From the introduction of the sound age, in 1927, to the birth of New Hollywood, in 1967, Hollywood saw its prime, regularly producing films of high technical and entertainment quality.

The creative powers behind such masterpieces as Gone with the Wind, Citizen Kane and Double Indemnity were a distinct group of men. A good part of these filmmakers were European émigrés, who lent their talent to American films when their own national industries fell behind in the competition for world-wide control of the Industry; but many others were all-American types, who compensated an occasional lack of cinematic sophistication by telling straightforward stories with cleverness and skill.

Finally there are still those who simply don’t fit in any category; foreigners guided by the most American of values, like Frank Capra, and Americans with the greatest refinement of style like Orson Welles.

Notwithstanding their differences, all 30 directors of this list contributed with their particular talents to Hollywood History, helping to make The Golden Age the most iconic period of American Film.

Please note that this article is not a ranking and the filmmakers are listed in alphabetical order.

1. Alfred Hitchcock

Alfred Joseph was the youngest son of Emma and William Hitchcock, a traditional English couple, who gave him a strict Catholic upbringing. At 20, he began working as title card designer for a British branch of Famous Players-Lasky.

His first full-scale attempt at directing was in 1925’s The Pleasure Garden. Two years later, Hitch released the thriller The Lodger, a film that carries many elements that would become his trademarks, such as an innocent main character who is falsely accused of a crime and the first of the director’s famous cameo appearances.

The man responsible for Hitchcock’s Hollywood career was American producer David O. Selznick, who picked him to direct his 1940 adaptation of the novel Rebecca. The film would win as Best Picture at the Oscars and earn him a nod for directing.

Although Hitch received four other nominations as Best Director, for Lifeboat, Spellbound, Rear Window and Psycho and was also behind countless other classics such as The Birds and Vertigo, he would astonishingly never win a competitive award. But admittedly, no golden statue could ever be a greater prize than the title of “The Master of Suspense”.

2. Billy Wilder

An undisputed cinematic genius, Billy Wilder was born on June 22, 1906 in the now extinct Austria-Hungary, where he gave up a promising career as a lawyer to become reporter. Having been long fascinated by the theatrical world, he soon found himself amidst the entertainment industry, writing scripts for UFA, until Hitler’s rise to power made the Jewish Wilder flee the country.

After a quick stay at Paris, where he directed his first feature, Wilder went the Hollywood way and never looked back. His early years in the USA were marked by a successful screenwriting partnership with Charles Brackett, with whom; he collaborated with in such classics as Ninotchka and Ball of Fire.

The first American film he directed was 1942’s delightful romantic-comedy The Major and the Minor, followed by the war thriller Five Graves to Cairo and then by the all-time Film Noir classic Double Indemnity.

In his long and irreproachable career, Wilder would turn out such diverse masterpieces as The Lost Weekend, Sunset Blvd and Some Like it Hot; among many others, that have made him one of the most celebrated names of filmmaking History.

3. Cecil B. DeMille

Known for his high-value epic productions, Cecil B DeMille was a pioneer of the American Movie Industry. In 1913, alongside Jesse Lasky and Samuel Goldwyn, he created the Lasky Film Company, which would eventually become Paramount Pictures.

His first take on biblical tales was the silent The Ten Commandments (1923), which was just as critically and profitably successful as his better known 1956 film.

In the 30’s and 40’s, he took his showmanship talent to new levels with films like Cleopatra (1934), Samson and Delilah (1949) and the circus themed The Greatest Show on Earth, which won the Academy Award for Best Picture of 1952.

DeMille can be seen playing himself in Billy Wilder’s Sunset Blvd. In the film, he is credited with discovering and developing Norma Desmond’s talent; in real life, leading-lady Gloria Swanson also owned her career to the director.

4. Charlie Chaplin

One of the most recognizable faces of 20th century Entertainment, Charlie Chaplin was the first Film celebrity to attain incontestable world fame. Born to poverty in London, he performed in vaudeville since childhood. In 1910, he joined a troupe in an American tour and four years later The Little Tramp character was born under Mack Sennett’s direction.

In 1919, Chaplin, D.W. Griffith, Mary Pickford and Douglas Fairbanks founded United Artists, a distribution company which enabled them to control their own productions. In 1921, Chaplin released his first feature film, The Kid.

By the 1930’s, when sound had already dominated motion pictures, Chaplin was hesitant to adhere to the new technology and put out two more silent masterpieces: City Lights and Modern Times. When he did finally speak in film, in 1940’s Nazi-fascism satire The Great Dictator, Chaplin had a lot to say about the state of the world

His personal life was marked by scandal, including a paternity suit and accusations of communism. Nonetheless, his reputation as a Film icon deservingly only grows with time. Chaplin directed, wrote, acted and even composed the score of many of his pictures – He was a true genius of the craft of filmmaking who has become immortal thanks to the timeless optimistic outlook of his work.

5. Douglas Sirk

A lead director of the German stage in the 1930’s, Douglas Sirk was forced to leave his native land on account of his anti-Nazi politics and a Jewish wife. At the time of his arrival in Hollywood, in 1941, Sirk joined a growing group of Film professionals who came to the US as war refugees.

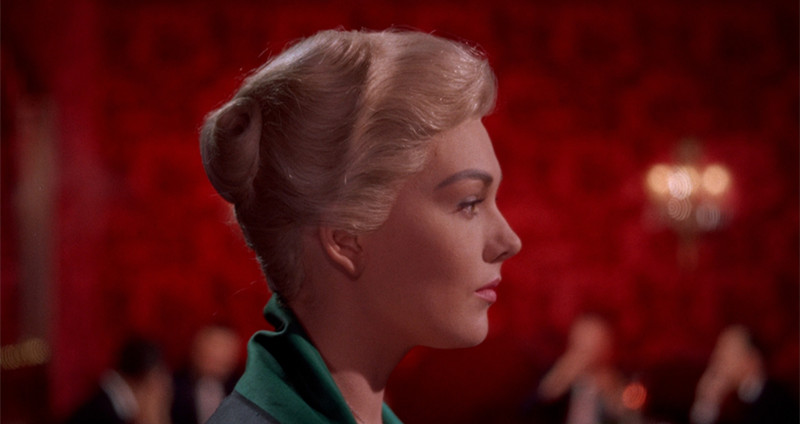

Sirk’s best remembered work was developed at Universal during the 1950’s and often starred screen-legend Rock Hudson. They were usually glossy melodramas about contemporary America’s prejudices and restraints, shot in glorious Technicolor.

Films like All That Heaven Allows, Magnificent Obsession, Written on the Wind and his masterpiece, Imitation of Life, were all huge hits with the public, but failed to impress critics. His reputation as a director grew with time, mostly thanks to the French auteur theory of the 1960’s, which found in his sophisticated style underlying irony and social commentary.

6. Elia Kazan

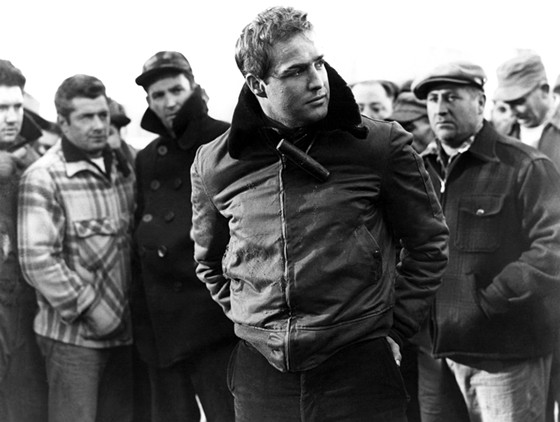

A co-founder of the Actors Studio, Kazan introduced a whole generation of talented performers and essentially revolutionized acting in movies with the usage of ‘the Method’. Among his discoveries were Warren Beatty, Eva Marie Saint, James Dean and Marlon Brando.

His films often carried social concerns, like the 1947 Best Picture winner Gentlemen’s Agreement, which addresses anti-Semitism; and 1949’s Pinky, about racial prejudice. Arguably his best work came in the 1950’s with the release of A Streetcar Named Desire, which he had already adapted on stage; On the Waterfront, a winner of eight Oscars and East of Eden, the first James Dean starring role.

Kazan was also a notorious friendly witness before the House Committee on Un-American Activities in 1952, a decision he never regretted. In 1999, he was awarded with an honorary Oscar among protests and applauses. On the matter, actor Gregory Peck, who worked with him, said “a man’s work should be separate from his life.”

7. Ernst Lubitsch

Lubitsch’s elegant filmmaking style, his witty dialogue and subtle sexual innuendo were such strong trademarks of his films, a term was invented to encapsulate the entirety of the German director’s body of work – The Lubitsch Touch.

In 1922, Lubitsch was selected by America’s sweetheart Mary Pickford to direct her newest film, thus beginning his distinguished American career. Still in Silent film, the filmmaker gave start to his legendary string of comedies of manners, but it was during the early sound age and the Pre-Code days that Lubitsch produced his most acclaimed movies.

A pioneer of musical comedy, Lubitsch discovered singer-actress Jeanette MacDonald and made her the star of three of his early gems: The Love Parade, One Hour with You and Monte Carlo. However, 1931’s The Smiling Lieutenant is widely considered his best effort in the genre. The film starred Claudette Colbert, Maurice Chevalier and Miriam Hopkins – another of the director’s favorite actresses.

Hopkins would later appear in two of his best remembered works, the daring love-triangle comedy Design for Living and arguably his masterpiece, Trouble in Paradise. In his later career, Lubitsch would also release the treasured classics Ninotchka and To Be or Not to Be, before collapsing to a heart attack in 1947.

8. Frank Capra

Francesco Rosario Capra was born in Sicily in 1897. As a boy, he celebrated his sixth birthday on a ship bound to the USA. Like most immigrant families, The Capras long and unpleasant journey was motivated by their dream of joining the American way of life.

Not only would they succeed, but little Francesco would soon grow up to be the film director who best portrayed American values on the screen. In the words of John Cassavetes: “Maybe there really wasn’t an America, maybe it was only Frank Capra.”

Capra made a name for himself at Columbia Pictures during the Depression. Harry Cohn, the studio boss, gave the filmmaker creative freedom and Capra corresponded by putting out a string of hits that single-handedly took the studio out of the infamous “poverty row”.

During his 40-odd years in Movies, Capra made over 50 films and won 3 Oscars. The timeless classics It Happened One Night, Lost Horizon, You Can’t Take it with You, Mr. Deeds goes to Town and Mr. Smith goes to Washington are among them. But Capra is undoubtedly best remembered nowadays by what has since become the ultimate Christmas film, 1946’s It’s a Wonderful Life.

9. Fritz Lang

Although he was born in Austria, Fritz Lang personified the German director stereotype – monocle included. It was in Germany’s UFA, during the rise of the Expressionism movement, that Lang made some of his most celebrated films, among them the revolutionary sci-fi drama Metropolis.

In 1934, Hitler’s propaganda minister Joseph Goebbels offered Lang a lead position in the Nazi regime, as the head of the film industry. According to the director, he fled Germany on the same evening, leaving behind most of his belongings and Nazi-sympathizer wife and film collaborator, Thea von Harbou.

He moved to Hollywood in 1936 and continued to brilliantly integrate popular film genres with a sophisticated visual style. The Expressionistic traits of movies such as The Big Heat, Man Hunt and Scarlet Street, just to mention a few, greatly contributed to the development of the American Noir movement, while establishing Lang’s fame as one of the greatest émigrés in Hollywood.

While in his active years, many critics thought his American phase fell short of the grandeur of his early work, French filmmakers and writers from the Cahiers du Cinéma would later call his Hollywood work that of an expert.

10. George Cukor

Born to Hungarian immigrant parents in Manhattan, Cukor began working as a director at Broadway. His literary adaptations caught the attention of critics and, in 1929; Hollywood selected him to be part of a new generation of directors, who would have the task of working with the newfound Sound technology.

Cukor moved up in the Film world at RKO, under the reign of producer David O. Selznick. There he made What Price Hollywood? And three of his ten movies with actress Katharine Hepburn: A Bill of Divorcement – which earner her, her first Academy Award; Little Women and Sylvia Scarlett.

After his move to MGM, he made the comedy classic Dinner at Eight and successfully adapted Camille to the screen, before embarking in the all-women cast production The Women. At Metro, he also shot some of Hepburn’s greatest vehicles such as The Philadelphia Story and Adam’s Rib.

By the mid 1930’s, Cukor was already considered a master of the so called “woman’s pictures” subgenre. During his 50 years in Hollywood, he directed over 10 actresses to Oscar nominated performances, including Judy Garland for A Star is Born.