Ready for the additional dose of eclectic cinematic weirdness? If your answer is affirmative, then have a look at another twenty films, which fit this category and originate from many corners of the world.

The criteria are the same as the last time, meaning you’ll find titles that belong not only to different countries, but to various periods, genres, mediums and their respective directors’ genders as well.

1. Closed Vision (Marc’O, 1954) – USA/France

Weirdness of the avant-garde kind

Closed Vision was named the most important experimental piece ever since The Blood of a Poet (Le Sang d’un Poète), and by none other than the auteur Jean Cocteau himself. The film’s epigraphs explain it as a unique attempt at recording a protagonist’s stream of consciousness, from nebulous thoughts to coherent ideas.

The audience is invited by the narrator to forget the norms of logic and rely upon general emotions. Soon afterwards, we are overflown by the hero’s inner voices, branded with hyper-theatricality, whilst supplementing the outlandish juxtapositions. Marc’O and his assistant Yolande DuLuart’s associative collages serve as “bridges” between fanciful vignettes.

The French Riviera is the place of bizarre occurrences, such as digging one’s own grave or the middle-aged couples brunch, which starts in laughter and ends in iconoclastic ritual. Children circle around the pole.

A sad, imprisoned blonde receives an apple and then a jackstone to her forehead. The heap of fake money is burned, carried in a coffin and plundered… Random and occasionally repetitive, artfully composed B&W pictures lull you into a wakeful, meditative dream, embroidered with dissonant sounds.

2. Miraculous Virgin (Štefan Uher, 1966) – Czechoslovakia

Weirdness of the New Wave kind

Štefan Uher, one of the foremost representatives of Czechoslovak New Wave, also cites Cocteau, but he does so via the allusions to the famous mirror scene from The Blood of a Poet. With great attention to the production design, he adopts Dominik Tatarka’s novel of the same name. Allegorical story, set in a Slovak town during WWII, focuses on the purity of imagination, its inexhaustible power and the loss of its innocence. While speaking of creative freedom, it follows a group of artists obsessed with enigmatic beauty Anabella.

Two narrative threads are intertwined into a mutable structure, which constantly shifts between dismal reality and surreal fantasy. The first one is spun by a painter Tristan, aspiring to portray the emptiness, whereby the other is from the perspective of a sculptor Raven, torn between his own desires and imposed tasks. From their nonconformist attitude stems a positive energy, which makes us forget they’re living under the German occupation.

As for Anabella, she is conceived as the ideal woman, as well as the embodiment of an abstract entity – creative force, collective dream, repressed libido and/or even death.

3. The Face of Medusa aka Vortex (Nikos Koundouros, 1967) – USA/Greece

Weirdness of the petrifying kind

Four people on an island – Filippos, with a girlfriend of his younger brother (murdered?), a homosexual Alexis and a shady stranger – are entwined in the web of lies, jealousy, remorse and hidden agenda. It’s also possible that they (and the viewer) are the victims of a “spider” Nikos Koundouros (Young Aphrodites), who weaves a complex (unsolvable?) puzzle.

By revealing a part of the crew behind the camera, the helmer dispels and, at the same time, strengthens the illusion of the film. Without a warning, he commences the game of obscure symbols, pulling you – unprepared and seduced by high-contrast B&W photography – into it. A plot (if it exists at all) and short dialogues are subjected to inspired imagery – the pieces of a broken dream.

Although he shoots on Crete, Kounduros is more interested in his characters’ faces – expressionless masks hiding Eros and Thanatos, as well as the titular Gorgon, behind. Their presence is felt at each moment, whether it’s in the sex scene, which transports us to a London-based apartment, or during the crafting of a scarecrow with a human skull. A summer idyll is mystified, but one thing is certain – Hera Angelousi’s unforgettable, penetrating look.

4. Good and Evil (Jørgen Leth, 1975) – Denmark

Weirdness of the anthropoligical kind

Good and Evil (Det gode og det onde) is probably one of the brightest examples of radically experimental cinema. It’s the extension of The Perfect Man (Det perfekte menneske), which Danish poet, critic and director Jørgen Leth used as a starting point for a series of unique anthropological studies.

Applying a twisted version of a child’s educational programs formula, Leth “fools around” with trivialities of everyday life in the course of ten chapters. The useful and the useless things are sorted out, prior to the analysis of thoughts, feelings and, ultimately, words.

Succinct explanations are provided in a soothing voice, with the author emphasizing the ordinariness of a depersonalized, psychologically empty homo sapiens. The proceedings are reminiscent of some whimsical, rehumanizing performance, with a comic relief once in awhile.

Minimalist, monochromatic tableaus form a sterile, and yet timeless and monumental facade, behind which you don’t have to peek in order to grasp the essence of Leth’s deadpan shenanigans.

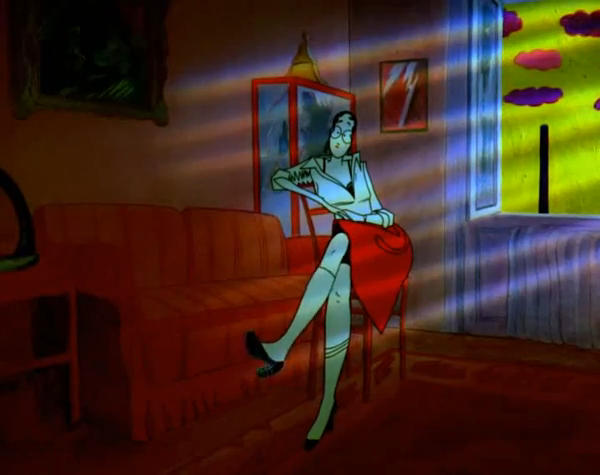

5. Foam Bath (György Kovásznai, 1979) – Hungary

Weirdness of the matrimonial kind

Kovásznai’s first and only feature follows dozens of shorts, in which he used combined techniques, driven by the principle of “uncompromising tolerance of plurality and simultaneity of -isms”. Foam Bath (Habfürdő), a farcical rom-com musical, clearly reflects the eclecticism of his style. It focuses on a love triangle among a geriatric nurse and doctor-wannabe Anikó, her colleague (and Cruelle de Vil double) Klári and Klári’s fiance Zsolt, who’s a window dresser.

In a simple story, marriage is rendered as an obstacle to dreams coming true – between the lines, there’s a commentary on the society behind the Iron Curtain. An awkward situation, brought forth by Zsoltan’s fear of bonding and in-laws, is depicted through the wild and daring experimentation with shapes, colors and textures.

Demonstrating the power of a drawing, Kovásznai deforms and transforms his characters in unimaginable ways – they pass through the phases of cubism, fauvism, surrealism, pop-art and geometric abstraction, yet they stay recognizable. Equally hybrid is the wryly humorous score, which contains the songs about blood circulation, bacteria and DNA (not to mention Zsoltan’s “techno deco” and “psychophoto deco” acts). Weird as hell.

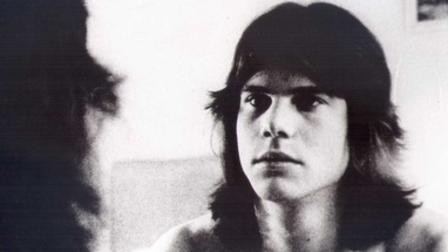

6. Taking Tiger Mountain (Tom Huckabee & Kent Smith, 1983) – UK/USA

Weirdness of the production hell kind

The history of TTM’s conception is as perplexed and interesting as the unconventional narrative. It involves Morroco arrest, a bitter quarrel in Spain, the townsfolk from the south of Wales, an “offensive” poem for William Burroughs and a ten-hour footage sold for a dollar.

The story takes place in a near future and it focuses on Billy Hampton, a Texan who flees from occupied America to British island in order to avoid compulsory military service. Once there, he’s abducted by a group of sophisticated feminist terrorists, who oppose the prostitution legalization and create assassins by brainwashing…

What follows could be described as a sporadically wet psychotropic nightmare, with hypnotic soundtrack composed of gloomy drones, overdubbed dialogues, confusing monologues and omnipresent radio announcements about the war aftermath. Along the harrowing reports and overexposed photography, even the most trite scenes, such as walking down the street or visiting the pubs, look like a paranoid hallucination. Oh, and the film stars then-anonymous and barely of age Bill Paxton.