Avant-garde is a term used to refer a series of manifestations that openly depart from the canons of the Status Quo. Though the eagerness to innovate can be traced through different stages of history, the emergence of Avant-garde manifestations occurred at the final stage of 19th century.

Those manifestations met a golden age of development as well as periods of decadence and invigorating refreshment through 20th century. As they changed the standard ways of approaching different phenomena, their influence can be traced in our days.

Avant-garde manifestations gravitate under the tense relationship between art and ideology; a space that not always leaves them in a good position. As a consequence, since their development, Avant-garde manifestations have faced the risk of falling in a snobbish discourse about creativity or in a manifest ideology with a lot to say but nothing to produce.

The avant-garde interest in Cinema can be traced in the modernism obsession with photography. If the depiction of reality was Art’s main role, Art was falling short in front of a camera. Though the positions of Avant-garde manifestations at this issue vary, most of them found in photography and especially in Cinema a suitable media to divorce Art from its institutional canons.

The amount of films regarded as Avant-garde is huge. Today, as a term applied to films, Avant-garde is used in a more open sense to refer all movie experimentally produced. Moving through the limits of narrative, time and technique, those movies are a matter of great interest to Cinema students and dilettantes.

The next is a list of twenty Avant-garde films. It doesn’t cover all the big names of Avant-garde Cinema, nor does it take account of all its essential titles. Its intention is merely to work as brief introduction to the richness of Avant-garde Cinema.

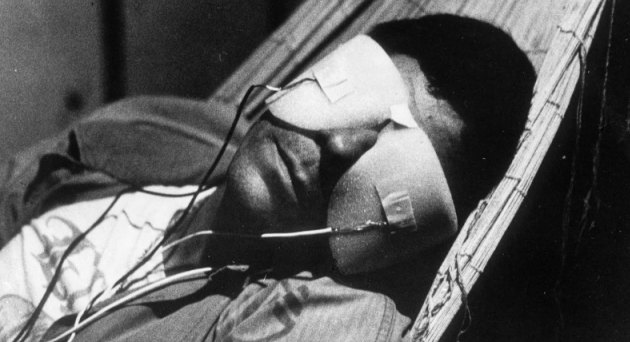

20. Quick Billy (Bruce Baillie, 1971)

Arguably an allegory about the power of change between life and death, Quick Billy is perhaps Bruce Baillie’s most personal work. Filmed in the middle of Baillie’s struggle with the hepatitis that whipped Lou Gottlieb’s Morningstar Ranch, Quick Billy depicts The Tibetan Book of the Death, a mortuary text about the stages crossed by the soul until its renaissance.

Quick Billy is structured in four reels marked by the complex but tasteful supplement relation between visual impoverishment and technical virtuosity; the recourse that made Baillie a groundbreaking figure of the 60’s Avant-garde cinema.

The first three reels constitute an exploration to the stages of death and afterlife. The fourth one, in which Baille’s synthesize not only the film but the vision he pursued from his early works by mocking such exploration, is a kitsch silent Western.

19. Blue (Derek Jarman, 1993)

Derek Jarman’s testament, Blue, is an intimate autobiographical experiment composed by a single shot of a saturated blue screen interwoven by a soundtrack.

Though Blue focuses on its soundtrack, which presents Jarman’s impressions of his life, the film’s hardly elusive blue screen actually works as a symbolic counterpart of Jarman’s melancholic retrospective.

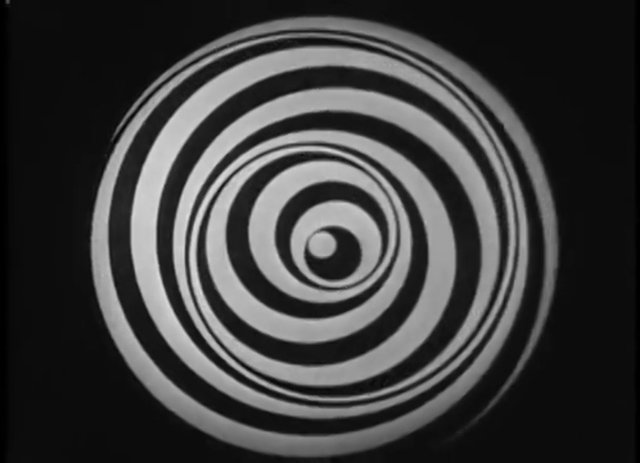

18. Anemic Cinema (Marcel Duchamp, 1926)

An ambiguous but playful exercise from the overall acclaimed genius of Marcel Duchamp, who upon his time escaped from every defining canon including the Avant-garde manifestations themselves, Anemic Cinema is an experimental succession of animated drawings, rotoreliefs as Duchamp fondly called them, alternated with alliterations held by nine revolving disks.

Perhaps there is no better way to describe Anemic Cinema than appealing to its title. Duchamp deliberately weakened the mainstream recourse of the Cinema of his time to arise the viewers’ imagination in order to fulfill their neurotic and widely criticized necessity of unity and completeness.

17. Orpheus (Jean Cocteau, 1950)

Part of Cocteau’s Orphic Trilogy, Orpheus is a surrealist update about Orpheus, the musician that, according to a Greek widespread myth, descended to the underworld in an attempt of bringing his loved one back from the death.

Orpheus is widely respected due to Cocteau’s poetic taste but especially due to the simplicity of the technical means by which he represents the film’s mythical world. For instance, he approaches his shots to show his characters pass into the underworld through mirrors and, running those shot backwards, he carries on their return to life.

The Orphic trilogy is an exploration upon the complexity arisen between artist and his work. Orpheus is the central part of it.

16. Serene Velocity (Ernie Gehr, 1970)

Preserved by The Museum of Modern Art in 2006, Serene Velocity is an algid point in the development of structuralist cinema. The film consists of nothing more than two shots of an office hallway, meticulously carried to explore the spectatorship experience as few films have done.

Serene Velocity entirely lacks of plot, its success lies on its virtuous treatment of movement; a treatment in which some have found a major one about cinematographic ontology.

15. La Jetée (Chris Marker, 1962)

Based upon the film’s narrative context, entirely dependent of a series of still optically printed photographs, Chris Marker referred to La Jetée, an obligated title for sci-fi lovers, as a photo novel.

Departing from a post-apocalyptic plotline, La Jetée follows a few World War Three survivors’ attempts to send a traumatized man back in time to the pre-war world for supplies.

The legacy of La Jetée can be traced from musical video clips to major blockbusters. Its detriment of movement sequences got it a Prix Jean Vigo for short film.