When explaining why he dropped out of film school, Paul Thomas Anderson said “My film making education consisted of finding out what filmmakers I liked were watching, then seeing those films. I learned the technical stuff from books and mags…Film school is a complete con, because the information is out there if you want it.”

Whatever one’s motivation, the joy of uncovering the lineage of a favorite director by watching the films that inspired him or her adds another layer of pleasure to the pursuit of excellent movies. To that end, let’s look at the unofficial ancestors: a list of films that influenced great directors.

Martin Scorsese is a film institution unto himself. Within the American context, he is a leading statesman of the art form who gives his name to the cause of film restoration, historic preservation, and getting pictures seen by audiences that would otherwise miss the opportunity.

A tireless advocate for cinema, his interviews are typically warm, enthused, and scholarly without being coldly academic. Internationally, he is known for his iconic gangster films and his encyclopedic knowledge, and application, of film history. With 21 feature films released at the time of this writing, Scorsese has surpassed most of his peers from the New Hollywood era and become the Master of his generation.

Any attempt to limit the film influences on a director of Scorsese’s stature is a fool’s errand. For the sake of demonstrating the dimensions of Scorsese’s reach, let us consider the ten following films and how they inform the sensibility of one of today’s virtuosos of direction and film production. Many of these films were mentioned in the 2012 Sight And Sound Poll where he claimed them to be his all-time favorite films.

However, a favorite film does not always an influence make; for an artist of any medium can adore the work of a predecessor or peer and still produce nothing of any similarity. When considering The Greats of any particular art form, it is inevitable that they cannot draw too directly from their peers but rather steal artfully from the same inspirations. To each personality there will always be some surprises.

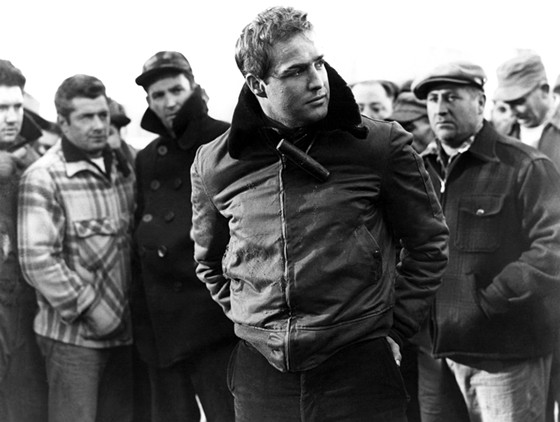

1. On the Waterfront (1954, Elia Kazan)

Marlon Brando plays Terry Malloy, a former boxing contender now working on the docks of Hoboken. When a longshoreman is murdered before he can testify against local mob boss Johnny Friendly (Lee J. Cobb), Terry is convinced to testify in his stead by the dead man’s sister Edie (Eva Marie Saint) and the hardnosed priest Father Barry (Karl Malden).

The situation is more complicated because Johnny Friendly had once persuaded Terry to throw a fight by sending his lawyer, Terry’s older brother Charley (Rod Steiger) to do the persuading. Now Terry needs Charley and his complacent coworkers to support him as he goes against the mob.

On the Waterfront comes at the center of Elia Kazan’s reign as the greatest actor’s director in American cinema. On either end of this film are 1951’s A Streetcar Named Desire, Marlon Brando’s breakout role already honed from the Broadway play of the same name, and 1955’s East of Eden, which introduced James Dean to the world.

As the leading proponent of Method Acting, Elia Kazan took what could have been a middling tale of local corruption and turned it into a monumental story. Brando’s performance is rightly remembered for articulating something grandly mythic about the individual’s ultimate loyalty to his self-respect. In 1954, On the Waterfront took the heroism of the western and brought it back east where it hit little Marty S. smack on the nose.

The protagonist of a Scorsese film is usually working class but not always. Sometimes they are from some means but “temporarily embarrassed” by their financial situation. The true poverty suffered by a Scorsese protagonist is spiritual in nature. They are consumed by greed, or guilt, or loss, or paranoia. Whatever it might be, there is a crisis of confidence plaguing them. And this is a legacy of On the Waterfront.

Terry is strong and the mob is not immortal, but what truly is at stake for him is the cost of reclaiming his self-respect, which Johnny Friendly stole by ordering him to throw the fight that would have been his chance at the title. Viewed from these terms, the ending to On the Waterfront is a glorious reclamation. Unlike our next film.

2. Ashes and Diamonds (1958, Andrzej Wajda)

In May, 1945, the Nazis has just surrendered but the war is not over in Poland. The power vacuum left by the German soldiers compels the various factions of the resistance and the Russian-backed communists to sort out whose Poland it will be. Two Home Army soldiers (Zbigniew Cybulski and Adam Pawlikowski) are ordered to assassinate the local commissar (Waclaw Zastrzezynsky). The commissar is in the town searching for his son who had been living with a right-winger aunt and got himself imprisoned by the Red Army.

One of the Home Army assassins, Maciek, strikes up a relationship with a barmaid while waiting to catch the commissar. As he falls in love, he is confronted with a moral dilemma around his orders and the reasons he’s been fighting. Because it is a Polish story, don’t expect a happy ending. As Scorsese told National Public Radio, “there’s a strong tragic sense in Polish cinema, but it seems to be in balance with very, very strong strains of a spiritual resilience and also a dark comedy.”

Although “Popiół i Diament” is one of the greatest examples of Polish post-war cinema, it takes a few cues from Hollywood. The characterization of Maciek was deliberately styled after James Dean, and his scenes with the barmaid Krystyna (Ewa Krzyżewska) were based on Marlon Brando’s scenes with barmaid Kathie (Mary Murphy) in The Wild One. But the love that binds this film to our list is Scorsese’s. It was a college romance marked by the vivid cinematography that expressed more than the image could hold and the acting that carried an immediacy that remains fresh to this day.

He says, “It’s important that we look at all national cinemas outside our own…knowing other cinematic cultures gives you a new sense, or renewed sense, of the cinematic culture in your own country. And you see it in a new light. It enriches it.”

Taken in contrast to the American expectations that were company code in the 1950s, Ashes and Diamonds is earth-shattering tragedy. The sense of total loss amid black humor and spiritual resilience would be an ideal Martin Scorsese would bring to his own work.

3. The Searchers (1956, John Ford)

In John Ford’s 115th feature film, Ethan Edwards (John Wayne) returns from the Civil War to find that the members of his brother’s family have been killed or abducted by a war band of Comanche led by a warrior named Scar. Ethan Edwards decides to travel deep into Comanche territory to rescue his surviving relatives and bring them home. The rescue mission turns sideways when, after five years of searching, he learns that his niece Debbie (Natalie Wood) has become a Comanche wife.

John Ford had already a Best Director Oscar four times when filming began on The Searchers, and while his legacy today is firmly within the Western genre and as a mythmaker of the Old West, it was his social commentary films that received the most praise at the time. The Searchers changed all that by a combination of the landscape framing already mastered over many other films shot in the same environment but this time in stunning Vistavision, and the more visceral, ugly motivations of John Wayne’s Ethan Edwards.

Martin Scorsese vividly remembers going to see The Searchers with his friends after the last day of parochial school. He had by this time figured out that when the names John Ford and John Wayne were listed together, it was likely to be something worth seeing. But this was not the John Wayne character of the past. “He’s absolutely terrifying”. Ethan Edwards’ hate is so strong, he hates the native people beyond the grave. He would deny a dead Comanche the repose promised by his cosmology by desecrating his corpse!

Scorsese has admitted that The Searchers makes him uncomfortable but he avows that, “In truly great films — the ones that people need to make, the ones that start speaking through them, the ones that keep moving into territory that is more and more unfathomable and uncomfortable — nothing’s ever simple or neatly resolved.”

This is not the only aspect of The Searchers that makes it controversial by today’s standards. The racism is both textual and subtextual in the unenlightened manner of a 50s film, and the humor is distinctly Irish, and outré today. However, it would be disingenuous to reject a film for bringing to surface what was already a disturbing issue.

In the repressed era of the 1950s, Ethan Edwards expressed the racism that was everywhere; like the rage of the 1970s when Scorsese was making Taxi Driver, DeNiro’s Travis Bickle and John Wayne’s Ethan Edwards cross the line and act out the dark urges of their times.

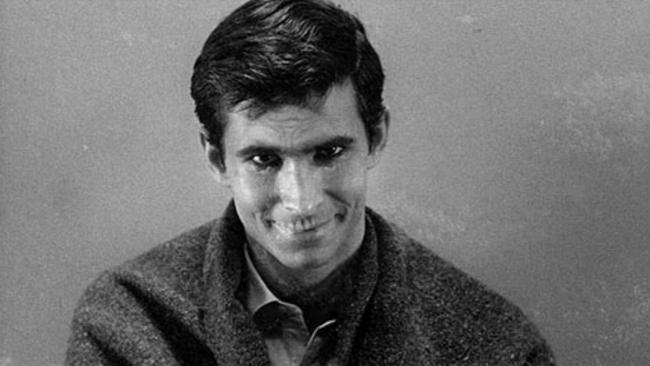

4. Psycho (1960, Alfred Hitchcock)

In a spur of the moment decision, Marion Crane (Janet Leigh) decides to leave Phoenix with the $40,000 her boss entrusted to her to deposit at the bank. She wants to marry her boyfriend, a divorcee whose finances are tied up in alimony. Getting to Fairvale, California is a long drive and after having spent a night in her car, she decides to spend her second night at the Bates Motel, managed by Norman Bates, a taciturn and solitary young man who seems to be dominated by his mother.

In a radical break of story norms, Marion ceases to be…our protagonist. Her sister recruits a private detective and Marion’s boyfriend to search for Marion and eventually they discover what is really happening at the Bates Motel.

Like many audience goers at the time, Scorsese was taken in by the expectation that despite the music and the foreboding tone of Marion’s predicament she would continue to be the main character of the film. The shock of audience expectations hyped Psycho’s release and made it one of the first films that could be spoiled by loose lipped patrons walking out of the theatre while a line of people wait to get in.

The violence was considered beyond acceptability by many people. It doesn’t matter that not bodily harm was actually portrayed on screen. The graphic editing made it all the more insidious. We see lessons in graphic editing brilliantly on display in Psycho, and in the ring of Raging Bull, the ending to Taxi Driver, various scenes in Goodfellas and The Departed.

Scorsese has a reputation for violence but along with violence he deploys language beyond what many consider acceptable. In Casino, the word “fuck” is heard 398 times. In Goodfellas it is 300 times, and The Departed uses that most malleable of English epithets 237 times.

5. The Leopard (1963, Luchino Visconti)

Il Gattopardo is the lush adaptation of the classic novel by Giuseppe Tomasi di Lampedusa, detailing the decline of the aristocracy amid Italian Unification in 1860. The family in focus is the Sicilian Salinas, whose patriarch Prince Don Fabrizio Salina (Burt Lancaster) is the famous Leopard of the film’s title. He is proud but ultimately pragmatic when he allows his nephew Tancredi (Alan Delon) to marry Angelica (Claudia Cardinale).

Angelica’s father is the bourgeois Don Calogero, exemplar of the new ruling class. Don Calogero hasn’t the nobility of The Leopard, just as The Leopard’s nephew is not the war hero he claims to be, but both families must adapt to the sweeping social changes to maintain their power if not their way of life.

Visconti was a founder of Neorealism, which emphasizes class struggle from the shorter end of the stick with minimal embellishment, but with Il Gattopardo he went a different direction. As the aristocrats maneuver to stay relevant in a changing world, it is the film’s mission to celebrate the detail in mise-en-scene. This includes a previously unheard Verdi waltz, majestic costumes, and a slow and studied 45 minute ball room scene.

The overall effect is not the sort of fast and slick storytelling one expects from Martin Scorsese, but you can see how he aspires to present worlds that can be lived in as the plot unfolds. And he certainly attempted the same thing with The Age of Innocence in 1993. When Scorsese reintroduced The Leopard to the audience at Cannes where it had won the Palm D’Or in 1963, he said “I live with this film everyday of my life.”