Today, animation is a profitable and influential industry. Due to the rise of CGI, it could be argued that most of today’s cinema is really animation. When the word “animation” is mentioned, most think either Disney or Japanese anime. But the rest of the world has a long and proud animated history as well.

It’s particularly true for the continent of Europe, where a diversity of cultures means that artistic visions can radically vary from country to country. Many factors contribute to this diversity, from the cultural traditions to political climate in a given country (state-sponsored artists of former Communist countries may enjoy more financial backing, but also have to deal with more government control, for example).

This is a list of animated features made in Europe from early 1920’s until now. The majority of entries here are non-CGI, as the personal techniques of drawing or stop-motion makes for more unique and rewarding works. Many of them will shock and disturb, but all are rewarding in their own way.

1. The Adventures of Prince Achmed (1926, Germany) Dir. by Lotte Reiniger

Heads the list as the oldest surviving animated feature in the world, and one of the first ever made. The double-tale of Prince Achmed and Aladdin battling mythical demons and finding love is presented in the silhouette, Chinese shadow play tradition.

Unlike the live shadow show, here the characters are animated frame-by-frame. Thankfully, the film was restored in the late 90’s with the original color tints-the changes from deep blue to menacing red to mysterious yellow further enhance the story.

It took the creative team three years to painstakingly make it, and it shows on screen. A 65 min. journey into a magical world. One of its makers, legendary German filmmaker Walter Ruttman, have often complained about the film’s lack of modern relevance. Seeing it now proves he was wrong.

Other works: Reiniger’s long career is marked by many shorts in similar style. Doctor Doolittle (1923), Papageno (1935), The Grashopper and the Ant (1954), Aucassin and Nicolette (1975)-all worth seeing.

Her team of collaborators on Prince Achmed included Walter Ruttman (famous for his abstract shorts and 1927’s Berlin: Symphony of a Great City) and Berthold Bartosch, a pioneer of serious and artistic animation who was way ahead of his time.

2. The Tale of the Fox (1937, France/Germany) Dir. by Ladislas Starevich

A French writer once said “No, I’m not going over to visit Starevich. I don’t want him to turn me to stone, or sic his gnomes, spirits, horrible flies and dragons with diamond eyes on me.” To contemporaries, Starevich’s stop-motion works were nothing short of magic.

For this adaptation of the medieval legend of sly foxes, regal lions, predatory wolves, and other anthropomorphic animals, he created intricate puppets, ranging from a few inches to human-size, as well as up to 500 masks for each of them, thus being able to make them come to live. Production and distribution problems delayed its release for 7 years, but once out it continues to amaze.

Other works: Starevich is stop-motion. In addition to this feature, the following shorts are not to be missed: Cameramen’s Revenge (1911), The Insects Christmas (1912), The Frogs Who Wanted a King (1922), Fetiche (1933). In addition, he made stunning live-action and science films.

3. The Humpbacked Horse (1947/1976, USSR) Dir. by Ivan Ivanov-Vano

Late 40’s to 50’s were, in Soviet animation, the era of rotoscope fairy tales. This was done to compete with Disney productions. While using many of the same aesthetics as Disney, the use of rotoscope enabled to overcome technical deficiencies. At their best, talented animators were able to create enchanted and magical worlds. Of them, Ivanov-Vano was arguably the best.

This 19th century poem-tale of a simple lad who undergoes trials and adventures, with the aid of his flying, magical, ingenious titular horse with a humpback and long ears, became a calling card of Soviet animation. By the 70’s, the original negatives were badly damaged, and as restoration technologies at the time were limited, the director simply remade it. Both the restored original and the remake remain engrossing and magical.

4. The Snow Maiden (1952, USSR) Dir. by Ivan Ivanov-Vano and Aleksandra Snezhno-Blotskaya

Ivanov-Vano gets the back-to-back listing because this tale is one of the most beautiful animated films ever made. Featuring some of the most stunning backgrounds ever animated, this rotoscope film is a loose adaptation of Rimsky-Korsakov’s opera bout the daughter of Frost and Spring who yearns for human warmth, with tragic results.

The use of luminescent paints make the whole endeavor literally sparkle and glow before the spectator’s eyes. At this late Stalinist time, Soviet animators were ordered to make tales such as these to compete with Disney influence. If only all of Cold War was spent in such competitions. Rotoscope method was called éclair in Soviet Union, and this films shows why-it’s sweet and delicious to look at.

Other works: Ivanov-Vano had a lasting influence on the world of animation. His works transcended ideology and influenced both Eastern European and Japanese animators.

From his groundbreaking early shorts China in Flames (1925), Ice Rink (1927), Black and White (1932), to the above-mentioned features and other like The Twelve Months (1956) and Lefty (1964), to his inventive late works Seasons (1969), The Battle of Kerzhenets (1970, with Yuri Norshteyn), and anti-war Ave Maria (1972)-the world of animation owes him a debt of gratitude.

5. The Animal Farm (1954, UK) Dir. by George Halas and Joy Batchelor

Britain broke into animation features with flair. This adaptation of George Orwell’s legendary dystopian parable was the first British animated feature ever made. In addition to being the start of the good tradition, it benefits from quality artwork while managing to stay mostly true to the original tale of the revolution on the farm.

It probably would be even more striking it was aimed at adults (the duckling interludes and the more hopeful ending do take away some visceral power), but it remains a successful adaptation and a good film in its own right.

6. The Snow Queen (1957, USSR) Dir. by Lev Atamanov

This holiday classic transcended ideology, language barriers, and two oceans. It won top prizes at Venice and Cannes. And, no less an animator than Hayao Miyazaki has admitted that it was a decisive influence on his choice of profession (he also recently released it in Japan). It is The Snow Queen, Lev Atamanov’s adaptation of Hans Christian Andersen’s fairy tale.

Andersen has been supplying animators of all countries with plentiful material. This may be one of his best-adapted tales. Made towards the end of the rotoscope era of Soviet Animation, its appeal is easy to see-it’s gorgeous to look at and heartwarming.

The story of the little boy Kay who is gets enchanted and taken by the ice-cold Snow Queen, and his friend Gerda who never stops searching for him, finds him, and thaws out his hoar frosted soul-with the help of several kind and magical creatures-it’s guaranteed emotional gold. The rotoscope technique in this case does not appear clunky or lifeless, thanks to the talented artistic team.

What must have impressed someone like Miyazaki the most is the perfect blend of form and content. The exquisite backgrounds, the non-intrusive and timely music (by Atamanov’s fellow Armenian and legendary classical/jazz composer Artemi Ayvazyan), colorful and perfectly-voiced characters-the list can go on. Of these characters, the titular one is the most memorable, with her icy beauty.

In general, Kay and Gerda get upstaged by a wonderful host of supporting characters, whether it’s the raven couple, Angel the tomboyish robber girl, or Ole Lukoye, a gnome of dreams from another Andersen tale that bookends this film. But the heart of Andersen’s story remains, and it’s at the right place.

Other works: Atamanov’s career spans almost 40 years. The 50’s were his golden period, with rotoscoped classics Yellow Stork (1950), The Scarlett Flower (1952), The Golden Antelope (1954). Of later works, Ballerina on the Boat (1969) is a beautiful and lyrical short.

7. A Deadly Invention (1957, Czechoslovakia) Dir. by Karel Zeman

Arguably the very first steampunk film, this is a one-of-a-kind work that influenced the likes of Terry Gilliam, Tim Burton, Jan Svankmajer, and Wes Anderson. Zeman came up with a wholly original stylistic idea of bringing the old illustrations to life via animation and combination with live actors, as any cinematic tricks available at the time-double exposure, miniatures, stop-motion.

The line engravings by Gustave Dore, Leon Bennet, and Edouard Riou are here toned, nuanced, and alive. Aided by an intricate musical score, this adaptation of Jule Verne’s Facing the Flag began its triumphant sailing around the world with a top prize at the 1958 World Expo, and continues to amaze and inspire.

Other works: the features not to be missed are Baron Munchausen (1961), a Jester’s Tale (1964) and Krabat-The Sorcerer’s Apprentice (1977). Zeman made a few unique shorts as well: Inspirace (1949), and the Pan Proukock (1947-1959) and Sinbad (1971-1974) series.

8. A Midsummer’s Night Dream (1959, Czechoslovakia) Dir. by Jiri Trnka

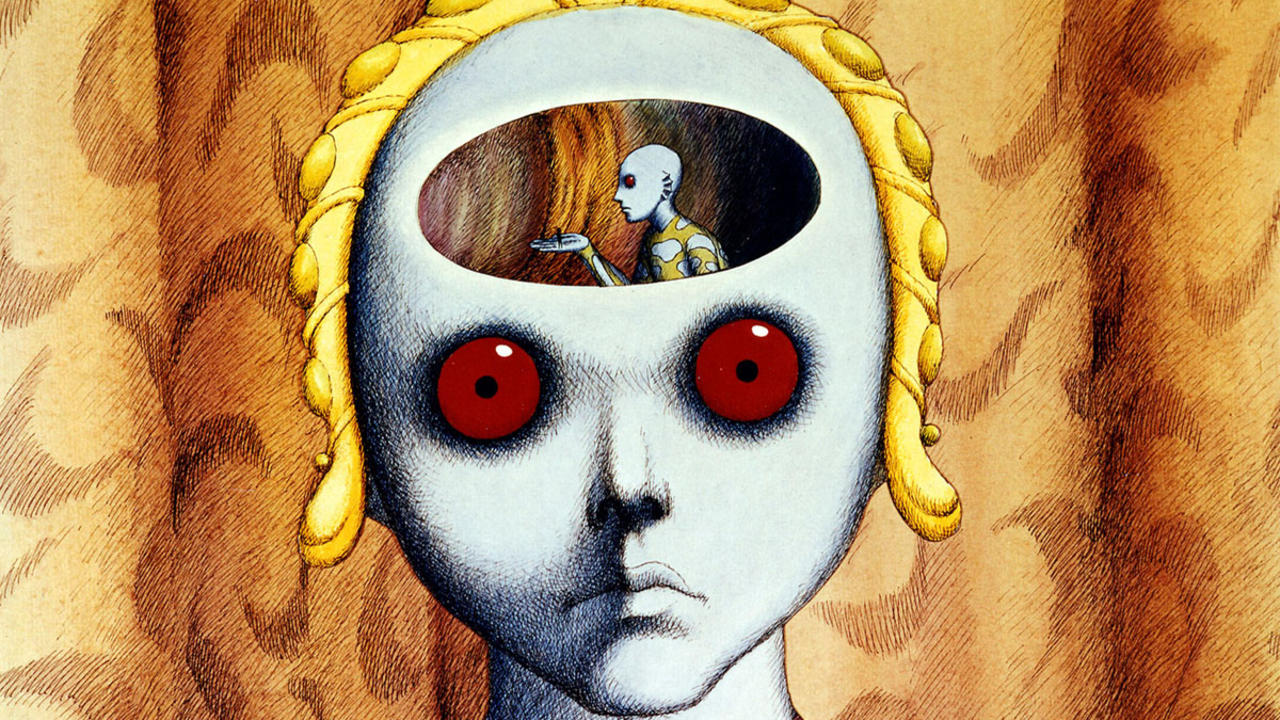

A monumental illustrator and puppeteer, Trnka was well-prepared to make this magical film, having created amazing illustrations for it earlier. Everything in the frame is hand-made by the artists, down to every painstaking detail.

The puppets have anime characteristics decades before anime-particularly, the eyes, which Trnka always made large and expressionless (that allowed him to change the mood of the character simply by adjusting the lighting or moving the camera). Oberon and Titania are magical, donkey-headed Bottom is touching and sympathetic, and Snug and Puck are appropriately entertaining. Trnka demonstrated to all that animation can be a unique art form.

Other works: take a pick, you will not be disappointed. Best features are Emperor’s Nightingale (1948), Prince Bayaya (1950), Old Czech Legends (1953), The Good Soldier Svejk (1955). Shorts not to be missed are Story of a Bass (1949), Western parody A Song of The Prairie (1949), the cut-out A Merry Circus (1951), and, especially, the darker political allegory The Hand (1965).

9. Wild Swans (1962, USSR) Dir. by Mikhail Tsekhanovsky

Hans Christian Andersen meets William Shakespeare. Considering the country of make, this Andersen adaptation is surprisingly gothic in look and feel. Made after the rotoscope method stopped being the dominant technique in Soviet animation, it features strikingly drawn medieval surroundings.

The story of a girl who must fight a curse both to win love and save her brothers (who were transformed into swans) perfectly captures Andersen’s bittersweet melancholy. The only deviation here is that in the atheistic USSR no mention could be made of Eliza’s piety (her saving grace in the story), but in this case it only adds to her character by making her naturally strong-spirited and resilient.

Other works: Tsekhanovsky was one of the first Soviet animators. His early works are striking in graphic detail-Post (1929, remade in 1965), Pacific 231 (1931). Later he had to switch to making films for children, but they too bear his talent for drawing an effective detail and creating the mood-Kashtanka (1952), the Spanish-inquisition tale The Legend of the Moor’s Testament (1959).

10. Adventures of Mowgli (1967-1971, USSR) Dir. by Roman Davydov

This “Jungle Book” adaptation couldn’t be more different from Disney’s. Made as five shorts over a four-year period, together they form a feature. It’s not a musical, and though it has plenty of comic relief moments, it’s not a comedy. The story of a human child lost in the jungle and raised by the wolves is presented here as a drama, or rather several dramas-coming of age, finding friends, fighting for life and freedom.

This affects the esthetics-Mowgli and most of the main characters are very realistic in look. They are finely drawn, and the backgrounds are stunning-the world of India wilderness is colorful and vibrant. The voicing is top-notch, so the main characters are memorable-gruff Balu, noble Akeela, wise and menacing python Caa (you really want him more as a friend than enemy), cruel and inhumane Sher Khan, cowardly jackal Tabaki.

One major deviation from the source novel and the film’s look is Bagheera. Here she is a female, and is drawn like a liquid mass of black ink. The panther’s feline qualities are intensified with this sex change-this Bagheera goes from languid and purring to fearless fighter in a split second.

The decision pays off-the character is given a new dimension, simultaneously creating a strong and positive female in the male-dominated world of the jungle. Special mention must be given to music. Sofia Gubaidullina is possibly the greatest living composer of today, and her challenging works continue to inspire memorable performances and recordings.

At the time, her mix of spiritual and avant-garde composition was out of favor in Soviet Union, so she had to make a living scoring films and cartoons. In this case, it’s animation’s gain-she gives each main character own musical themes (Bagheera’s mix of cello, violin, and keyboard is particularly effective) and creates an atmospheric and hypnotic overall musical tone. On all levels, this is a masterpiece.