Its chiefest export being patriotism, and its greatest commodity being self-assurance, America is known as a proud nation. Indeed, this pride is not without merit in the fields of filmmaking. This economic powerhouse, cultural incubator, and altogether well established nation has been heavily involved in the art of cinema since its inception.

Inventor Thomas Edison was at the helm of inventing the kinetoscope, which allowed one person at a time to view a moving picture. This in turn inspired the cinematograph, invented by the French Lumière brothers, for larger audiences.

After this, the American film industry was to feature stars like the Marx brothers, and innovative directors like D.W. Griffith, who would soon make the controversial The Birth of a Nation in 1915, now infamous for its blatant racism and outdated views. Even considering the controversy, The Birth of a Nation is a landmark film that, for the first time, established a high level of quality in cinema, and created benchmarks in the craft.

Twelve years passed, and the film The Jazz Singer arrived into cinemas, starring Al Jolson, known for his signature blackface. This was the first ever film with dialogue, a ‘talking picture’. Again, this evolution of the motion picture was produced in America.

America has a proud tradition that resounds through the chambers of cinema. It comes as no surprise, therefore, that so many films from the great big US of A begin their titles with the word, ‘American’. Some are proud proclamations of their heritage, history, culture and country. Others, however, are seething admonitions of widespread debauchery and glorified opulence, as well as a ‘style over essence’ adage.

These are all films that personify America, in manifold ways from manifold perspectives. These are the films that tell exactly what it means to be American.

1. Citizen Kane (1941) (Originally Titled “American”)

Originally titled by Welles as American, RKO head George Schaefer suggested the title Citizen Kane. The film is considered by some to be one of the first ever that criticises the ‘American dream’. The film is about Charles Foster Kane’s life, the film opening with the iconic and enigmatic line, “Rosebud.” In this line lives regret.

Easily listed in Roger Ebert’s Great Movies list, with a full four out of four stars, the 1941 film didn’t even make a million at the box office, failing to recoup its budget. Though it won critical praise at the time of release, the film took years to receive the widespread acclaim and popularity that it has today. Often touted as the greatest cinematic endeavour of all time, Orson Welles’s film was a narrative and technical triumph in the filmmaking arena.

A newsreel reporter announces Kane’s death at the beginning of the film, leading viewers through a mosaic of Kane’s life, and the audience comes to realise that for the last few decades, if Kane wasn’t reporting the news, he was the news.

The film then arrives at the beginning of Kane’s career. “I’m an American,” he declares, just finding his first taste of triumph, “always been an American.” Kane is a bona fide celebrity, a media tycoon and one of the richest men in the world, a future which is predicted by Kane’s father in an early flashback to his childhood.

The world is at his feet throughout the film, and his death is mourned by the masses, receiving massive publicity. However, this celebrity status doesn’t preserve Kane’s upbeat, charismatic persona. Kane begins a gradual transformation and decline, becoming domineering and temperamental; he is a total recluse by the final chapter of his life, bitter and alone.

Citizen Kane is about living the ‘American dream’, and dying alone as a result. The original title, American, told of the desire to achieve the dream of millions of Americans, whilst sarcastically decrying the ideal. Known as an essential American film, it is ironic to consider that Citizen Kane is a complete denunciation of the ‘American dream’.

2. American Graffiti (1973)

Otherwise known as the soundtrack to life in the 50s and early 60s, George Lucas’s second film was a seminal hit among audiences all over the western world. Boasting a cast with Richard Dreyfuss, Ron Howard and Harrison Ford, who would all go on to prestige and wide acclaim, American Graffiti would soon become a true classic.

The film has spawned innumerable attempts to emulate something so nostalgic, hilarious and relatable, whilst retaining such a high level of quality. This is a testament to American Graffiti’s timelessness and unremitting popularity.

The film follows several different characters fresh out of high school and about to enter college life. They drink, they flirt, they cruise, and they destroy a couple of cars while they’re at it. The film is revolutionary for taking place over the course of one night, much like Bicycle Thieves (1948) and Cleo From 5 to 7 (1962). This narrative technique had been used many times in the past, in arthouse and experimental cinema.

American Graffiti was Lucas’s attempt at making a mainstream film after his niche sci-fi film THX 1138, and with an Italian neorealist approach, he merged mainstream and arthouse styles in the teen classic. It is often theorised that Lucas was inspired by Peter Bogdanvich’s similar The Last Picture Show, released just two years earlier.

It becomes obvious that this film is a nostalgic tribute to a generational staple in American culture, Lucas’s understated romance with what it meant to be young and American in 1962.

Most centrally, this is captured by the rock and roll soundtrack with Chuck Berry, Buddy Holly, and The Platters; Lucas himself explained that he felt “rock radio” to be “an American form of graffiti”. Often imitated and seldom matched, American Graffiti is a landmark film ahead of its time.

3. American Gigolo (1980)

Written and directed by Paul Schrader, best remembered for writing the Taxi Driver screenplay, American Gigolo was a lukewarm success, receiving mixed reviews. The film follows Richard Gere as a male prostitute, Julian, a pretentious and decadent narcissist. At the same time, Julian finds pleasure and meaning in satisfying older women: he enjoys making these women happy, which makes the character sympathetic.

When he is accused of murder, Julian’s life falls into despair. The character is ambiguous and somewhat distant from start to finish. Due to this, some critics, such as the staff of Variety, felt that the film was “[evasive] to its core”. Geoff Andrew of Time Out saw the film as feeling “academic”, which “[failed] to stir the emotions.”

The film received some positive reception, such as Roger Ebert’s three and a half star out of four review. He saw the film as “a study in loneliness” rather than an accidental despondence that others had observed. Gere’s muted acting style aided in developing the character’s complacent attitude, which – as with the film – received mixed reviews.

The film succeeded in creating a grandiose, yet aloof, atmosphere, retaining a tone of loneliness despite Julian’s collection of cars, clothes and obvious wealth. This has been considered a comment on the lifestyle of many Americans, which is focused on materialism, and neglects emotional fulfillment.

Julian is a victim of this lavish lifestyle, and even with a steadily growing relationship with a client, the wife of a senator, he retains his ambivalence to life and inherent loneliness. This facet of life as an American is unpleasant and underwhelming in American Gigolo.

4. American History X (1998)

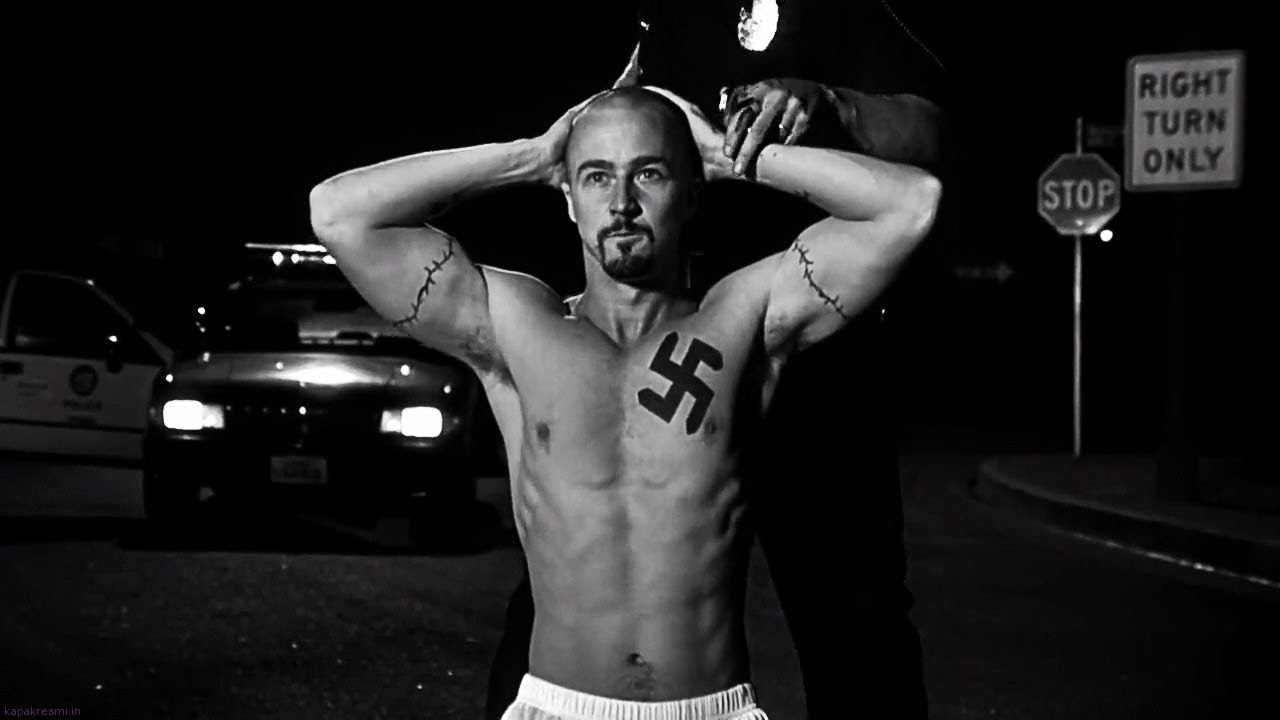

Edward Norton gained 30 pounds of pure muscle to play neo-Nazi skinhead Derek Vinyard. Famous for editing disputes and the director, Tony Kaye, disowning the final cut of the film, and infamous for a certain curb-stomping scene, American History X is a film mired in controversy. Due to this and its polarisation of critics, the film earned one solitary Academy Award nomination, for Norton’s performance.

Following Derek Vinyard’s incarceration and subsequent disillusionment with the neo-Nazi ideology, the film is a cautionary tale of ignorance and bigotry, and, eventually, reform. Before prison, Derek is idolised by his younger brother and protégé, Danny.

Upon his release into society, Derek is anxious to unteach his brother his once ignorant and askew beliefs. Some criticised the film for succumbing to emotional manipulation and advocating shallow ethics, though many were positive about the film, Roger Ebert awarding the film three out of four stars.

The title, American History X, is taken from Danny Vinyard’s alternative American history class when he is removed from his regular class for penning an on Mein Kampf, Hitler’s autobiographical book. The title is essentially dealing with the oft overlooked elements buried in the recesses of American history, most primarily racism. This is a caustic remark on the typical notion of ‘American history’, and its accompanying naive patriotism.

5. American Beauty (1999)

“Look closer…” tempts the tag line of this film, enticing the audience to take a real look at a seeming suburban utopia. Of course, director Sam Mendes does look closer, finding the figurative severed ear in the garden. Much like David Lynch’s Blue Velvet, American Beauty finds white picket fences, roses (aptly named American Beauty roses) and neatly trimmed grass all before a row of drearily repetitive houses.

This is what it means to be beautiful: to have a nice garden out front of a nice house in a nice neighbourhood with a nice family. This last step is optional, as the Burnham’s fumble out the door near the opening, Annette Bening’s Carolyn too hurried and solipsistic to see Kevin Spacey’s Oscar winning turn as Lester spilling his briefcase all over the pavement as anything other than a hindrance to her, and Jane (Thora Birch) – their daughter – looking away, shrinking into a cocoon of genetic humiliation.

What follows is a 100 minute journey through Lester’s apathy-ridden midlife crisis, as he feels “sedated”. At times pathetic, often droll and sparingly poignant, Lester’s ambivalence to life is only broken in small moments of minor successes that engender eager cheering from viewers of his bleak life as it turns around.

Picking up five Academy Awards out of eight nominations, American Beauty was the most successful film released in 1999, the same year as Fight Club, The Sixth Sense, The Green Mile, Magnolia, Boys Don’t Cry and The Matrix among others. Having managed to find such achievements in a year so littered with commercial and critical successes is incredible in and of itself. Additional to these accolades, it was named “a remarkable debut from Sam Mendes” by Peter Bradshaw of The Guardian, and topped Peter Travers’s favourite films of 1999.

While the film is replete with picturesque locations and alluring shot composition, the physical beauty is but a facade hiding bitter, conflicted and conceited personalities. This is beauty the American way; quaint family photos hold higher value than a functional marriage and a healthy sex life.

American Beauty is a sardonic portrait of the American dream, a superficial endeavour that disregards personal satisfaction. Lester says midway through the film, “This isn’t life, it’s just stuff,” which is all that American Beauty satirises. The materialistic, reserved projection of success and happiness matters more to Carolyn than living life for pure enjoyment.