It didn’t take long for cinema to discover the power of music, and the possibility of a crucial cinematic moment taking the emotional factor to ecstatic levels, through the use of a musical piece.

Many times, when a film needs to disclose an emotion that has been carefully built through various sequences, but needs to tap into a feeling, or a concept, or an idea that is not graspable through the screenplay or the mise en scene, a song will be used to work with the images in constructing elevating sequences that take the spectator off their seat and into a new stratosphere.

It’s this sensation, this feeling of elevation (to steal from Haidt) of achieving a superior emotional state, this almost ecstatic state of a glorified moment in time, that creates the metaphysical suspension that takes the film from a cerebral to a viscerally emotional level, that separates one sequence from the constant obligatory progression of scenes of the film and lets it shine as one single brightening mirage, a sonic and visual coronation, an illumination.

The real power of music is the power of catharsis, of breaking the constraints, of unlocking the raw submerged emotions of the spectator and the film that are hidden and barely visible, and can explode in all their uncontrolled flames. Music and film, catharsis and purification, the capacity of losing oneself in one single moment of life, unchained and free flowing.

1. A Spell to Ward Off the Darkness (Ben Russell and Ben Rivers, 2013)

Speaking of catharsis, the most purifying genre in modern music in considered to be black metal. The idea of isolation, of re-discovering the special connection between man and the forest, of freeing the demons and the evil spirits that inhabit the human soul.

The main character of the film silently wanders through Estonia and Finland, first in a commune, then completely isolated in a forest. He separates himself more and more from society, searching for something inside of him, a continuous initiation, a process of soul-searching, of getting in touch with the purity of existence, until he is ready for purification.

And then liberation happens, in evocative fashion. First we see a wooden house burning in the darkness, the fire illuminating the pitch black air, then, again, with the background completely black, we see our character.

He has white makeup on his face and he’s white as a ghost, white as a good spirit that has been cleansed and is now fighting against the darkness, and he sings with fury and beauty while a cascade of black metal sounds and a sonic vortex whirls around him, embracing him in his newfound condition.

Angelic pain and demonic rage are combined in the decisive battle for the human soul that happens in musical form. The sequence is both an exorcism and a celebration, the culminating moment of the film and of the formation of the self on screen.

2. Fucking Amal (Lukas Moodysson, 1998)

Sometimes you can find out who you are in a few seconds; maybe at night, maybe in the backseat of some stranger’s car. Lukas Moodysson’s film is about two young girls who discover love in a small town in Sweden, where their homosexuality is not looked upon with sympathy.

The cold, dark, wintry feel of Sweden also infects the two characters, who feel uneasy, contracted, and can’t really cope with the feelings they are experiencing and are out of the ordinary.

Maybe it’s a lack of courage, or maybe they just don’t know what they feel, but everything changes in a few seconds, and this liberating feeling of self-realization and discovery of love explodes in a brief sequence.

The two girls have difficult backgrounds; they are depressive, even suicidal, and they feel trapped by their problems just like they feel trapped in Amal, but one night they decide to hitchhike to Stockholm, and manage to get in the car of a total stranger.

The renewed sense of freedom, the idea of the great city, of an adventure, of infinite possibilities, allows their feelings to come out, and they kiss, first hesitantly, then passionately, while a cheesy power ballad from the 80s plays in the background.

It’s cheesy, but also honest, representing the ingenuousness and spontaneity of young love, with a warm embrace in the middle of the coldness of Sweden. The song is by the British band Foreigner, sang by Mick Jones: “I want to know what love is… I want you to show me.”

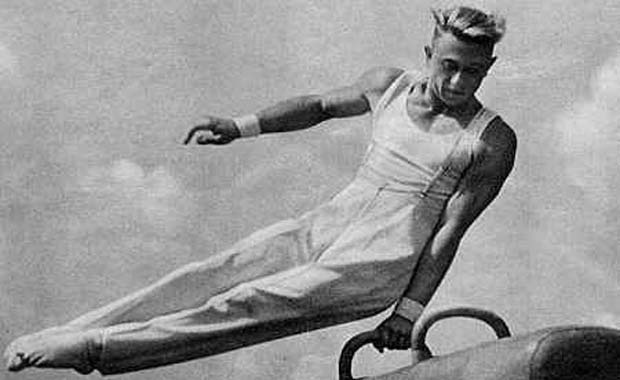

3. Olympia (Leni Riefenstahl, 1938)

The Festival of Beauty, the celebration of the best specimen of the human race, of strength, ability, intelligence, perseverance, is everything the Olympics ever stood for.

Leni Riefenstahl captured it in one of the greatest documentaries of all time, with dollies, pans, deep focus cameras, and other techniques that were absolutely visionary and are still a point of reference in covering sports events.

The sentiment of triumph, elevation, and the perfection of the human form has to be conveyed not just through images, but also true sounds. The soundtrack for the film is currently lost, but was crucial in the development of the film.

The sounds are the sounds of classical music, not as intense as the sounds of Wagner, but with an equal measure of solemnity and joyful marches. The great galloping sounds of violins and trumpets create a sense of an individual push for perfection, but also of a body at the peak of its power and efficiency.

Despite the obvious political implications, the film is a celebration of the human race, a concerto of images and sounds that elevate humanity from its terrestrial state to a divine one.

4. The New World (Terrence Malick, 2005)

It would be easy to pick any of the musical sequences in Terrence Malick’s films; for example, the majestic creation sequences in “The Tree of Life”.

The opening of “The New World” is a magnificent elegy, an epic poem about the waters, the heavens, and the earth. Malick’s camera starts in the deep blue waters and gently rises to envision the sinuosity of the human body, swimming naturally in the water, unseparated, united, a symbiosis that can only be found in the tribal state of human existence.

Wagner’s music is gentle and incredibly avant-garde, and considering the period in which it was composed, it sounds similar to a Popol Vuh soundtrack from an Herzog film (which is incredible considering the temporal distance).

It is music that is celestial in essence, it is the prelude to the tetralogy of the Ring, music about surging from the depths of the river to the accumulated joys of love and angelic beauty.

The vessels that caress the water represent, in a brief sequence, not a clash of civilizations (a predominant narrative in colonial films), but the conquerors of the New World as the natural continuation of the natives swimming into the ocean.

Malick shoots an incredible tribute to humanity and the wonder that lies in our special relationship with nature, a relationship of symbiosis, rivalry, and spirituality.

5. Two Days, One Night (Dardenne brothers, 2014)

“I’m a mess again.” This is one of the first things Marion Cotillard’s character says in this highly emotional and minimal drama by the great Belgian filmmakers, the Dardenne brothers.

Among the social commentary that the film provides, the terrible ghost that haunts the entire story is the one of depression, a depression that affects the female protagonist as she drags herself throughout the film, trying to fight this seemingly pointless fight to save her job and having to deal with a number of moral implications.

The camera doesn’t let her breathe, and the lyrical cinematic explosions are often very scarce; everything is very subdued, very intimate.

In the course of the film, in two key sequences, pop music offers a brief escape from the dire situation, and it perfectly captures the feeling of the sun peeking through the clouds, a brief moment of looseness where your tongue is freed and the heart stops aching and launches itself into a wild ride before settling down, and for a moment, the mind is clear from the mist and can see clearly.

6. Francofonia (Aleksandr Sokurov, 2015)

The subject of the film is the relationship between art and power, and Aleksandr Sokurov explores it with a style that mixes documentary and surrealism.

As we go through the Louvre, historical and mythological figures appear, while in the meantime a Skype conversation happens, and a French intellectual and a Nazi general talk, with a voiceover from the director himself that takes the liberty to speak with them.

Sokurov’s cinema has much in common with great painters, and it’s also cold in its appearance, sometimes locked in a series of intertwined cultural and philosophical references that make the content harder to grasp.

So, when the screen goes black and the film should be over, it is extremely surprising to see Sokurov abandon himself to lyrical, maybe even patriotic moments, as he is a firm opponent of any regime on Earth.

All of a sudden, the screen goes from black to red, and we hear the Russian anthem in a strange, detached, fragmented version, almost as if Sokurov is afraid of singing it. But we know what it means; it is the director’s desperate cry for freedom, which was the original meaning of the anthem, when it was sung by the working classes hungry for liberation.

It then became a symbol of oppression during the Communist era, and then a controversial symbol for new freedoms and new limitations. Throughout the anthem, Sokurov breathes freedom, as his lungs struggle to feel it and look for anything that could provide an escape, maybe, music itself.

7. Inside Llewyn Davis (Coen brothers, 2013)

How can I describe the last musical sequence in this film? Maybe with the words of Jon Kalman Stefansson, Icelandic poet and novelist, who wrote that the poet can’t push himself where his poetry gets.

It is the same with Llewyn; he is lost, broken, tired, lonely, and so he sings a heart-wrenching folk song of immeasurable nostalgia. “If I had wings, like Noah’s dove, I’d fly up the river, to the one I love.” But he doesn’t have wings, he only has his voice and the fire in his heart.

The Coen brothers reach the pinnacle of their lyricism in this sequence, which concentrates all the themes of folk music, the longing of the lonely man, the love for America’s wilderness, the ultimate futility of the American dream, the reality of poverty, the reality about how who’s pure at heart is bound to fail, and the power of music.

What’s left to do, when you’re a loser and you’re down and out? The only answer is singing a tender song of farewell, throwing our soul into the world before the memory of us disappears: “Fare thee well, oh honey, fare thee well.”