21. Orson Welles

Before venturing into Film, Orson Welles had already been responsible for groundbreaking productions in Theater (Caesar, his 1937 Broadway adaption of Shakespeare’s play) and in radio (The War of the Worlds, perhaps the most famous radio broadcast ever).

At just 25 years old, Welles directed, starred and produced his very first feature-film: Citizen Kane. A flop at its original release, Kane has since become one of, if not the most highly regarded film of all time. Its ingenious cinematography and non-classical narrative style were pivotal to the development of what we now call modern filmmaking.

A progressive “auteur” in a knowingly contained environment, Welles creativity was restrained by the major studios. His films were commonly edited and many remained unfinished. He did manage to produce 13 features in his career and virtually all of them offer intriguing, if not always entertaining journeys. In Hollywood, besides Kane, he also made the brilliant The Magnificent Ambersons and the excellent Noirs The Stranger and The Lady from Shanghai.

22. Otto Preminger

Austrian filmmaker Otto Preminger arrived in the US in the 1930’s aiming to continue his stage directing career at Broadway. He worked in both stage and film until the 1944 release of his highly stylized Noir Laura, which was enormously successful and made him into a big Hollywood name.

Preminger went on to direct another esteemed mystery Fallen Angel, a remake of the Lubitsch silent Forbidden Paradise, retitled A Royal Scandal and the Joan Crawford vehicle Daisy Kenyon, which reunited Preminger with his Laura leading-man Dana Andrews.

In 1950’s and 1960’s, his work took a controversial turn, with several productions finding censorship trouble. In The Man with the Golden Arm, Preminger became one of the first Hollywood directors to address heroin addiction; four years later, the courtroom drama Anatomy of a Murder openly discussed a rape case and in 1962 homosexuality was the theme for Advise a & Consent.

A daring and accomplished director, Preminger made over 30 films and was twice nominated as Best Director at the Academy Awards.

23. Preston Sturges

The winner of the very first screenwriting Academy Award for his work in 1940’s The Great McGinty , Preston Sturges is often considered the first Hollywood writer to successfully transit to directing his own creations.

His work in screwball comedies was decisive for the genre, which was just coming into its own in the 1930’s. Sturge’s witty lines and naturalistic approach seems very modern today and film historians commonly point out his almost avant-garde impulse to break the classic narrative timeline in films like Unfaithfully Yours and The Miracle of Morgan’s Creek.

In a period of only four years, Sturges released his best remembered and most acclaimed comedies such as Christmas in July, The Lady Eve, Sullivan’s Travels and The Palm Beach Story. In 2000, four of his movies were chosen as part of AFI’s list of 100 funniest American pictures.

24. Raoul Walsh

An accomplished actor before he turned to directing, Raoul Walsh played John Wilkes Booth in 1915’s The Birth of a Nation, while at the same time, learning the trade from the very best, as an assistant director to D.W. Griffith.

In 1930, he noticed a young prop boy named Marion Morrison and chose him as the star for his Western The Big Trail. The director also famously found him a more star-suited name – John Wayne.

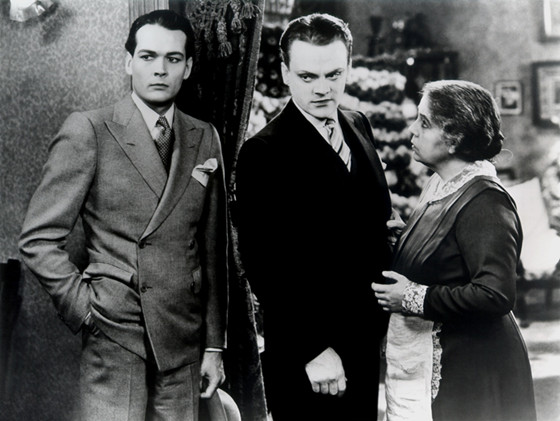

By the end of the decade, Walsh’s career took off in definite upon his move to Warner Brother’s. There he would gain fame primarily for his work in Crime films alongside WB’s toughest guys: Humphrey Bogart and James Cagney.

Among their greatest collaborations are High Sierra, The Roaring Twenties, They Drive by Night and White Heat. He also worked many times with swashbuckler star Errol Flynn, having directed him in a boxing flick (Gentleman Jim), a historical drama ( They Died with their Boots on ) and a war adventure ( Objective Burma). Walsh retired from Film in 1964.

25. Robert Wise

Robert Wise was a Film lover from a very early age. At 19 his dream of working in the industry came true as he was hired as a sound editor by RKO. By the late 1930’s he had drifted to editing film itself. Undoubtedly, his most famous work in that field was in Orson Welles’ Citizen Kane, for which he was nominated for an Oscar.

His directorial career came about while working for producer Val Lewton, when the original director of The Curse of the Cat People was taken off the production and Wise assumed his place.

An extremely versatile professional, Wise did not let his own personal style overlap the story’s formalistic demands. His craftsmanship led to major successes in a great variety of genres, from Sci-fi ( The day the Earth Stood Still and Star Trek) to musicals ( West Side Story and The Sound of Music) and from war dramas ( The Sand Pebbles) to a boxing-themed Noir ( The Set-Up), Wise mastered the very art of filmmaking in spite of the studio system’s creative drawbacks.

26. Stanley Kramer

As an independent producer/director Stanley Kramer had the autonomy to choose his own projects, an advantage not many of his colleagues enjoyed. He put it to good use, picking socially relevant topics that most studios didn’t dare approach.

With Sidney Poitier, Kramer addressed racism twice, first in 1958’s The Defiant Ones and then in 1967, in the last Katharine Hepburn/Spencer Tracy film, the dramatic comedy Guess Who’s Coming to Dinner.

He also bravely promoted a science x religion discussion in Inherit the Wind and reflected on the responsibility for the horrors of WWII, in what is perhaps his greatest accomplishment in filmmaking, 1961’s Judgment at Nuremberg. Although, best remembered as the director of the all-star comic adventure classic It’s a Mad, Mad, Mad, Mad World, Kramer undeniably left a consistent body of work that is still relevant today.

27. Victor Fleming

The man behind such mandatory classics as Gone with the Wind and The Wizard of Oz, arrived in Hollywood as a stuntman. Slowly, Victor Fleming transitioned to working behind the camera, and in 1916, he was one of D.W Griffith’s cameramen for his masterpiece Intolerance.

Silent Film superstar Douglas Fairbanks gave him the chance to start directing and, by 1933, Fleming had shot to stardom names like Clara Bow (with his 1926 film Mantrap), Gary Cooper (Fleming’s first sound production, The Virginian) and Clark Gable ( Red Dust, released in 1932, after Fleming’s successful move to MGM)

At his prime, Fleming was considered Metro’s most trustworthy director, an efficient professional who could bring order to the most difficult productions. Unfortunately, Fleming’s name has somehow lost its luster with time, having become encapsulated by the “factory” analogy we came to apply to the studio-system. Still, films such as Captains Courageous and Treasure Island reveal the unmistakable artistry of a filmmaking genius.

28. Vincente Minnelli

Born in 1903, in Chicago, Minnelli showed artistic flair as a young man and decided to become a costume and set designer for the Theater. His film-directing gift was not unveiled until the 1940’s while working at MGM.

Minnelli’s first sole assignment was in the 1943 Busby Berkeley musical A Cabin in the Sky, a daring project which featured only black actors. The genre would become the director’s specialty and he would go on to direct such classics as Meet Me in St. Louis, Gigi, The Band Wagon and An American in Paris. A perfectionist, who seemed greatly preoccupied with delivering harmonic aesthetics, Minnelli made visually stunning films which often featured glossy color cinematography.

Although the director also produced some remarkable work in drama (Home from the Hill, Lust for Life and The Bad and The Beautiful) and comedy (Father of the Bride and Designing Woman), his name will always be interlinked with Classic Hollywood’s best musicals.

29. William A. Wellman

“Wild Bill” Wellman was an aviation enthusiast who started in movies as an actor, but grew to hate his profession and so he moved to directing. He was known for his rough ways on set and many stars found it difficult to work with him. Still he managed to direct several actors into Oscar nominations, including Fredric March and Janet Gaynor for A Star is Born, a film which Wellman himself co-wrote.

Wellman was also the director of the very first Oscar winner for Best Picture, 1927’s Wings. Not likely to miss a chance at flying, he can be seen in the film as a German pilot.

During the Pre-Code days of Hollywood (1929-1934), Wellman had one of the most prolific stages of his career, directing such daring woman’s dramas as Night Nurse and social commentary films like Wild Boys of the Road. At that time, he was also responsible for the archetypal gangster film The Public Enemy.

Equally apt in comedies, like the satirical Nothing is Sacred, and Westerns, such as the The Ox-Bow Incident, Wellman’s talent was actually quite flexible and he showed a true artist’s sensibility despite his aggressive style.

30. William Wyler

A distant cousin of movie mogul Carl Laemmle, William Wyler started in pictures at Universal, when he was just 18 years old. Success and fame came in 1930’s when he formed a prestige partnership with producer Samuel Goldwyn.

Under Goldwyn’s contract, Wyler struggled for his creative freedom, but still managed to direct some of the best movies of his career. The first being 1936’s love-triangle drama These Three, with a story loosely based on the play The Children’s Hour – Wyler himself would remake the movie in 1961, keeping the original homosexual subplot, shunned at the time for censorship reasons.

The acclaimed marriage drama Dodsworth followed, alongside his first Best Director nomination at the Oscars; an award he would win for the first time in 1943, for Mrs. Miniver, which also took home the Best Movie award and a Best Actress one for Greer Garson. On that note, Wyler was a celebrated “women’s director” who gave Oscar wins to Audrey Hepburn, Olivia de Havilland and Bette Davis.

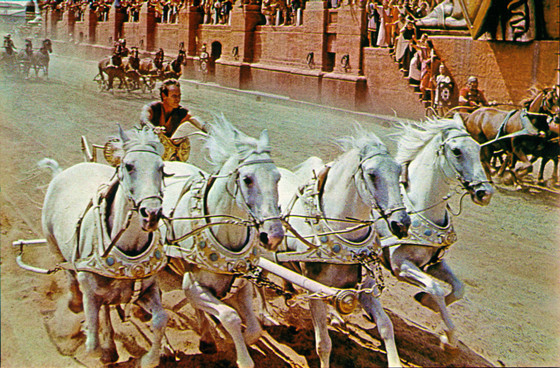

Wyler would eventually win two more directing Academy Awards, first for The Best Years of Our Lives, a touching account of WWII soldiers’ readjustment to civilian life and then, of course, for the all-time epic masterpiece Ben-Hur.

Author Bio: Priscilla Signorelli is a 23-year-old Brazilian Film Graduate. She’s obsessed with everything Classic Hollywood, but will gladly watch anything from Ingmar Bergman to Marvel movies. Her dream is to work as a Film Historian and share her passion for old movies with the world.