There are works of art that not only capture their moment but also change the language of the art itself. Fellini’s 1964 masterpiece, 8 ½ is one of these. When it was released in Italy, it received mixed reviews and was seen by many as Fellini’s further betrayal of his neorealist roots and the Neorealist movement (after La Dolce Vita).

All this changed when the film was released in the United States where it met critical acclaim, audience enthusiasm and resulted in a renewed interest in the way films told stories, in the way they created meaning and, in fact, lead to new stories to tell and new subjects to consider visually.

It is important to note that 8 ½ was produced after Alan Resnais Last Year at Marienbad – another ground breaking film that surely influenced Fellini (though I have no documented evidence for this assertion). Both films deal with time and the mind. Both films deal with reality as an experience made of memory, wish and perception but do so in very different ways.

Considered by some to be autobiographical, 8 ½ is an evocation and exploration of the experiences of Guido Anselmi, a director who is creatively blocked and seems unable to finish the film he is working on. He wanders through a maze of fantasies, memories, and encounters – real and imagined – with people who depend on him, love him and even hate him until finally it appears that he kills himself.

In the end, however the suicide may be only another fantasy as the film ends with Guido in a circus ring directing a final scene filled with everyone we have met in the film as well as some we are meeting for the first time. They dance and Guido joins them. The film Guido cannot make is the film we have just watched.

This list is meant to include those films that are influenced by, inspired by or might be considered responses to Fellini’s great work or at least films that seem to me to be so. The list is by no means exhaustive nor is it in rank order. Please make your own list, if you like.

1. Stardust Memories (1980, Woody Allen)

This is the most obvious and undisguised parody/tribute to 8 ½ in the list. Woody is a filmmaker who has been invited for a tribute to his work at a small film festival. As the film unfolds, we are given glimpses of his love life, his works, as they are screened, his problems with fans and sycophants, his fears and his desires, his lovers lost or imagined, even creatures from outer space.

In the end we are made to understand that the choices he has made – creatively, emotionally and intellectually – have been driven entirely by his art but unlike Guido in 8 ½, this has left him in a kind isolation, content or at least accepting of the world he has chosen to live in and create. The homage is straightforward. Stardust Memories is shot in rich black and white. Both films begin with a dream.

In 8 ½, Guido is trapped in a traffic jam as his car begins to fill with smoke; in Stardust Memories, Woody is on a train when he sees a beautiful woman in another train. She blows him a kiss but he is trapped as well. According to Ralph Rosenblum, the editor of Annie Hall (and many of Allen’s films up to Interiors), much of the material for Stardust Memories had appeared in the original 2 ½ hour cut of Annie Hall and there are still Fellini like moments remaining in the release version of Annie Hall.

Most obvious is when, in the Coney Island section of Annie Hall, two young women seem to notice the camera and blow it a kiss – this action echoes the nun who when seeing the camera in 81/2 turns away in giggling embarrassment.

In both these cases, we are asked to wonder whether the camera is objective or subjective: are these images real or imagined or remembered or happening for the first time and to whom? Allen is less interested in the creative process than Fellini – his film is oddly less introspective and so avoids the pretentiousness that is always on the edge in Stardust Memories.

Clearly however, Fellini’s decision to draw no distinct lines between the real and the imagined, memory and the present gives Woody Allen the liberty to do the same and to somehow neither insult nor fully imitate the original.

2. All That Jazz (1979, Bob Fosse)

An exuberant tour de force of autobiography and cinematic form, this film borrows from Fellini’s in subject and approach with the added torment of open-heart surgery and death. Again we are brought into the creative life of a challenged genius: this time Joe Gideon (Roy Scheider) who, like Fosse, is a choreographer turned theater director turned filmmaker. He is lauded for his work and driven to consume stimulants at an astonishing degree, abusing his body and all his relationships in pursuit of his art.

Like Guido and Woody, he cannot resist women and we are also lead to accept that this behavior is a necessary condition for his creativity. Everyone around him loves and in some cases pities him. The film moves between past and present as if they are one and the same.

The worlds Gideon inhabit – theater, cinema, and life – mix with memory and a kind of objective reality outside Gideon’s experience (as in the coverage of the open heart surgery). We learn that Gideon is a perfectionist, an innovator and a self-destructive egoist.

The film language of 8 ½ is present with almost every scene change as Gideon’s world is brought to our eyes and ears. And in the end as we understand that the heart surgery is his and it has failed. All That Jazz has been an expansion – Fosse style – of the last moments of 8 ½ but one where death does end all that is.

3. Beyond The Sea (2004, Kevin Spacey)

In one of the supplements to the DVD of Beyond the Sea Kevin Spacey directly states his intention to draw from 81/2 but you don’t need his comments to tell you that. A “biography” of singer, Bobby Darin, the film’s debt to Fellini is obvious right from the casting to its structure.

If 8 ½ brings to question the nature of reality in its unexpected juxtapositions, Beyond the Sea starts out doing so within the frame as Spacey, certainly older than Darin was when he died, steps on screen and performs as the singer without once trying to look younger or even different. In the two minutes, we see Spacey (as Darin) walking through the kitchen of the Copa Cabana on his way to a performance and someone, in the background says, “Isn’t he too old to play this part?”

From that moment on, the film moves freely from stage to street to dream to memory and does so sometimes right in the middle of a musical number (ala Cabaret) with Spacey singing, dancing and delivering his sense of the singer. There is a young Bobby as well and while Guido’s young self stays in his own time, Darin’s is there to confront his older self or offer support in a song or just watch as a moment unfolds.

The levels of reality and fantasy in one sense may seem more obvious than in 8 ½ or All That Jazz but Spacey makes no apologies for the ways in which they are integrated into what could be just another performer biopic. Spacey knows his Darin and knows how films can tell stories and his decision to play the main role without concern for appearance makes for a tribute to Fellini and to Darin.

At the end, Spacey/Darrin stands alone in an empty cabaret singing an old Bob Hope song and expressing gratitude for living the life on an entertainer. Is this 8 ½ turned inside out or Spacey giving us himself devoid of character yet always in need of performance even once created by camera and editor?

4. The Discreet Charm of The Bourgeoisie (1972, Luis Bunuel)

A satire. A comedy. A comment. All of the above? Bunuel began 1929 working with Salvatore Dali on Un Chien Andalou – the film with the sliced eyeball. He never really stopped working nor did he leave his Marxist/Communist roots. All his films are – one way or another – attacks on the emptiness of capitalist life especially on those who are “liberated” through wealth or kept “innocent” through the corrupting forces of religion and materialism.

In 1950 he made a social realist film, Los Olvidados, about juvenile delinquency in Mexico. This film while highly realistic contains a dream sequence of such strong images that it is as powerful today as it was when released. The Discreet Charm of The Bourgeoisie may lack the image power of that film but in its premise and exposition, it presents a subtle kind of power that reaches right back to the earlier films.

The film tells of a group of upper middle class couples trying many times to get together for dinner or a party. With each attempt they are foiled either by unwanted intrusions or arguments but also by the inventive way Bunuel takes us into their dreams (all of which seem to be about frustrated attempts to meet) – each dream echoes and foretells the others.

Sometimes they are dreams within dreams and a character will awake to detail how he dreamt that another character dreamt of a third character who had a dream – and all these ‘nested’ dreams are so smoothly joined as to become one. We see the characters together at each attempt to meet but the sections of the film are linked by of shots of all or most of them walking down an empty road, determined but with no destination revealed.

These rural shots are spaced throughout the film and seem variations on the coming together at the conclusion of 8 ½. But if life is a circus for Fellini, it is an empty entertainment for Bunuel. The charm of these characters rises from their constant willingness to accept their state without question and to move through the world at a steady pace as if by doing so they will avoid the chaos and unpredictability of life whether it is dreamt or lived.

5. The Great Beauty (2013, Paolo Sorrentino)

In some ways this lovely film seems a subtext to 8 ½ although it is more often compared to Fellini’s earlier film, La Dolce Vita. This is certainly due to the way that The Great Beauty presents us with the hedonistic life style of upper class Rome but this representation is tempered with intersections with past time and moments of memory and fantasy.

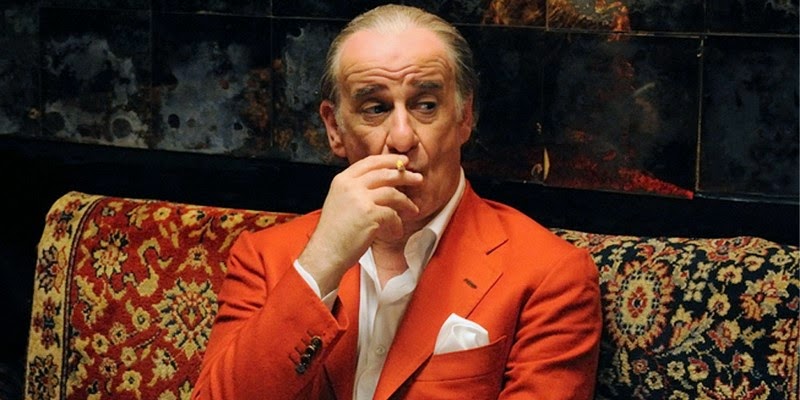

The Great Beauty tells the story of Jep Gambardella, a writer with one great book to his credit – a book written and published over 40 years ago. Since that time, Jep has written a kind of gossip column about the the rich and famous of Rome and now – as we meet him – on his 65th birthday he questions all that he has done – or rather not done – and what it was for.

Jep travels through Rome meeting people he knows or has known and many of these encounters take him to another time or another vision, to an experience wished for or had. Jep seems to be Guido at the other end of life – long after the circus has closed, still performing and still looking for meaning. His youth is shown in a series of sequences on the Italian coast where a group of young people plays and flirts with each other.

One of these – a girl slightly older than Jep – finally near the end of the film, reveals herself to him and there is good reason to believe that this is the great beauty of the title, not Rome or all its pleasures. This beauty is there and lost and so Jep’s confrontations with those he meets and those he remembers are only given context when we are brought to this moment. Jep has given in to his creative block even as Guido found release from his.

Each moment – from the opening and seemingly overdone party to the interactions with the mysterious (gangster?) neighbor to the Mother Theresa like nun who finds Flamingos on Jep’s terrace – each moment is representation and interpretation at the same instance. In 8 ½ Guido struggles to define a role for the beautiful Claudia Cardinale (“There is no film,: she tells him). In The Great Beauty, Jep struggles to find a place for himself and finally does in the beauty of a woman lost to him forever.