Latin culture is rich, beautiful and full of many traditions that comes from years of European colonization and an even richer native culture, making it a very difficult culture to understand but also very interesting to analyze and explore.

The Latin art is the perfect presentation of the many contrasts of its culture. In painting, in literature and in cinema, Latin America has a style that travels in the waters of surrealism, carrying an inner magic, a product of the many cultures that composed America.

Being mostly a continent with many social differences, most Latin countries have several monetary problems that make it difficult for artists to perform. For many years, Argentina, Brazil and Mexico were the main references for the cinematic art in Latin America, due to their power above of the rest of the continents.

But thanks to advances in technology and its opening to people all over the world, this cinema can belong to more than just these three countries. The democratization of the art gave every Latin nation the opportunity to create beautiful pieces of work that can mesmerize any audience.

This list corresponds to the time in which this democratization of the technology bloomed and allowed the artists in every part of the world to develop masterpieces with the minimum of resources. Here in Latin America, that domain is no longer for a few but for all.

1. Post Tenebras Lux (2012, Carlos Reygadas, Mexico)

One of the most exciting names in the cinematic world, alongside Apichatpong Weerasethakul and Shane Carruth, is Mexican director Carlos Reygadas. His style is like a magical communion between God and the film, and the presence of this God (or his absence) influence the mind and the soul of the audience.

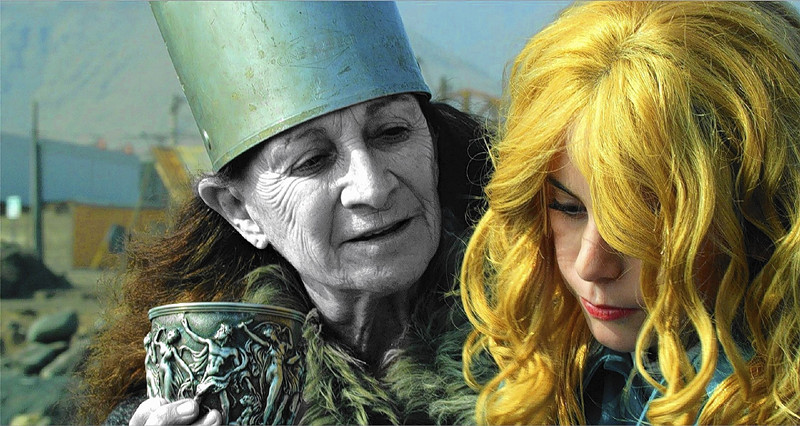

Reygadas and director of photography Alexis Zabé have created some of the most visually stunning films of this century. “Post Tenebras Lux” is the latest but the most extraordinary work this duo has given us to date. With fantastic shots that are more like a dream or nightmare sequence, this film goes further than whatever has been seen, creating the most original movie of this century in Latin America.

With a slow rhythm and beautiful long shots, Reygadas tells the story of a family living in a rural farm world, where they try to adjust to its challenges. But it’s not the story (and its many subtexts) that is important in this film. In all of Reygadas’s films, it is the form and not the content that really conducts us into the substance of what this film is about, and that can be summarized in three feelings: alienation, emptiness, and a relinquishment of God that goes all over the film and gets inside of the soul of the audience.

2. Ixcanul (2015, Jayro Bustamante, Guatemala)

Guatemala has never been at the top of the list in world filmmaking. Most of the films coming from this country are made with poor budgets and are never really done with particularly good craftmanship. But what Jayro Bustamante has done with this movie exceeds any expectations, creating a masterpiece.

“Ixcanul”, which means “volcano” in the Kaqchikel Mayan language, tells the story of a young girl named Maria who dreams about leaving her village, inconveniently based on the slopes of the Pacaya volcano. She sees the chance to make her dream come true if she goes with Pepe, who is about to leave, and he promises to take her with him in exchange for some favors.

The volcano is the symbol of Maria. One represents the other and the dazzling images, filmed by Luis Armando Arteaga, creates the mood in which the ritual of this films begins. A ritual of faith, of self-knowledge, one that is magical and plagued with the desire to break what is socially imposed.

Bustamante tells the story of the burning youth in a teenage girl who wants to rebel against her parents, her society and her destiny, and she has to face the nature in every sense if she wants to forge her own path.

3. Jauja (2014, Lisandro Alonso, Argentina)

Narrating the story of a father in search of his daughter, Lisandro Alonso manufactures a story that breaks time in the present, the past and the future, creating a magical odyssey through the desolate mountain landscapes of deep Argentina.

Dinesen and his daughter, Ingeborg, are traveling into Argentina for a matter of business, because they want to establish in there after leaving Denmark.

The girl finally meets an Argentinian boy and she falls for him. In a rush, both decide to escape, leading Dinesen into a desperate search in which he’s going to find that the love he has for his lost daughter is so strong that can make the time converge in singular places.

The photography, filmed by Finnish photographer Timo Salminen, is more like old illustrations of fairy tales that our mother used to tell us before going to bed. Alonso takes all the similarities from those childhood moments and puts them together, giving us a fantastic, beautiful and intimate film.

4. El Violín (2005, Francisco Vargas, Mexico)

If something distinguishes Latin America it’s the deep contrast between the social classes, the cultural oppression that excludes the natives and the poor, an oppression that led them into a constant state of conflict with the ruling class in an endless war.

Francisco Vargas, a director of documentaries, shows us this side of Mexico that the government and the news barely talks about, more likely trying to hide an obvious situation that asphyxiates the whole continent.

Shot in a beautiful black and white used to mark even more the contrast in the country, “El Violin” tells the story of a community hit by the war, where a family of men has to fight in this rebellion against the established government, which is a resemblance of the Zapatista movement in southeast Mexico.

This unequal war has the rebels hiding and, as they are required to leave their ammunition behind, obligate Don Plutarco to pass infiltrated using his violin to gain the confidence of the army commander. This film, photographed by the duo of Martín Boege and Oscar Hijuelos, is a guide of this part of Latin society that is not used to having a voice.

5. El Club (2015, Pablo Larraín, Chile)

Pablo Larraín has become the most popular and gifted director in South America this century. His films, from “Fuga” (2004) to “No” (2012), have put Chile on the cinematographic world map again, positioning himself as the centerpiece of the new Chilean cinema.

“El Club”, a powerful and awkward film, tells the story of a group of Chilean priests, excommunicated for terrible crimes including children rape and kidnapping. They are brought to a house in this little town where nothing happens, making it the perfect place to hide them instead of taking them to justice, as the church used to do in these cases.

What Larraín does at this point is drive us into a very claustrophobic place, surrounded by five of the most perverse criminals in South America, turning this house a pressure cooker where the priests all have to face their own sins.

Filmed in the most sordid way possible, photographer Sergio Armstrong and Larraín himself send us into an unstoppable journey of decay and qualm, questioning the religion, the legitimacy of the representatives of the church, and the darkness of the human soul.

6. Stellet Licht aka Silent Light (2007, Carlos Reygadas, Mexico)

From the very beginning of this film, you can see the masterfully crafted detail in the direction of this beautiful story that puts God right in the middle of the picture.

Director of photography Alexis Zabé worked in a very simple but beautiful way, with long shots, delicate close ups and places full of natural light, a light that seems to come from God Itself, helping to reach a closer point in this film.

Facing love for two women, Johan deals daily with his inner problems and also with his duty as a family man. Right in the middle of a strongly religious Mennonite community, Johan is doomed by his acts, which define him as a bad man, despite the love he professes to his family and his congregation.

Reygadas puts the cards on the table, showing us that the essence of God and love are bound together, and that the goodness of a man cannot be measured with his sins of the flesh but with his true feelings about whomever surrounds him, leading to a renaissance of the spirit and the sacred.