The renaissance of the Australian film in the early 1970s, now labelled the Australian New Wave, gave birth to an industry hell-bent on displaying hallmark qualities of ‘Australianness’. Originally kick-started through a spate of sex-infused ‘ocker’ comedies, Australian cinema would gradually ascend, or descend, into an industry defined by nationalistic landscape films that looked to capitalise on the stereotypical qualities deemed ‘Australian’.

Amidst all this patriotic carnage however, existed moments of cinematic beauty. Names like Peter Weir, George Miller and Mel Gibson crafted films that broke out of the micro-budget shackles of Australian film, impacting and influencing cinema on a global scale. Here are the ten essential films of the Australian New Wave.

1. Wake in Fright (Ted Kotcheff, 1971)

Canadian director Ted Kotcheff filmed Wake in Fright in 1970, predating the birth of what is now known as Australian cinema. This meant that, unlike the vast majority of films released in Australia at the time, Wake in Fright was separated from government funding, a fact which allowed the film to explore the Australian outback in a way that was antithetical to the product of Australianness that Australian cinema would come to represent in the following decade.

The film follows a disgruntled schoolteacher who is trying to return to Sydney for a vacation, a trip that takes him through the town of Bundanyabba, or “The Yabba”, as it is known by the locals.

The teacher, John Grant, becomes trapped in this rural hell when he loses all of his money during a drunken game of two-up. Unable to leave the town, Grant becomes reliant on the aggressive hospitality of the locals, men who define themselves through their masculine output, be that pub brawls, excessive drinking or kangaroo shooting.

Wake in Fright premiered at Cannes, where it was in competition for the prestigious Palme d’Or and opened to critical acclaim. Subsequent successful theatrical releases in France and Great Britain were not matched in the domestic box office. Perhaps the film’s damning condemnation of the ‘Aussie’ way of life was too close to home, or as Australian icon Jack Thompson lamented,

“it was so embarrassingly accurate”. The negative local reception meant Kotcheff’s film had little influence on the oncoming rush of Australian films, and only recently has the film begun to be discussed as one of the greatest Australian films of all time.

2. Sunday Too Far Away (Ken Hannam, 1975)

Following a spate of ‘ocker-comedies’ that essentially kicked off the Australian New Wave, yet lacked critical appreciation, Ken Hamman’s Sunday Too Far Away presented arguably the first commercial and critical success of this new Australian cinema.

The film is essentially a workplace milieu of the Australian outback shearer, using a group of decaying old men to act as a metaphor for the decline of the male labourer in outback Australia.

The film adopts a naturalist style to serves to authenticate the entire picture, a style that borders on documentary film in the brutal shearing sequences, in which Hannam allows his camera to sit back in a passive manner and observe the characters.

This documentary-style naturally has a realist effect, an effect which posits the characters and the setting as a true embodiment of outback Australia. The film shies away from depicting the fabled Australian bush in a grandiose fashion, instead Hannam merely points his camera at the isolated setting, allowing the natural setting to tell the story.

Such is the unflinching and rather negative picture the film paints of the Australian outback, the film seems to act as a reaction to a trend of films that had not yet been unearthed, that of the male-ensemble landscape film that would come to dominate the late 1970s and early 1980s in Australian cinema.

In reality however, the film helped inadvertently kicked off this trend, with Jack Thompson’s loser hero persona lending itself to a glut of Australian landscape films, while Hannam’s laconic and laid back style would remain throughout the majority of Australian cinema throughout the New Wave.

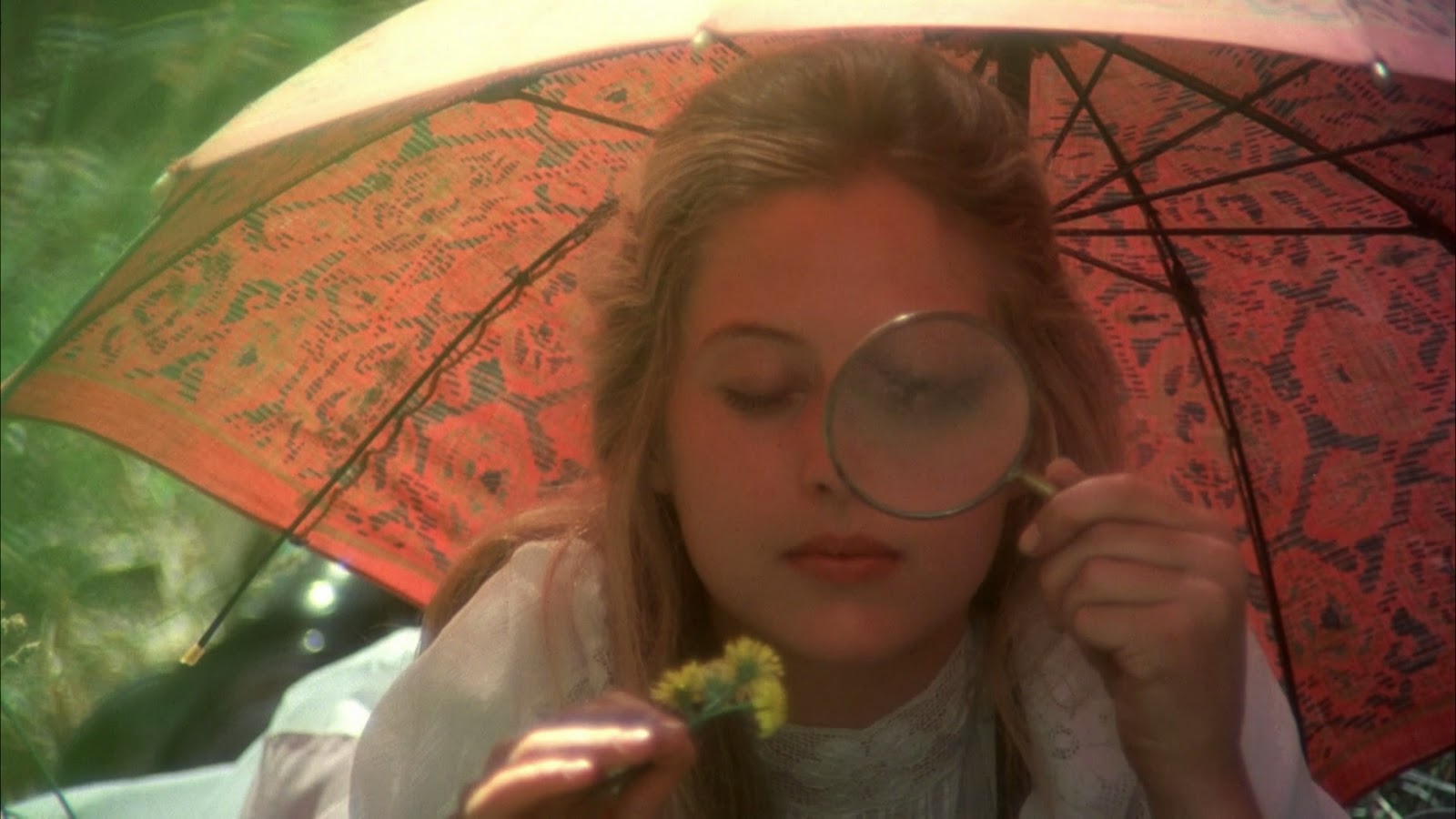

3. Picnic at Hanging Rock (Peter Weir 1975)

Peter Weir’s Picnic at Hanging Rock is somewhat of an oddity when placed in the context of the Australian New Wave. Arriving soon after the birth of an Australian film industry, the film brought qualities not seen before on Australian screens.

Based on Joan Linsday’s 1967 novel of the same name, the adaption takes place on Valentine’s Day in the year 1900, where a group of Private schools take a picnic to the real-life Hanging Rock, a geological formation in central Victoria. When three of the girls and of the college’s mistresses disappear among the labyrinth of the Rock, a frantic search is quickly undertaken.

What is so fascinating about Peter Weir’s film is the lack of narrative progression that he offers, the film, like the search for the missing girls, just seems to peter out. In adapting Joan Lindsay’s novel, Weir essentially directed the first art-house film of the New Wave, quickly removing his film from any notions of Hollywood period piece and instead infusing his film with a European avant-garde aesthetic that refuses to give in to any notions of melodrama or normality.

Where the film forgoes narrative clarity, it makes up for it in mood, atmosphere and an abundance of themes, touching on ideas of sexual awakening and the clash between Western civilisation and the primordial landscape.

On a more technical level, the mixture of period-film themes and art-house cinema is achieved through delicate and dream-like cinematography, a look that was influenced by early Australian Impressionism, while the film’s darker moments are aided by a quite haunting score that seems to linger long after the panpipes drift away.

Picnic at Hanging Rock has had a lasting impact on Australian and global cinema. Following the film’s success, a plethora of literary adaptations appeared on Australian screens, while on the international spectrum, films like Sofia Coppola’s The Virgin Suicides display close ties to Picnic’s formal and thematic elements.

Finally, watch out for two performances from two future Australian stars. Wolf Creek’s maniacal killer John Jarratt appears here without butchering any backpackers, while Oscar-nominated Jacki Weaver is almost unrecognisable in a small role.

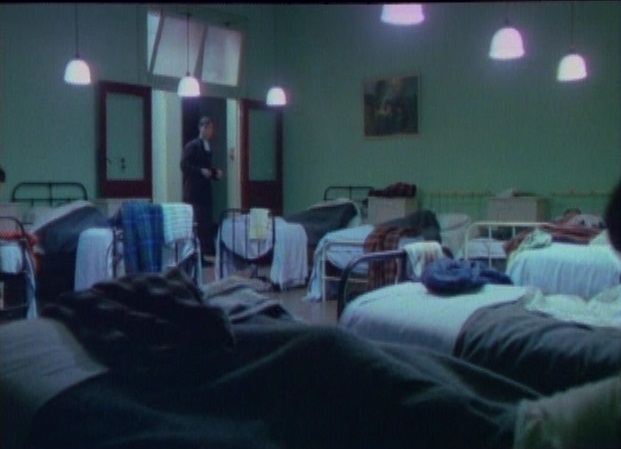

4. The Devil’s Playground (Fred Schepisi, 1976)

Fred Schepisi’s initial foray into the Australian New Wave arrived in the form of The Devil’s Playground, semi-autobiographical film detailing his own training for the priesthood in the 1950s.

After the critical successes of Sunday Too Far Away and Picnic at Hanging Rock, mainstream Australian cinema of the 1970s and 1980s could be generalised into two categories: landscape films and social realist films. The Devil’s Playground is an example of the latter, an urban, densely detailed film that acts as a precedent for Australian cinema that lasts to this day.

The narrative follows a 13 year old boy in training for the priesthood who is racked by the guilt he suffers for having sinful, sexual thoughts. Accompanied in this theme of Catholic sexual repression is Brother Francine, who stalks the halls of the college in search of children not upholding the Church’s strict rules.

13 year old Simon Burke’s portrayal of a conflicted but devout Catholic student won him an Australian Film Institute (AFI) Award for Best Actor, marking him as the youngest to do so, while the film also won Best Picture, Best Director, Best Screenplay and Best Achievement in Cinematography at the 1976 ceremony.

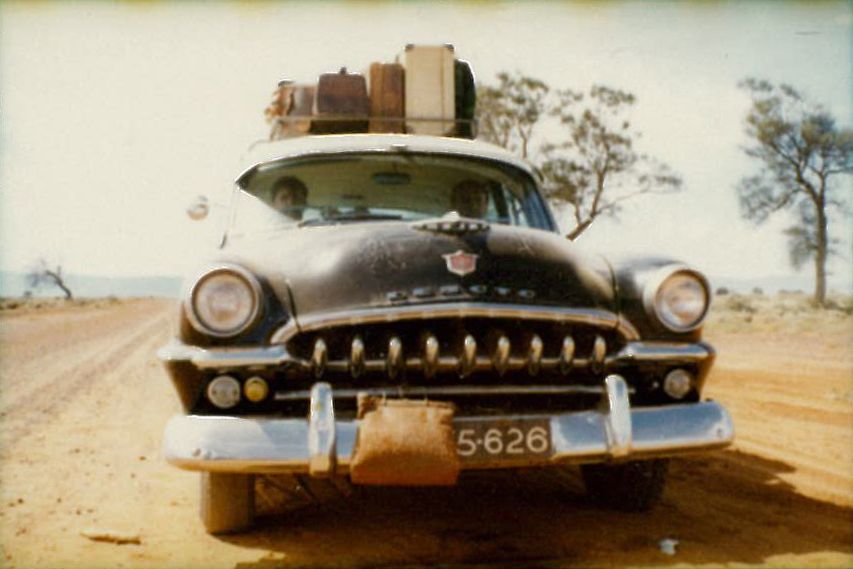

5. Mad Max (George Miller, 1979)

As previously discussed, Australian mainstream cinema tended to be divided between landscape and social realist affairs, films that were draped in a realist tradition that had existed in Australian cinema since the end of the Second World War. So when George Miller’s 1979 dystopian masterpiece came to Australian screens, it was a welcome change.

The dystopian world that Miller created hadn’t been seen before in Australian cinema, an ambition that outshined the dominant mode of Australian film at the time and promoted an outright fear of the outback.

In the not too distant future, society is on the verge of collapse and it seems that who controls the roads controls the world. Keeping this in check is a special police force, home to one Max Rockatansky, a disillusioned but talented driver.

While the film will be forever remembered for its stunningly brutal and realistic car stunts, the first film in the recently revived franchise remains steeped in a down-beat style. While the film is a rare example of a genre film in the New Wave, it is still recognisably Australian. The loner-hero figure of Mad Max, the relaxed and simple dialogue and the rural Victorian setting are all factors which serve to distance the film from Hollywood action and science fiction cinema.

It is easy to forget that the true ‘Mad’ Max is only really created in the film’s final act, where the movie turns into an ever darkening revenge flick, but this creates a fascinating experience upon re-watching, as we get to witness the birth of the only true action icon of the Australian screen.