Writing a script for the screen is no simple task despite the various hints, tips and formulas which circulate. There are no ‘rules’ or guarantees to success but there are many key factors to consider. It is always useful for the screenwriter to be able to dissect and analyse just what makes a particular film or indeed scene or sequence of scenes work effectively.

The following is a list of films (in no particular order of importance) all containing a scene or sequence(s) by which the screenwriter can learn something. Worth noting here is that this list ranges from the fundamental basics such as the ‘show don’t tell’ ‘rule’ to more subtle observations. Here are ten films with moments highlighting important aspects of scriptwriting for the screen:

1. Rear Window (1954)

One can consider the first rule of screenwriting to be ‘show don’t tell’. However, when struggling through a first draft the above phrase can sometimes be far easier said than done. Typically, problems occur in the early stages of a script as the writer struggles with just how to get all the required back-story (exposition) across to the audience without the script turning into a tedious dialogue about a central character’s life.

In Rear Window’s opening scene, Hitchcock, with his grounding the silent film era, offers the writer a lesson in just how simple visual exposition can be. The film, scripted by frequent Hitchcock collaborator John Michael Hayes, opens with the view from photographer L. B. “Jeff” Jefferies’ (James Stewart) rear window.

As the camera drifts into his room the audience can see the cast on his leg, with his name on it – they know who he is. Sweat on his brow and a shot of a wall thermometer info the viewer just how hot the weather is. Importantly here, the audience also see the smashed remains of a camera and a picture of a racing car hurtling to pieces (clearly toward the photographer) – straight away they know how Jeff came to have a broken leg.

However, there is more, the audience know that he is no amateur photographer as they see a stack of magazines, the cover shot in negative framed on his wall – indicating some professional success.

All this passes by relatively quickly, before a word has been spoken, leaving the viewer with a fairly good idea of who Jeff is and also (important for the plot) the limitations his current physical state imposes on his literal view of the world immediately outside. The camera and the shot of the car also project something of a taste of the dry humour into the proceedings, broadening the tone of the film a little.

2. Oliver Twist (1948)

Violence, how much is too much and just how far should the screenwriter go? This all depends on the context/gene of the film. However, as Alfred Hitchcock pointed out there is no lasting terror in the bang –only the anticipation of it. On a similar train of thought, getting the emotional and sensory impact of violent deeds across to the audience is what counts.

David Lean’s adaption of Oliver Twist (co-written with Stanley Hayes) scores on both the above points by bringing sound into the equation as a drunken Bill Sykes (Robert Newton) murders Nancy (Lean’s then wife Kay Walsh) by clubbing her to death. Here it is not the sight or sound of the actual violent deed, the shot cuts away quickly, which carries the impact but the piercing fanatic howling of Sykes’ dog Bullseye scratching at the door as it tries to escape the room which fills the audience with unease.

Unable to feel the physical pain a character may suffer, the screenwriter must make use of the audience’s other senses to heighten impact and aid understanding. Given the right signifiers, the audience’s imagination will visualise its own terrors. There is some argument here for the dog’s reactions passing aural and visual comment on Sykes’ own tormented ‘animalistic’ psychological state.

Here also, they arrive late – leave early rule of scriptwriting is observed as Lean cuts with sharp contrast from Bullseye to the following scene, a peaceful overhead view of the grimy streets the next morning – allowing the audience to breath and, along with Sykes, come to terms with what has just occurred.

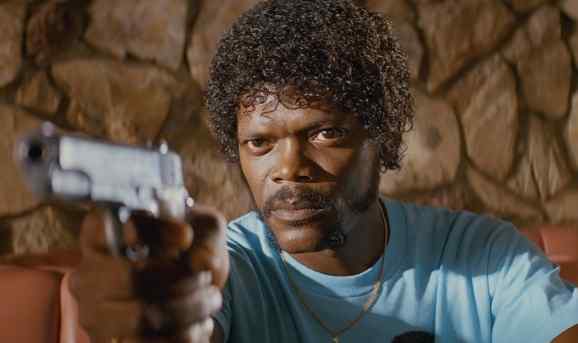

3. Pulp Fiction (1994)

Tarantino’s slick approach to dialogue has been commented on seemingly from the start of his career. The lesson here is that his approach is not a ‘dark art’ one may or may not be able to master.

Tarantino is falling back on the Shakespearian method and adopting iambic pentameter. Explained simply this allows for a rhythmic approach to sentence structure making use of syllables – ‘da dum – da dum – da dum’. This makes the dialogue at once catchy, memorable and perhaps less obviously artificial – ‘to be or not to be…’, or the equally repeatable ‘Roy-ale with Cheese’.

In Pulp Fiction (from an original story co-written with Roger Avery) the opening banter between Vince Vega (John Travolta) and Jules Winnifred (Samuel L. Jackson) it allows the for lengthier dialogue scenes to be snappier and less drawn out as the audience are drawn into the conversation.

In screenwriting terms this technique prevents an audience from becoming bored by adding rhythmic colour/texture to longer dialogue scenes – especially those of the expositional kind reeling off of back-story – the latter being a ‘must not’ of screenplays. Iambic pentameter as used by Tarantino is perhaps not an exact method, examples of it can be found in any of the writer/director’s own films.

Tarantino himself makes much of it in the extra features to his own Rolling Thunder Pictures DVD release of Jack Hill’s 1975 film Switchblade Sisters (aka Jezebels) – pointing out how an awareness and mastery of it can be also used to make dialogue sound bad purposely. Granted, iambic pentameter may suit Tarantino’s ‘film savvy’ stylistic approach and not every screenplay but an awareness of it in terms of pace and rhythm is a useful knowledge for the scriptwriter to have should dialogue difficulties surface.

4. Happy Go Lucky (2008)

In what is perhaps complete contrast to the ‘Tarantino approach’ to dialogue, director and scriptwriter Mike Leigh favours a far more genuinely naturalistic sound. The amount of scripting which goes into any Leigh film seems a matter of debate. However, he generally adopts the approach of developing character with the actors, giving them a general idea/plan of how a scene will play out and allowing the dialogue to flow naturally as it would happen in real life.

The effect, as in many of the driving lesson scenes within Happy Go Lucky, is one of miscommunication, awkward pauses, unfinished half sentences and slightly overlong beats between speech. Whilst Leigh himself might not script this, a screenwriter’s awareness of how this ‘real life’ dialogue sounds is a useful way of avoiding the overlong ‘perfect’ sentence construction which hinders the flow of a screenplay and worse still sounds very strained on screen.

One scene in H.G.L in particular, has Poppy (Sally Hawkins) cut dead in mid conversation as her driving instructor (Eddy Marsden) bluntly replies ‘My Dad’s dead.’ Before the conversation leads him to miss-conclude via a series of half spoken questions that Poppy lives with her lesbian partner of ten years. The scene jumps, starts, stalls and conveys all the genuine awkwardness of such a conversation perfectly.

5. Mad Max 2 aka The Road Warrior (1981)

Creating the all important audience empathy so that they will follow the ups, downs and plot twists a central character may experience can be make or break to a script’s/film’s success. In the instance of a straight forward clean cut or even lovable ‘underdog’ character this can be quite a straight forward issue to consider, some classic tricks could be liked by young children and/or animals, helps those in need and is popular with other characters.

It is also important that a character carries and conveys sufficient depth to maintain this audience interest. However, in a violent post-apocalyptic action movie world where even the good guys are forced to survive, this can prove a problem for the screenwriter.

Director George Miller’s Mad Max 2 (co-scripted with Terry Hayes and Brian Hannant – also released as The Road Warrior in the U.S) compounds this problem slightly with the added issue of the central character Max (Mel Gibson) being a lone protagonist throughout the opening sequence, this limits the potential for the audience to hear his inner thoughts (conveying depth and ‘motivation’) by simply voicing them. Even around others his speech is limited to the functional.

The film opens with a narration sequence, filling in backstory and ‘recapping’ the events of the pervious film – this may set the scene and inform us about Max and his tragic past but on its own a compelling ‘empathic’ character it does not permit – an audience need to witness and feel this.

The action sequence which follows the opening narration reveals Max to be quick witted and possess skill as a driver – an action hero but still an audience need more to stick with him for the duration of a feature film. Classic ploys toward audience empathy do occur – he owns a loyal dog. However, it is the quieter moments immediately after this opening action sequence which cement the audience’s union with Max when after he opens the door of the abandoned tanker and retrieves a tiny music box.

Crucially he not only studies it but winds it up, listens to the tune (almost smiling) and keeps it. For the audience this contrasts him against the gang of scavengers we have just seen, it is unlikely they would react in this way, Informing the audience that there is something more (something more mysterious) to the character than the simply functional (kill or be killed).

Most importantly the audience share this screen moment with Max – a secret – enabling them to form a strong empathic bond with the character. One may like to consider this as a ‘quiet moment’ – a break in plot and pace to allow the audience some screen time alone to bond with a character.