Steven Spielberg is one of the most influential directors of the late 20th century. While some serious film lovers have brushed him off as trite or too sentimental, others put him on a pedestal as the author of their childhood.

Whether you grew up in the 80’s or 90’s, Spielberg’s films most likely had a big influence on your childhood. He’s influenced filmmakers like J.J. Abrams, Edgar Write, and even David Fincher. But Spielberg was once a kid too who loved movies and revered filmmakers.

This list is composed of ten films that influenced how Spielberg makes movies, hopefully it can give insight into where some of his most infamous themes and techniques came from.

1. Lawrence of Arabia

David Lean’s 1962 epic masterpiece is certainly one of the most influential American films of all time. In fact, if you need a definition of epic filmmaking, one need only to look at this seminal war drama.

From its gorgeous 70mm Super Panavision, to the solid screenplay, breathtaking locations, and Peter O’Toole’s mesmerizing performance as the “most shameless exhibitionist since Barnum and Bailey”, it’s difficult to not be swept up in the grandness of it all. Since its release, it’s made critics, audiences, and wannabe filmmakers gush as well as cry blasphemy if anyone was ever caught watching a panned and scanned version.

So no one can blame a teenaged Steven Spielberg when he was so blown away by the picture; he needed a few weeks just to take it all in. Spielberg first saw Lawrence in high school, it set him on a journey to know more about the techniques of cinema.

Being raised in the desert of Phoenix, Arizona, Steven related with Lawrence’s love of the desert. It taught him the importance of setting; that an environment can be almost like a character in the film. No doubt he was thinking of how Lean shot the desert when he was shooting in similar locations for Raiders of the Lost Ark.

Spielberg even got to meet his directing hero when helping with the film’s restoration and listened as Lean gave him a personal commentary while they watched the film together. His wonder and awe at Lean’s masterpiece lit the spark that would drive him to make movies that moved audiences the way he was moved by Lawrence.

2. Rope

It wasn’t enough for Alfred Hitchcock to enter the world of movies in color, he had to add some smoke and mirrors to convince the audience the movie they’re watching was shot in one take. In the film, two friends murder a fellow student colleague, hide his body in a wooden chest, and then play host to the victim’s friends and relatives in the same room where his body is stored.

Since this murder was done for curiosity and boldness’s sake, one of the killers is on edge that they’ll be found out, while the other seems to ride the thrill of the experience. Though the movie obviously cuts up to 10 times, sometimes disguising them, sometimes not, it nevertheless taught Spielberg two essentials in filmmaking: how to stage a long take and how to make your audience sweat.

Spielberg likes to move the camera, creating multiple setups with just one shot. It’s a trick that’s become a dying art form. In an age where most comedies are single head-on shots of people ad-libbing and action movies are trying to see how many cuts they can make per-second, Steven’s one of the few mainstream Hollywood directors still using this classical Hollywood style of set-ups.

Hitchcock, in Rope, employs his most notorious technique of giving the audience privy information, then letting them bite their nails as the characters on screen unknowingly brush too close to the horrors that lie just out of sight. Similarly, the shark in Jaws is kept out of sight, with only a camera POV to insinuate its presence. If there’s anything Spielberg took from Hitchcock, it was how to create suspense.

3. The Wizard of Oz

The audience is introduced to the mundane world of Kansas, so boring it’s in black and white. Then, we are transported to a magical world where the adventure can now begin. Movies themselves, do the very same thing, transporting us to other worlds and setting us on adventures we seldom experience. Like going to Jurassic Park or the temple of doom, Spielberg also loves to take the audience from the real world to some place fantastical.

Victor Fleming’s staple of early Technicolor is the epitome of dreams come alive on film. The movie is a literal dream. While others may have been inspired to follow their dreams or make musicals for MGM studios, Spielberg more so admired Victor Fleming’s ability to virtually be invisible in style and genre with his direction.

It’s true, telling great stories means more to Spielberg than adhering to any specific kind of story. This frees him up to make thrilling adventure films like Jurassic Park, to gripping war dramas like Schindler’s List. What he took from Victor Fleming was his seemless ability to go from The Wizard of Oz to Gone With the Wind to Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde.

4. Bonnie and Clyde

When Bonnie and Clyde came out in 1967, it ushered the way of the New Hollywood movement; breaking boundaries with its overt sexuality and, what was then, shocking violence. While this film is based on the real life bank robbers, Clyde Barrow and Bonnie Parker, and Spielberg’s second feature, Sugarland Express, is a biographical film about two completely different outlaws, the similarities are evident.

Spielberg’s Sugarland Express both balances humor and drama in a way that’s reminiscent of Arthur Penn’s film. While Sugarland isn’t one of Steven’s best films, it’s certainly one of his most nuanced. Very few times are you aware of Spielberg’s more over-indulgent sentimental themes. Much like Clyde and Bonnie, the two leads in Sugarland evoke the audiences’ sympathy while they admittedly make tragic decisions along the way.

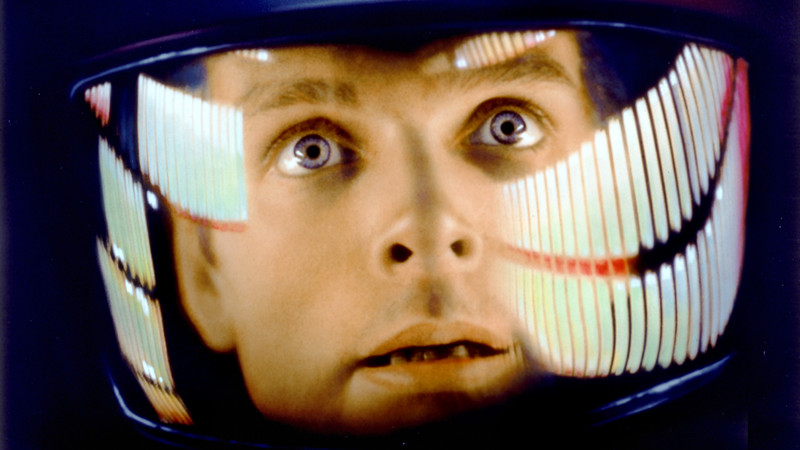

5. 2001: a Space Odyssey

Spielberg first met Kubrick in 1980, and though the two directors couldn’t be more different in style, the two struck up an unlikely friendship. Spielberg, recognizing the immense talent in Kubrick, revered his films, even if he didn’t necessarily like them at first. While Kubrick saw in Spielberg someone who could make films that embodied the joys of childhood.

Spielberg first saw 2001 while he was a student at Cal State, already a fan of Dr. Strangelove. For the first time, Speilberg felt the impact of a film’s ability to transport you to a mental state of euphoria and though Steven admits he’s never taken drugs, 2001 took him higher than he’d ever been in his life.

Despite what you think of 2001: A Space Odyssey, one cannot deny the sheer artistry involved to bring the world of space and beyond to life in such a realistic fashion. It’s easy to suspect that after seeing this film, Spielberg realized some of his more imaginative dreams as a director were now possible.