Many African films that remain popular deal with the parallels between Africa’s past in relations to its modern present state. From this, we view a wide range of topics such as traditions, ideological and political institutions that were set by colonizers which remain long after their dissolution, gender roles, and the significance of oral narratives and language.

The films created link the past, present and future of the continent in a way that doesn’t trail the concept of time. Images shown in most the films are a part of a grander story built on layers upon layers of analogies, metaphors and societal events containing many interconnected connotations.

African Cinema as well as other foreign or international films are a tremendous vehicle for enlightenment, education and cultural awareness that some just don’t experience in their lifetime. African films will forever be commemorated as a valuable archive of memory, knowledge and wisdom that is worth preserving, reinterpreted and studied. Here is a procurement of 20 of the best in African films that we recommend you start watching.

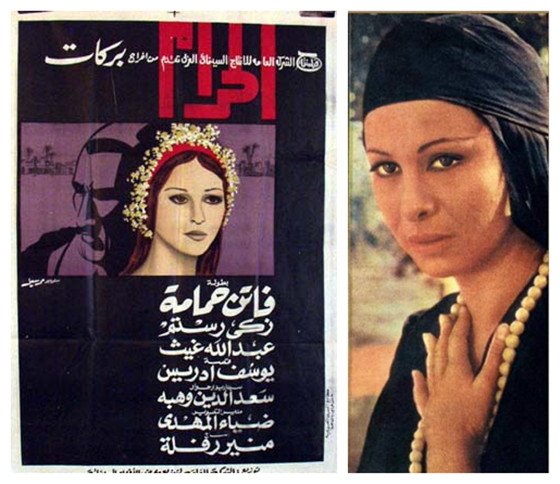

20. El Haram (Burkina Faso, Henry Barakat, 1965)

El Haram (The Sin), widely regarded as the prolific Cairo-born director’s best work, is featured in many of the ten best Arab film lists. It was adapted from a novel by Youssef Idriss, the picture deals with the sufferings of migrant farm workers, whose lives are precarious, since they are hired only by the day at crucial seasons of the year.

The film combines many elements that make up an Egyptian dramatic feature such as a narrative structure using a long central flashback through which the past affects the present. Other ingredients include a pattern of music and images that magnifies the viewer’s emotional response, a general sense of helplessness in the face of an unchanging traditional community.

19. Samba Traoré (Burkina Faso, Idrissa Ouedraogo, 1992)

Idrissa Ouedraogo’s Yam Daabo (1987), in which the child of a peasant family is killed in a traffic accident in the big city, and the same director’s Samba Traoré (1992), is about a prodigal son who returns to the village after having committed armed robbery in the capital. The movie combines the conflicts between tradition and change and the city versus the village into the life of a single character. The quality of life in the city is demonstrated in the rapid violent images that open the film.

It is worth noting, however, that usually the films do not set up tradition and modernity as two irreconcilable poles of an abstract dichotomy. Rather, the subject is depicted as a lived reality in a country whose urban centers form an integral part of global modernity, whereas the vast rural areas still largely adhere to tradition.

18. Finye (Mali, Souleymane Cissé, 1982)

Just as his previous films were created to confront directly the lives of the urban working class, so was Finye, it examines seriously at the workings of power in an African society under military rule. The main characters, two young students live in a world marked by the clash of generations, the pressures of exam-taking in a corrupt educational system, and a mix of commitment and betrayal when their solidarity is tested.

A large portion of this picture is shot with a careful and precisely focused realism and its message is addressed to the present. The director’s social criticism contains memorable symbolic acts, such as the images of innocence and purification at the start and conclusion of the film. His signature style is subtle enough to shift freely into dream sequences or even moments of literal unreality.

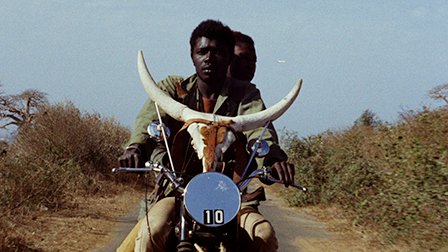

17. Buud Yam (Burkina Faso, Gaston Kaboré, 1997)

Recounts the initiatory journey of a young man in search of his roots. Buud Yam is a sequel to Wend Kuuni (1983), the filmmaker’s first movie and also borrows the same characters.

Kabore’s fourth and perhaps best film, Buud Yam (1996), which won the top prize, the Étalon de Yennenga, at FESPACO in 1997, is a further look at some of Kabore’sfavorite themes: remembrance, identity, the need to be true to oneself. Though village life is depicted as before, with its slow rhythms and parochial concerns, there is a new dynamism, as the protagonist does not just remain to suffer or face defeat. The film contains a lively pace, beginning with the opening sequence of the hero riding intensely through the bush.

16. Ceddo (Senegal, Ousmane Sembène, 1976)

Sembène continues the examination of the African past that he began with Emitai (1971). This time, rather than dealing with a specific historical incident, Sembene exposes the way basic elements of modern Senegalese life are the result of outside intervention. In a period vaguely set in the seventeenth or eighteenth centuries, he exposes the introduction of Islam as an element of exploitation similar to the later colonization of the country by the French.

Sembene also continues to reject the Western film style and instead employs cinematic techniques that convey African traditions. Ceddo investigates the conversion of Africans to Islam at the same time that traditional society is also being approached by Christian missionaries and confronted by slavers.

15. Hyenas (Senegal, Djibril Diop Mambéty, 1992)

A witty, and lovely social critic about men and women. The film details all the sentiments that hails from love and revenge along with a satirical look at consumerism and neocolonialism in Africa. Deals with life outside of a big city, the movie takes place in a backwater village which has seen better days. Hyenas is an adaptation of the play by Friedrich Dürrenmatt, The Visit. In this story a woman who was forced to leave the town, returns to claim her vengeance against the man who was the source of her problems. She has become very wealthy and offers the inhabitants large amount of money if they will kill the man.

In an interview, Mambety was reported stating: “I will make Malaika, the third part of the trilogy about the power of craziness. The first two were Touki-Bouki and Hyènes. Then I will consult God about the state of the world.” Sadly, Diop Mambety, hailed by some as the “African Dionysus,” died of cancer before he was able to complete his trilogy on “human greed and the power of insanity,” which, according to him, have “betrayed African independence for the false hopes of Western materialism.”