“[Dead Man] is the Western Andrei Tarkovsky wanted to make.”

– J. Hoberman

The Place of Dead Roads

Ohio-born Indie auteur Jim Jarmusch refurbishes the black-and-white Western the way a 19th century Native American might see it––as a murderous and genocidal head trip heralding the deadly homecoming of capitalism. Woven into the light threads of this gossamer nightmare is a warm and rewarding friendship between one William Blake (Johnny Depp), a wavering, dying accountant from Cleveland, and Nobody (Gary Farmer), an outcast Indian.

Their visionary voyage into the American north-west uses Jarmusch’s signature minimalist and informed style in a film that most likely couldn’t exist in a post-Blood Meridian, post-Place of Dead Roads universe (hyper-stylized and literate Revisionist Western novels of great weight, by Cormac McCarthy and William S. Burroughs, respectively). Perhaps the darkest, most shocking film in Jarmusch’s considerable oeuvre, Dead Man is also his most far-reaching and confrontational.

“Jarmusch has long made a specialty of seeing the United States through the eyes of outsiders: immigrants and tourists whose perspectives grant a new window onto America. It’s central to the politics of Dead Man that the designated role of the foreigner is filled by a Native American, a sardonic comment on the fate of the land’s original people in both history and movie mythology.”

– Dennis Lim, The Los Angeles Times

Rage against the machine

Depp’s William Blake sticks out like the proverbial sore thumb in his plaid suit and dorky Poindexter glasses. Timid, hilariously cosmopolitan, and hyper-civilized to a fault, we first meet the mid-western accountant William on a train journey that feels endless.

Rather reluctantly William finds himself lost and at odds in a strange conversation with the train’s soot-covered fireman (Crispin Glover) and it’s through this discourse and the barbaric behavior of the other passengers––the begin firing out the windows of the train at a grazing herd of buffalo––that this is something like a funerary procession or an elevator to hell careening William towards the frontier town of Machine.

Once in Machine, William’s luck doesn’t improve, it gets worse and that sinking feel is palpable as disorientation and unfriendliness seeps in. It’s not just Neil Young’s dissonant caterwaul guitar score that unnerves and perturbs.

William witnesses a succinct yet agitated series of tableaus including a braying horse pissing in the street, and a threatening-looking man (Gibby Haynes of Butthole Surfers fame) receiving a blowjob from a prostitute, who locks eyes with William and draws his pistol upon him. These brief but bombastic spectacles lead William to the metal works and the reason he’s made this western migration, for he was promised an accounting position.

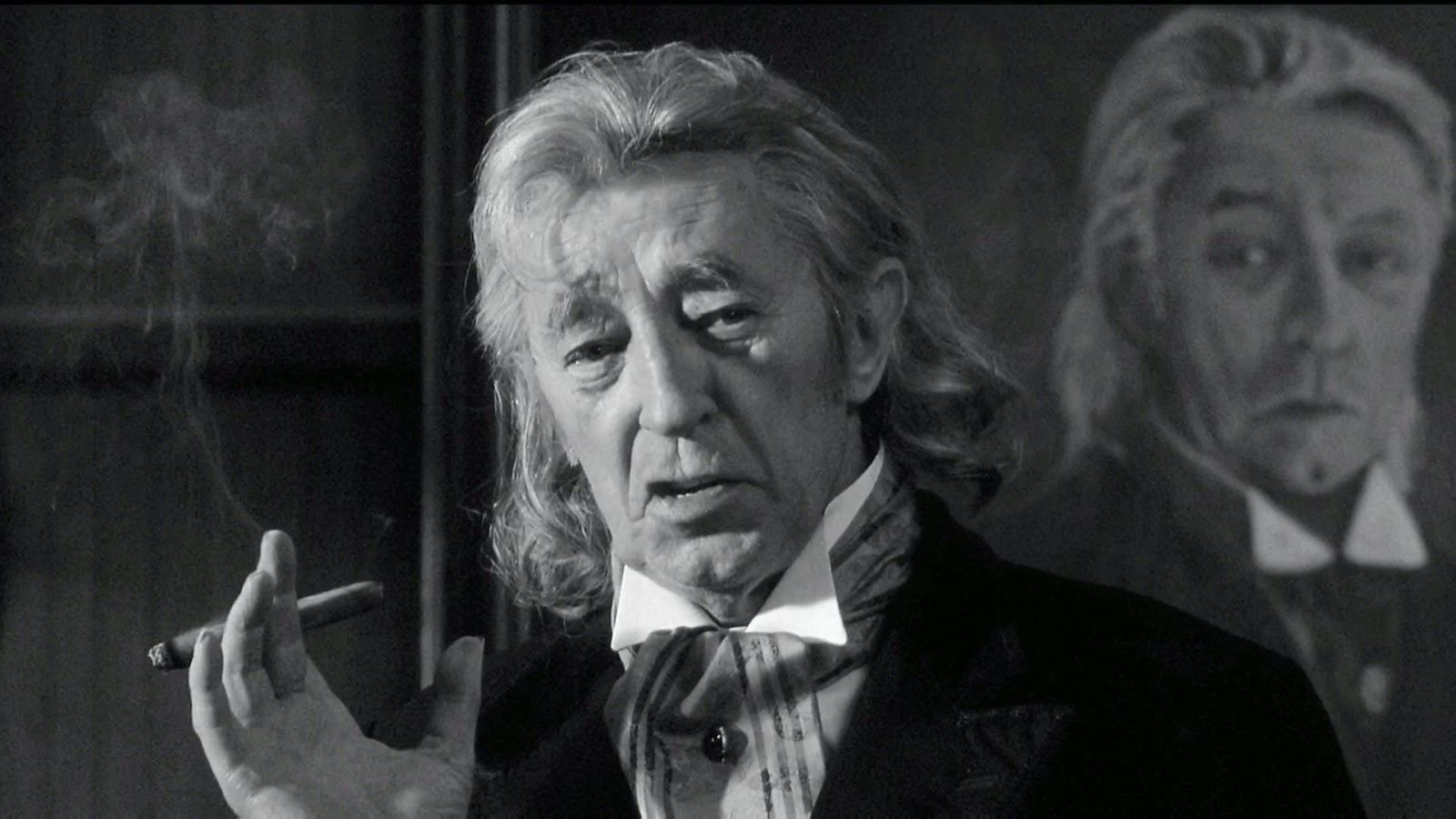

It’s soon revealed via the company’s combative proprietor John Dickinson (played by a wonderful Robert Mitchum in his final film role before his death in 1997) that William’s position was filled months ago. And to get William out the door with alacrity, John fiercely points a double-gauge shotgun into his face as a fuck you.

Down in the mouth William makes his way to a saloon to spend his last little bit of dough on a flask of whiskey. At long last but only fleetingly William’s luck seems to favor him when he meets the lovely Thel Russell (Mili Avital), a former prostitute selling artisanal paper flowers at the saloon.

Thel, it’s worth noting, is named for “The Book of Thel”––a 1789 poem by Blake. In short order the two fall into bed together but their passion is transitory as they are interrupted by Thel’s ex-fiancé, Charlie (Gabriel Byrne). Enraged and way out of line, Charlie fatally shoots Thel, severely wounds William, and is shot dead by William in return.

“As a tale of innocence lost, Dead Man is the indie flipside of The Birth Of A Nation (1915), stripping away D. W. Griffith’s racist triumphalism to reveal a wilder, weirder and altogether more spiritual side to America’s national identity. Here Jarmusch shows his unconventional way around the edges of genre cinema… …and the result is a low-key classic of strangely poetic beauty––a western for sleepwalkers and dreamers.”

– Anton Bitel, Eye for Film

Every night and every morn, some to misery are born

After the tragic deaths of Thel and Charlie, William flees with haste, stealing Charlie’s pinto, which he can barely ride, thus beginning an odyssey through the wilderness of the American West. By the early dawn William meets the enigmatic Indian named Nobody (Farmer) who right away recognizes William’s severe injury and the bullet close to his heart.

Nobody eschews the archetypal and frankly racist stereotype of Noble Savage as we get to know this unconventional outsider. An outcast amongst the Blackfoot people (his father was Blackfoot, his mother Blood), Nobody was primarily raised by whites who abducted him at a young age, and later when he tried to return to his people he was given the derisive moniker “Exaybachay” which means “He Who Talks Loud, Saying Nothing”.

Bit by bit suffering from his untreated bullet wound which, as Nobody rightly suspects, is fatally too close to his ticker, William steers toward his death. Believing William to somehow be the reincarnation of his namesake the seminal English poet and painter of the Romantic era, Nobody becomes William’s guide, well aware that this charge will include seeing his guarded entry into the spirit world.

“Do you know how to use that weapon?” Nobody asks William, referring to his gun. “It will replace your tongue. You will learn to speak through it. And your poetry will now be written with blood.”

“I’m not dead. Am I?”

– William Blake (played by Johnny Depp)

Stupid fucking white man

Unbeknownst to William and Nobody, Charlie, the man William shot and killed in self-defense, was the son of John Dickinson––the shotgun wielding, cigar chomping industrialist son of a bitch.

Dickinson, extra annoyed with William for stealing his son’s horse like a “up yours” gesture, brings in three badass bounty hunters––Johnny “The Kid” Pickett (Eugene Byrd), Cole Wilson (Lance Henriksen), and Conway Twill (Michael Wincott)––to bring William in. Dead or alive, it makes no difference to Dickinson, who also puts a sizeable bounty on William, guaranteeing a large manhunt for our forlorn standard-bearer.

The bounty hunter posse under Dickinson’s employ have an infamous prestige about them; The Kid is a cocky, cold-blooded killer, Twill has a fearsome reputation and a motormouth, but most notorious amongst them is Wilson. Wilson, Twill warns the Kid, is dangerously bonkers. Not only has this nutjob “fucked his parents”, “both of ‘em”, he “killed them”, “fucked them again”, and then the coup de grâce, “he ate them”.

“You were a poet and a painter, William Blake. But now, you’re a killer of white men.”

– Nobody (played by Gary Farmer)

Drive your cart and your plow over the bones of the dead

A pensive and at times almost surreal dissertation on contemplation, Dead Man beguiles and charms through Robby Müller’s richly modulated and lush black-and-white lensing (Müller’s monochrome cinematography owes much to the late landscape photographer Ansel Adams) which is exquisitely accompanied by Young’s simple yet obsessive guitar score.

Also deserving praise is Depp’s gentle and fine-grained performance, wonderfully embodied in the memorable daydream-like sequence when he huddles down next to a departed fawn. Similarly, Farmer brings much nuance and loving guile to Nobody and, as Jarmusch fans are well aware, he would reprise his role in an amiable cameo in Jarmusch’s next film, Ghost Dog: The Way of the Samurai (1999).

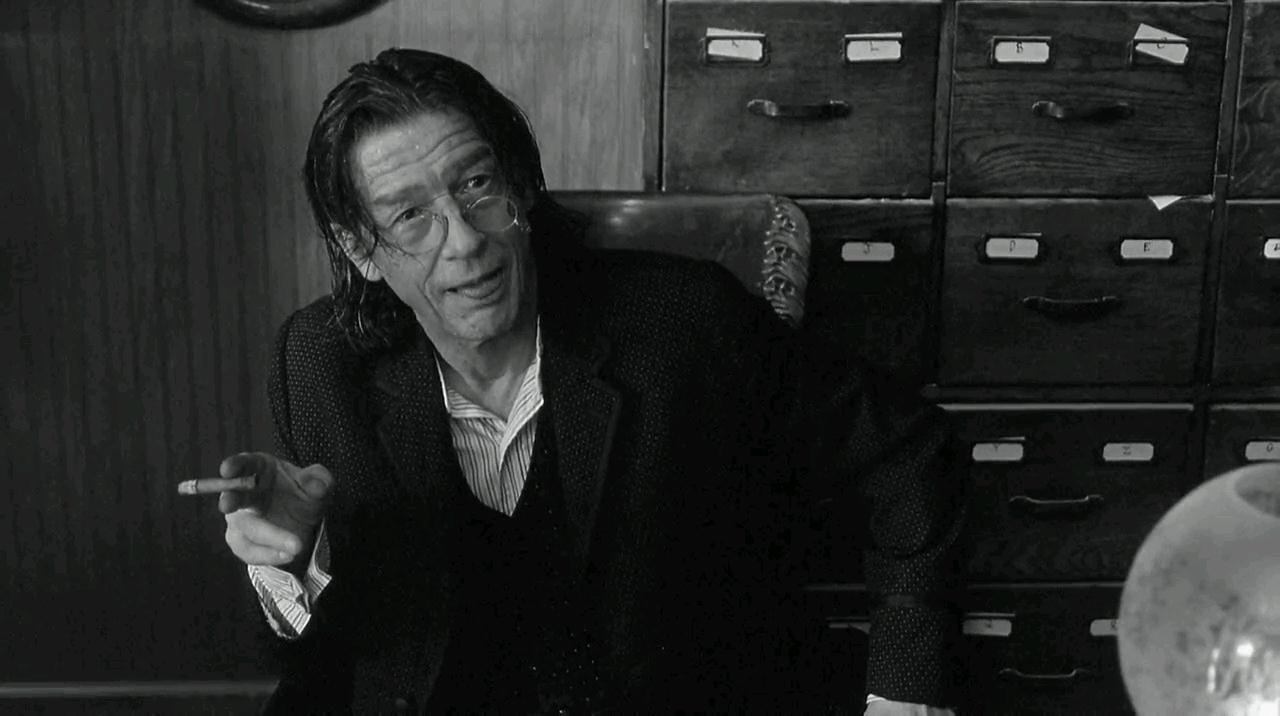

Although much of the cast have mentioned here already, Dead Man offers a wealth of surprising cameos and support roles from the likes of John Hurt, Alfred Molina, Iggy Pop, and Billy Bob Thornton, in a seemingly endless barrage of frontier chicanery and sharp-practice.

It is preferable not to travel with a dead man

Early in the film, when William is with Thel and it almost feels like the film could take a different trajectory into more tender and quixotic tracts, the two share a very revealing moment that seems to rear close to the crux of Dead Man. William asks Thel why it is that she’s carrying a loaded pistol and she answers back: “‘Cause this is America.”

Death comes swift and sudden for some of the characters in the film, and a great deal of the narrative and the ferocity therein is unpalatable, unromantic, and unheroic. Violent acts of murder are awkward, messy, and rough.

“In Dead Man [the use of violence is] not that unrealistic, because boom!––gun goes off and guys get hit with metal and fall down like puppets with strings getting cut––which is kind of what we wanted it to feel like. Shocking for a brief moment and then very still. Someone’s soul got taken.”

– Jim Jarmusch

Some are born to Sweet Delight, some are born to Endless Night

The great Western chasm, the vast emptiness and the overspread silences permeate Dead Man, accompanying William and Nobody through the forests, through to the threatening trading post, and to the denotative icy waters of the river that brings the pair to the Makah village. Nobody may well be something of a Virgil to William’s Dante but when they are given brief asylum by the Makah tribe it has more to do with Nobody securing a sanctified canoe for a boat grave.

It’s refreshing too that Nobody, the rites and rituals he performs and his exchanges with other natives is never fully comprehensible for William or for us. Jarmusch deliberately eschews the use of subtitles or translations so that the conversations carried out in Blackfoot and Cree language are there entirely for members of those nations. This includes in-jokes and intimations directed solely for Native American audiences. Respect.

As Dead Man approaches the adjournment we find William in the spirit-canoe, Nobody at his side to launch him off, and a final mythic visage as the vessel glides far afield. A death trip tenor with an Arthurian undercurrent, and a welcoming return to conception.

Author Bio: Shane Scott-Travis is a film critic, screenwriter, comic book author/illustrator and cineaste. Currently residing in Vancouver, Canada, Shane can often be found at the cinema, the dog park, or off in a corner someplace, paraphrasing Groucho Marx. Follow Shane on Twitter @ShaneScottravis.