1960s) solidified many standards of cinematic narrative, aesthetic, cinematographic construction and performance and studio systemization. The effects of the standardization of film-making during this time still reverberate to this day, influencing the films, writings and art of today’s most celebrated filmmakers, critics and screenwriters.

The hold that the Hollywood Golden Age has upon our shared cultural consciousness shouldn’t be discounted either. Film (and its history) is embedded within the collective memory unlike any other medium due to its vast proliferation and ease of access. Films from the Golden Age, ones that are nearly one hundred years old, continue to be referenced within the annals of popular culture.

The staying power of the Golden Age lies within the universality of its narratives and perhaps within the power of the illusive filmic image. The feeling of magic that stays with us when we exit the theatre is the same feeling as that of our parents, grand-parents and even great-grandparents as they experienced cinema throughout their lives.

In this way, film has become a representative of the generational experience, age-old narratives becoming renewed by the virtue of their retelling in situations or environments significant to a newer generation.

Below are 10 films inspired or influenced by the Hollywood Golden Age, continuations of the method, aesthetics or renewals of such. Ancient stories, renewed through the lens of contemporaneity.

10. Hail, Caesar! – Joel & Ethan Coen

The Coen Brothers’ Hail, Caesar is inherently and obviously linked to the Golden Age mythos of classical Hollywood. The narrative ties into Hollywood’s use as a form of propaganda used to impart the ideological aims of the United States’ capitalism v. the socialism of the then-USSR.

The Coen brothers use Cold War paranoia and the philosophy of H. Marcuse to demonstrate the power of the moving image upon the mind and how this understanding of psychology was used in film (specifically the Golden Age) in order to influence the American Public into supporting the government of the United States.

Of note, of course, is that in using Marcuse’s rendering of commodity fetishism (upon his meeting with Clooney’s character) we see that the Coen brothers were aware of the subversion within the Hollywood system. In fact, through parable, the Coen brothers sort of are commenting on the state of cinema in the current era, that is films that seemingly support cerebral revolutionary or subversive ideas but in fact exist only to perpetuate dominant western ideology.

By using the techniques of The Hollywood Golden age, specifically with reference to the films of Hitchcock, Kazan and Preminger, they actually complete what could be termed a “double-subversion”, in that while the film seems to support a view of modern Hollywood as more open to subversive ideas, it understands and relates that the methods of the Golden Age are still in effect as a cultural paradigm. In order to subvert the history of the cinema, one must confront it, which is what the Coens attempt in Hail, Caesar!

9. High Anxiety – Mel Brooks

Brooks’ High Anxiety is notable in that in addition to its influence rooted in the Golden Age Suspense films of Hitchcock, it was also written and produced in collaboration with Hitchcock himself.

With High Anxiety, Silent Movie and Blazing Saddles Mel Brooks asserted himself as a master of pastiche, while retaining his ‘neo-screwball’ aesthetic that he developed as an independent filmmaker with films like The Producers and The Twelve Chairs.

While Silent Movie and Blazing Saddles are indeed shining examples of the Golden Age’s influence upon Brooks’ comedy and cinematographic style, High Anxiety is perhaps the most lucid and masterful exploration into Brooks’ understanding of how the stylistic underpinnings of Golden Age-era filmmaking can be manipulated to fit the social context and understanding of a different era.

He uses methodology developed by Hitchcock himself and subverts them, poking fun at the way Hitchcock is able to lead the viewer into a state of suspense. In this way, Brooks’ illustrates his understanding that the manipulation of images can be made to fit different contexts based simply upon minute fractions of editing, chronological manipulation and auditory clues.

Perhaps as an overall piece, the film may not be Brooks’ at his best (particularly his work as lead in the film), but his directorial prowess proves that Brooks knows that the methods and standards of Classic Hollywood can be used to subvert themselves.

8. Collateral – Michael Mann

Mann’s Collateral is infused with characteristics typical of Golden Age-era suspense flicks and thrillers. It seems thoroughly modern, however though it was shot on then-new digital Sony CineAlta HD cameras, its modern look belies its stylistic origins.

The seeming perfection of the digital image is actually subverted by Mann’s use of the camera in dark environments, which rather than removing the imperfections of a film print and replacing it with the perfect pixel renderings actually seeks to showcase the imperfection of the digital image, showcasing how digital film capturing in low light actually replicates the moody graininess that is typical of suspense films of the Golden Age.

The narrative itself, concerning Jamie Foxx as a hitman moonlighting as a cab driver is rooted in the mystique and mystery of 1950s paranoid-thriller mythology, perhaps alluding to the films of John Sturges, Preminger and Fritz Lang (who all were enamoured with moody dark locations and focuses upon those who live and work in the early hours of the day).

7. Les Diaboliques – Henri-Georges Clouzot

Released as Diabolique in North America, Clouzot is perhaps anomalous within his context as a French filmmaker in the 1950s.

While his contemporaries were making films that while still indebted to Hollywood cinema of the time, were less inclined to inherently reveal their homages to Hollywood and rather relied on the reference points of their audience to deduce their Golden Age influence, Clouzot decided to perhaps display his prowess at crafting a film so similar to his American counterparts (and yet surpassing them) that it would indeed become one of the classics of the suspense and horror genres.

Clouzot’s understandings of filmic Hollywood thriller grammar was so astute that its clout as a mystery film left even American critics claiming it as one of the best thrillers ever designed, with Roger Ebert stating in 1995 that; “‘Diabolique’ is so well constructed that even today it works on its intended level”.

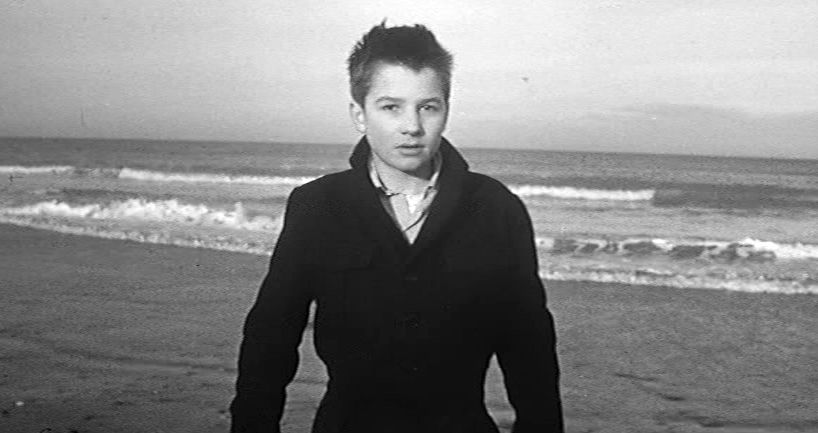

6. The 400 Blows – Francois Truffaut

In contrast to Les Diaboliques, Truffaut’s coming of age film, The 400 Blows is itself rooted in the cinema of Alfred Hitchcock, but translates its cinematic heritage in a vastly different way.

Instead of utilizing the more lavish cinematographic methods of Hitchcock (such as those employed by Clouzot in Les Diaboliques), he uses some of the more infrequently used tools Hitchcock used in his films, such as the first person perspective that Truffaut co-opts from films like Rear Window or North by Northwest, or his use of establishing shots of Paris which were reminiscent of Hitchcock’s use of establishing shots of cityscapes (such as London, San Francisco, etc.) in order to provide a sense of geography or perhaps intimacy.

It’s this sort of intimacy within the context of a cinematic reality that both Hitchcock and Truffaut were acutely aware of. By framing objects or locations of significance within the perspective of the character imbues the viewer with a sense of empathy or perhaps understanding (either of the character’s emotions, motivations, history or all three.).

Though Hitchcock was renowned as a master of suspense, he also had a keen sense of the nature of empathy and how it can be used to engender a greater sense of reality within the world of a film. Truffaut knew this well and employed these techniques to great effect, which at the time hadn’t been used frequently in autobiographical works, which tended to be presented more melodramatically.

The scale of an intimate relation to a character forces the audience into a more introspective mood, providing the film with a greater emotional depth. This is perhaps one of the greatest legacies of Hitchcock, in that through his intimations of empathy, even through seemingly inauspicious thriller films, he allowed the formation of a generation of filmmakers to explore the profundity of character in ways that could more readily capture an audience.