The entire history of humanity has revolved around hierarchical structures. Some were organised and austere, such as feudalism in medieval Europe, which involved a clear distinction between nobility and peasantry. Others, however, were lax and anarchic, such as the system of communes and slaves in ancient Rome, which required cooperation from all parties; in the feudal system, peasants (also known as serfs) had no choice in their menial duties and lives.

In another section of the world, Japanese shōens were estates during the 8th to 15th centuries, that housed wealthy clans and aristocratic families; shōens were tax free, and their owners managed to gain power relatively quickly, which threatened to destabilise the emperor, throwing the hierarchy into a maelstrom of chaos for many. Even today, in government, all people are connected to a form of hierarchy.

Excluding governments and political power, hierarchies have also emerged in other aspects of life, such as the latent social hierarchies that have been manifested in social politics (racism, feminism, LGBTIQ rights, for example) and social situations (represented in Foucault’s on power that largely discuss social status developed through body language and movement).

Despite the differences of the following films – some entangled in politics, and others in social sects and subgroups – these all have one intrinsic idea driving them: the unmitigated study of the human condition.

More specifically, this is about the human condition (or, metaphysics) in terms of hierarchy, and the preoccupying twin leitmotifs of modern society: dominance and superiority. This article will explore how carefully-formed hierarchies react when certain people are faced with adversity, prejudice, social pressures and opportunity.

1. Battleship Potemkin (1925)

The quintessential Sergei Eisenstein film, the epitome of the propaganda film, and one of the most apt examples of political relevance in all of cinema, released with impeccable timing: Battleship Potemkin.

This is a film that swayed the entire world to sympathise with the plight of the Marxist groups in Russia, which Joseph Goebbels named “a marvelous film without equal in the cinema”. The film follows the Revolution of 1905 in Tsarist Russia, which aimed to transform the political climate of Russia, allowing for more equality and input from the people.

The people in the film are trying to break the hierarchy, giving the rigid system some pliancy. This film is about dissatisfied people rebelling against this system, trying to crawl out of being trapped at the bottom of the social hierarchy by an oppressive government. Even though it was a representation of an event that occurred 20 years prior, there was rejuvenated support and hope for the Bolshevik political party following the death of their leader in 1924, Vladimir Lenin.

2. Freaks (1932)

Director Tod Browning, a former contortionist for a travelling circus, was eager to present this sympathetic tale of circus freaks fighting against surrounding inveterate prejudice.

Based on Tod Robbins’s short story, Spurs, the film follows the romantic plight of a dwarf named Hans (Harry Earles), a sideshow freak who falls in love with a beautiful and cunning trapeze artist, Cleopatra (Olga Baclanova). Cleopatra, upon learning of Hans’s riches through inheritance, plots her marriage to him, and his subsequent murder. The first part of the plan is executed with success, but the circus freaks begin to catch on.

Originally 90 minutes, cut down to a mere hour for being deemed obscene, the film is entrenched in the concept of social hierarchy, highlighting it as a flawed model. The “freaks” are kind and accepting, albeit persecuted and reviled by society. On the other end of the social gamut sits the people without defects or other aberrations, namely, the strongman and Cleopatra. This film is a study of how those promulgated as “freaks” are in fact the most moral and ethical, and therefore the most likeable.

Critics hated this film upon release, Variety publishing a review complaining that “it is impossible for the normal man or woman to sympathize with the aspiring midget”. Time has passed, and the film has become a cultural and critical classic since.

3. The Rules of the Game (1939)

Perhaps the most praised film by the most praised director ever, Jean Renoir’s The Rules of the Game “taught [Robert Altman] the rules of the game” in filmmaking, and was Bernardo Bertolucci’s favourite film. Even Orson Welles’s masterpiece, Citizen Kane, reportedly drew many influences from Renoir’s classic. His art transformed the meaning of being a filmmaker, introducing a mastery of observational filmmaking, long takes, deep focus, and the camera gaining a personality of its own.

These had all been experimented with in the past by the likes of Hitchcock, Lubitsch, Murnau, Dreyer and Lang, though never with the confidence and fusion that Renoir was able to deliver in this film.

As well as this, The Rules of the Game captured the aura, the people and the politics of France in 1939, on the brink of war. Considered a “portrait of class manners” (Owen Gleiberman), this acerbic social commentary, rather than distinguishing between the upper class and the servants in the film, brings to the fore their similarities.

The film is replete with characters striving to ignore their problems, maintaining a collected exterior in the face of personal tragedies, and awful revelations. Even the most poignant of moments resolve themselves in anticlimaxes.

These are the “rules of the game”. Those who do not play by the rules reach the finale of the film without respect or happiness. The social rules and conventions dictate the actions and reactions of characters, who must play to the hierarchy. They all have their own rules in the game.

4. On the Waterfront (1954)

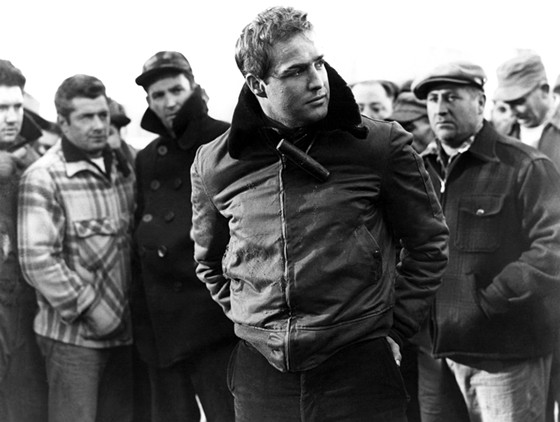

Terry Malloy (Marlon Brando), a former boxer, works on the docks while his mob-connected brother cajoles him into assisting in murders, remaining oblivious to the fact.

As Malloy comes to understand and develop a sense of remorse, he responds to orders and requests with chagrin. His reluctance to obey the corrupt union boss, Johnny Friendly (Lee J. Cobb) – also Terry’s brother’s boss – lands Malloy in disrepute with the criminals. After agreeing to testify against Friendly, Malloy becomes unemployed and ostracised from society.

Elia Kazan’s film was extremely personal to the director, who was cast to the bottom of the social hierarchy by his friends and colleagues after being a witness in a few House of Un-American Activity Committee hearings, which were influenced by McCarthyism.

These were paranoid witch-hunts for former communists, prompted by the ever-simmering Cold War. Many people working in the film industry were targeted, which resulted in the infamous “Hollywood blacklist”, which effectively destroyed the careers of many. Kazan’s cooperation in the naming of communist actors, directors and writers was never forgiven by some.

Despite controversy, the film won eight Academy Awards, and is now considered a classic, particularly for being revolutionary in acting, Brando popularising method acting.

5. The Apartment (1960)

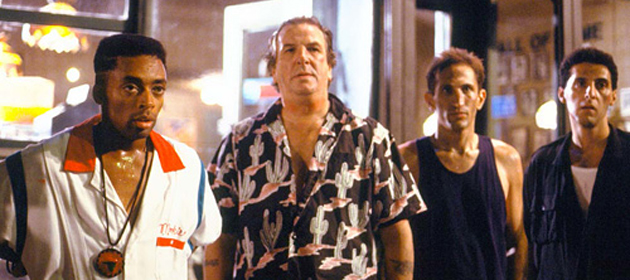

Jack Lemmon stars in The Apartment as C.C. Baxter, a low-level employee in an insurance corporation, affectionately referred to as “Bud” and “Buddy Boy” by his senior associates. Why are they so affectionate? Because “Buddy Boy” allows them access to his apartment so that they can have affairs without the risk of their wives barging through the door.

Of course, Bud has his own motives: to climb the corporate ladder and succeed in business without really trying. Unfortunately, this whole experience becomes a taxing nightmare for Lemmon’s guileless character. Bud becomes unknowingly embroiled in a triangular love affair with his boss and the elevator operator; he becomes plagued by apprehension, even despite a raise and his own office.

Billy Wilder’s film, a critical and commercial success, considers the exploitation of the corporate proletariat by more distinguished and powerful members. The two main characters, Bud and Fran (the elevator operator, played by Shirley Maclaine), are repeatedly used by the higher-ranking individuals, both attempting to tear down the feudalistic system of the business world.

6. The Conformist (1970)

Often considered one of the greatest Italian films to grace screens all over the world, Bernardo Bertolucci’s “expressionist masterpiece” (Kevin Thomas, Los Angeles Times) is a work of beauty.

The variegated set pieces that surround a lively atmosphere are painfully discordant with the portrayal of fascism and liberal anguish. Vincent Canby, of The New York Times, called the film’s visual style, “rich, poetic, and baroque”. The contrast provided by Bertolucci makes for an uneasy two hours, to say the least.

The film follows a man, Marcello Clerici (Jean-Louis Trintignant) ordered to murder his former university professor, Professor Quadri (Enzo Tarascio). Clerici respected Quadri, and the two mingle and discuss politics. Quadri’s crime is being an anti-fascist intellectual, and Clerici is his pusillanimous and prospective assassin.

Clerici tries throughout the film to maintain respect and a position of social authority by conforming, even becoming anti-fascist and abandoning his close companion when Mussolini falls. He is trying to survive the political turmoil, and is treated as a spineless coward for his lack of conviction.

7. One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest (1975)

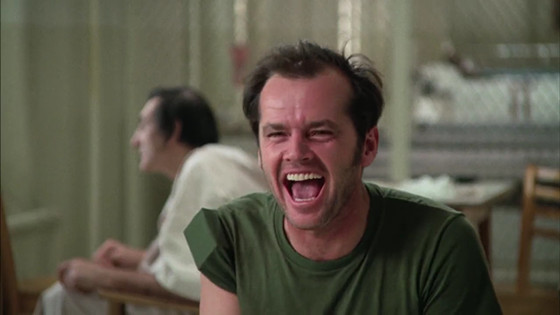

Set in a mental institution, Miloš Forman’s adaptation of Ken Kesey’s countercultural novel is a frenzied, fast-paced and indelible filmic endeavour, arriving at a sombre conclusion. Forman’s outing as a director in the United States, following a reasonable amount of critical success for his work in the Czechoslovak New Wave movement (including the satirical, The Fireman’s Ball), One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest is considered his masterwork.

Jack Nicholson stars as the charismatic and rousing Randle P. McMurphy, wrongly committed to the institution. McMurphy, weary of the treatment of the patients by the staff, particularly Nurse Ratched (Louise Fletcher), delivers several peremptory monologues and demands. His brusque demeanour isn’t quelled when he comes to realise the nature of his perfunctory ensemble of terrorised and manipulated peers.

His outbursts build to a crescendo, his mounting frustration parallel to his understanding of the hopelessness of the situation. This is not a fair system, and the nurses are always superior. This is a bleak requiem for the death of bravado, life stifled by the stringent hierarchy.

Cleaning out the top five Academy Awards, winning Best Picture, Best Director, Best Actor, Best Actress and Best Adapted Screenplay, most critics awarded the film colossal critical acclaim. Roger Ebert placed the film in his “Great Movies” list, giving it a full four star rating.

8. Fitzcarraldo (1982)

Director Werner Herzog’s fourth collaboration with volatile actor, Klaus Kinski, Fitzcarraldo is considered by some to be his greatest achievement as a filmmaker. The film tracks the journey of Brian Fitzgerald, nicknamed “Fitzcarraldo”. He is a rubber baron whose foremost ambition is to build an opera house in the jungles of South America.

To attain this dream, Fitzcarraldo is forced to move a steamship over a large portion of land, battling against a steep gradient. In some ways more than expressing his love for opera, Fitzcarraldo is intent on disproving those who denigrate his desires, to reverse their snide remarks and humiliating treatment of the titular character. He is trying to find respect among his peers, to climb the social rungs.

Herzog’s film is enhanced as an experience by the fact that he, with the help of locals and extras in the film, was able to shift the steamship across the section of land. On top of this, Kinski’s outbursts were more turbulent than ever, generating a mercurial relationship between him and the director. Their erratic friendship was explored in Herzog’s 1999 documentary My Best Fiend.