There’s a certain underlying derisiveness in calling a movie a “tearjerker”; the term suggests excessive sentimentality and manufactured emotion, a movie carefully designed to get viewers to bawl their eyes out.

A tearjerker can double as a genuinely great film though when that emotion is earned, and these ten films surely put in the work to earn your precious tears.

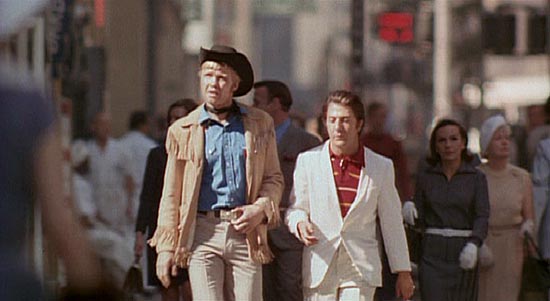

1. Midnight Cowboy (1969, John Schlesinger)

Out of all the sad movies out there, Midnight Cowboy stands out as something different and exceptional. It’s not so easy to pinpoint which aspect of the movie elevates it to masterpiece status – it could be John Schlesinger’s offbeat direction, the subtly brilliant script, Jon Voight and Dustin Hoffman’s indescribably moving performances, or a winning combination of all these factors – but there’s something about the film that makes it truly extraordinary.

Voight’s breakthrough role as Joe Buck is easily his best, a sensitive and deeply compassionate portrayal of a naïve man doomed to fail in his pursuit of the American dream. Buck, a bright-eyed Texan dishwasher with greater ambitions, takes a greyhound to New York City in hopes of becoming a successful hustler (read: gigolo), all while decked out in full cowboy attire.

The city, naturally, proves far more formidable than he expected and he experiences little success. He learns to rely on a new friend, Ratso Rizzo (Hoffman), a crippled con man who, like Joe, is treated like an outsider in the city. The two men are able to bond over their mutual feelings of loneliness and alienation as they work together to survive in the modern world.

There’s a lot to take away from the film; it’s as much a critique of capitalism and the American dream as it is a heartbreaking dissection of loneliness. Regardless of what it’s exploring at any given moment, the film has a raw, brutally honest power to it that acts as something like an emotional bulldozer.

Calling it a “sad movie” is far too reductive for something as profound as this; Midnight Cowboy truly has a life-changing sort of effect to it, a weighty aura that continues to simultaneously break the hearts and open the eyes of curious teenage film lovers discovering it for the first time.

It’s the kind of movie that reminds one of the power of movies and of art’s ability to affect us in ways we didn’t think possible. There is no other movie as devastating, as tender, as insightful and tortured and mournful and heartrendingly human as Midnight Cowboy.

2. My Own Private Idaho (1991, Gus Van Sant)

River Phoenix’s tragic death two years after the release of this film has certainly made it more high-profile as the most essential film of his career, but My Own Private Idaho is a stunner in and out of the context of Phoenix’s life.

Not far removed from Midnight Cowboy before it – a film with remarkable similarities to Van Sant’s both in terms of narrative and themes – the film tells the stories of two male prostitutes, Mike and Scott (Phoenix and Keanu Reeves respectively), getting by on the fringes of society. Mike, a narcoleptic drifter in search of a home, recruits Scott, the privileged rich boy rebelling against his politician father, to travel the country and eventually the world with him in search of his estranged mother.

There’s also a little bit of Shakespeare thrown in the mix, as Scott’s story is a (very) loose adaptation of Henry IV and some of the dialogue is lifted directly from the play, but that’s probably the least successful noteworthy aspect of the film.

What is worth noting, however, is River Phoenix’s hypnotic, impossibly compelling presence on screen. Evoking some definite East of Eden James Dean vibes, Phoenix gives a delicate, sensitive performance as one of the great tragic film characters of the 1990s. It’s his performance that lingers in the brain and haunts you long after the credits roll.

The film puts the viewer in the shoes of Mike in the way it drifts along at a dreamy slow crawl, with Phoenix’s narration bookending it like a bizarre fever dream. There’s a thick air of melancholy lurking just below the surface of just about every scene, but the ultimate takeaway is one of incredible beauty rather than just pure sadness.

River Phoenix didn’t live long enough to star in many more films as deeply felt as this one, but leaving behind something as special as My Own Private Idaho is accomplishment enough to solidify his legacy as one of the most extraordinary talents of his generation.

3. Paris, Texas (1984, Wim Wenders)

It’s a little surprising that a New German Cinema director would be the person to direct one of the most quintessentially American movies of the 1980s, yet here we are.

Wim Wenders’ Paris, Texas is uniquely American in its panoramic shots of Texan landscapes that evoke classic westerns and its cross-country road trip of a narrative, yet it’s not quite another Easy Rider or, dare I say, Rocky IV. This is America as a concept rather than a place: a country of cheap motels, neon signs, and vast desert vistas filtered through the eyes of an idealistic outsider who’s only previously experienced it via cinema.

What’s far more remarkable than its American-ness, though, is that Wenders is able to situate such an incredibly intimate and personal story against this broad canvas of Americana.

Harry Dean Stanton delivers the most poignant performance of his career as Travis, a man who wanders out of the Texas desert mute and amnesia-stricken after four years away from home. After his brother Walt (Dean Stockwell) locates him and flies in from Los Angeles to pick him up, Travis is forced to reconcile with the family he left behind and eventually confront the reason he left in the first place.

It’s an understated film to be sure, but that doesn’t make it any less than awe-inspiring. The gorgeous cinematography by Wenders’ go-to cameraman Robby Müller is jaw-droppingly beautiful and otherworldly – Texas is made to look like a barren alien landscape and the neon-lit cities evoke decades-worth of sci-fi imagery – and the script, penned by actor/playwright Sam Shepard and Texas Chainsaw Massacre 2 screenwriter L.M. Kit Carson (yes, really), is nothing short of flawless.

Every aspect of the film works in perfect synchronicity as it builds towards its inevitable, deeply melancholy conclusion. That ultimate narrative destination hardly elicits warm and fuzzy feelings, but it’s satisfying in a tough-but-fair sense and the film’s final stretch features a pair of the most painful yet moving scenes ever set to film in, of all places, a peep show club.

4. Au Hasard Balthazar (1966, Robert Bresson)

Boasting an unconventional filmmaking style that blends intense minimalism and profound spirituality, Robert Bresson is ranked among the greatest French filmmakers of all-time. While none of his films are particularly cheerful or light, Au Hasard Balthazar stands as an outlier in just how devastatingly sad it is.

The film is so bleak, so brutally real, so inconsiderate of its viewers’ emotional state that it’s genuinely difficult to watch at times, but putting in the effort to watch it reaps rewards: this is as harsh and powerful as film gets.

Future Godard muse/wife Anne Wiazemsky debuts as Marie, a young farm girl who is deeply attached to her donkey Balthazar. As Marie and Balthazar get older, the two are separated and they live parallel lives apart from each other; Balthazar is passed from owner to owner, withstanding incredible cruelty and neglect, while Marie is similarly degraded and mistreated by others time after time. While Marie struggles to handle the cruelty of the world around her, Balthazar perseveres through it all and bears the suffering with strength and nobility (surprise: it’s a Jesus metaphor).

In typical Bressonian fashion, nearly all the actors are non-professional. Bresson saw actors as directorial tools or models rather than as artists themselves, and thus in Balthazar he makes use of his infamous technique in which he breaks his actors down by filming take after take after take until their performances are raw and almost entirely drained of emotion. Despite this – or perhaps because of this – Anne Wiazemsky’s pained performance is incredibly powerful and imbues the film with much of its emotional weight.

Of course, the rest of the emotion comes from watching her donkey Balthazar as he suffers ceaselessly at the hands of his various owners. Because of its unflinching depiction of Balthazar’s abuse, this is never an easy film for an animal lover to watch. That being said, for those who can persevere through the discomfort of watching Marie and Balthazar be victimized by the world at large, Au Hasard Balthazar is a truly haunting, singular masterpiece.

5. Millennium Actress (2001, Satoshi Kon)

Along with the slightly more famous Hayao Miyazaki, the late Satoshi Kon was arguably the most important Japanese animator of the last 30 years. His films were vividly imaginative as well as hugely influential – American films as diverse as Inception, Black Swan, and Requiem for a Dream are all clearly indebted to his work.

While none of his films stand out as a clear “best,” Millennium Actress takes the cake in terms of the most emotionally draining. Beginning with a documentary crew visiting the home of a reclusive retired actress to interview her about her life, the film blurs the line between fact and fiction as events from her past become confused with scenes from her films.

Elements of her films are seamlessly interwoven into episodes from her life, making the boundary between real and false memories impossible to distinguish.

The film is in essence a love letter to film and the power it holds over our lives, but the incredibly personal approach it takes is what puts it on this list. Embedded in the actress’ life is a surprisingly affecting love story and a variety of Sliding Door-type “what if?” situations that make it incredibly poignant, and all the pent-up emotions eventually come to a hugely dramatic head in a mesmerizing and wildly clever final sequence.

The ending doesn’t leave you feeling happy so much as it does rip apart your heart into a thousand tiny pieces. Set aside some recovery time afterwards; you’ll need it.