Towards the end of Ex Machina, I remarked to my viewing partner that we were watching Ava as a human, to which she responded in the affirmative. And so, Ava had passed the Turing test, invigilated by oblivious participants from beyond the fourth wall.

From psychological microcosms to philosophical thought experiments, Alex Garland had really done his homework. Covering the intricacies and implications of AI is never an easy task, filled with speculation and conjecture, but this movie makes a sublime effort. One that must be applauded. One that is perfectly coalesced by Alicia Vikander’s sublime acting.

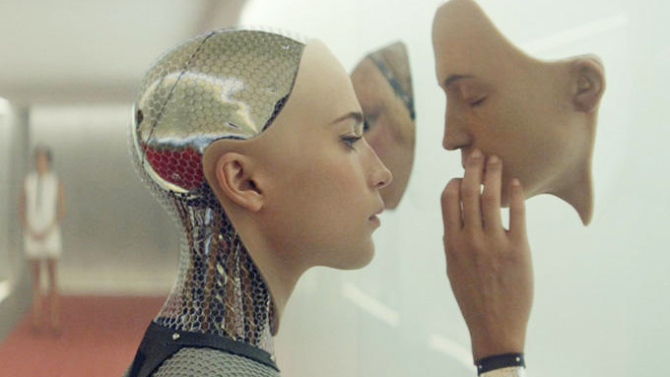

Her movements – the batting of her eyelids, the twitch of her lips, every micro-expression – was a testament to the conundrum that is the Uncanny Valley. Her walk, her posture, her gesticulations, her hesitancy, were all executed with a measured grace that defied humanity with eerie precision, and yet it was strangely human.

Her moments of vulnerability were enacted and exemplified with jarring fluidity, blurring the line between human and android, and bridging the chasm of the Uncanny Valley. Her design, unlike anything we’ve seen on the big screen before, lent itself to the seemingly fragile and complex nature of her existence.

Alicia Vikander’s training as a ballerina was tailor-made to the execution of her role as Ava. Losing myself to the narrative, I couldn’t tell if it was a human playing a robot, or a robot playing a human, and that is a victory in itself.

Performances by Oscar Isaac as Nathan and Domhnall Gleeson as Caleb, although secondary to the eminence of Ava, flawlessly supplements the plot. Within a convoluted mosaic of deceit, the interactions between the two were dripping with tension and awkwardness. And rightfully so, as Nathan and Caleb occupy two sides of the same psychological coin.

Whereas Nathan is a secluded megalomaniac with a God complex, verging on insanity with undertones of misogyny, racism and aggression – one is occasionally forced to wonder if his persona is carefully calculated as a ploy to corner and toy with the “very quotable” Caleb.

Their intellectual skirmishes serve as platform for Nathan to patronize and challenge Caleb, coercing him to “engage intellect”. Consequently, we’re forced to wonder if his act is a part of the experiment. In all this, despite the insanity projected by Nathan, he exhibits a subtle foundation of logic and truth; misanthropic as it may be.

On the other hand, Caleb is a classic back-to-the-wall protagonist, thrown into an unknown experiment with unknown variables, and inevitably developing a savior complex. As the proverbial underdog, he is the one we root for to defeat odds that are clearly stacked against him.

He is empathetic and caring; yet his logic, upon close inspection, is privy to a higher dose of insanity as compared to Nathan’s (projected) persona. Together, they form a revolving chiaroscuro stained with character flaws and internal dissonance.

Taking into account that Ex Machina is Garland’s directorial debut, the camera work is truly exceptional, especially when considering that the genre has been diluted by special effects and CGI. The set itself deserves applause, as the detachment of nature is juxtaposed against the violence of intrusive technology. Slow moving takes were all that were needed to complement the setting and environment, contrasting between agoraphobia and claustrophobia.

In all this, the Ava sessions act as the narrative focal point, both in theory and technicality. The location begs the question, “who is the true subject of the experiment ?”, with Ava exercising free reign of mobility, and Caleb constrained to the confines of a cube. Within the sessions, the camera comes to life and speaks a language of its own.

Careful positioning conveys a subtle power struggle between Ava and Caleb, with angular dispositions used to highlight variances of dominance, submission and parity. In turn, personal and internal dichotomies are illustrated through the delicate use of reflections within the glass cube.

Nuances of subject and object, observer and observed, are also illustrated by the placement of the camera relative to the glass cube occupied by Caleb; “through the looking glass”, as earlier commented by “Mr. Quotable”, but the sides of the looking glass are indistinguishable from each other, without the translation provided by the camera.

Conceptually, Ex Machina is a comment on our semi/unconscious fear of technology that transcends our comprehension. From privacy issues and search engines that map human behaviour, to consciousness and sentience itself, it serves as a momentary spark in the darkness that pervades technological singularity.

“I am become death, destroyer of worlds”, as used in the film couldn’t have been more appropriate, as Stephen Hawking himself has drawn parallels between AI and nuclear power. Nathan posits that Artificial Intelligence will look back on us, like we look back on fossils, as primitive rungs in the ladder of evolution.

The future may be bleak, but it sheds light on elements of our own consciousness – who are we; what are we; what makes us who we are. Succinctly remarked upon by Nathan, we ” were programmed by nature and nurture”, and the implications are far-reaching.

The film’s use of Jackson Pollock aesthetically conveys the paradox of our nature, as “the challenge is not to act automatically. It’s to find an action that is not automatic.” Ex Machina invokes introspect on the scale of ourselves as a species, with scope that extends into the ether of consciousness.

The ending itself alludes to our inherent nature, that of selfish gain rooted in disconnected malice. Garland makes a very specific comment in an interview, which speaks volumes and tempers any accusation of technophobia – “My anxieties are about people. Not machines”.

Ex Machina doesn’t serve as a caution against Artificial Intelligence, it serves as a caution against our selves. If extinction befalls our race, we shall be the harbingers; architects of our own poetic doom – there’s an element of morbid comfort in that, isn’t there ?