When explaining why he dropped out of film school, Paul Thomas Anderson said “My film making education consisted of finding out what filmmakers I liked were watching, then seeing those films. I learned the technical stuff from books and mags…Film school is a complete con, because the information is out there if you want it.”

Whatever one’s motivation, the joy of uncovering the lineage of a favorite director by watching the films that inspired him or her adds another layer of pleasure to the pursuit of excellent movies. To that end, let’s look at the unofficial ancestors: a list of films that influenced great directors.

Christopher Nolan makes blockbusters with the loving obsession of an auteurist director held close to the bosom of the cinaphilic community. His 9 feature films track an increasingly expansive canvas of human endeavor: from the tight, paranoid, neo-noir calling-card to the movie business that was 1998’s Following, to this year’s $165 million dollar, 169 minute long space epic, Interstellar.

Unlike many contemporary film directors adapting to a business model that runs on self-promotion, Christopher Nolan does not enjoy discussing his films and he refuses to talk about his family life. The portrait assembled from interviews with his collaborators and the instances where he discusses other directors’ work suggests a personality driven to perfection, emanating calm control. These ten films provide us with clues as to where Nolan’s understanding of cinema perfection originates.

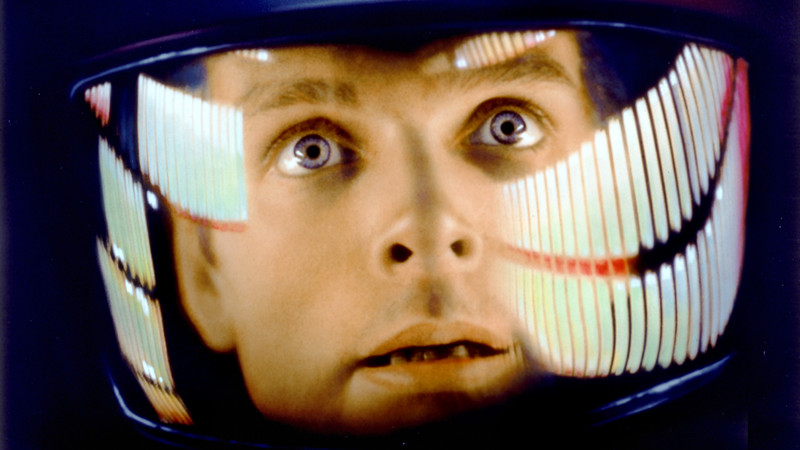

1. 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968, Stanley Kubrick)

Stanley Kubrick’s space epic begins at the inception of humanness: when one monkey beats its competitor with the aid of a bone. In the iconic jump-cut for the ages, the bone is replaced with a spaceship floating through the galaxy. What follows is a story of humanity and fate…at least that’s how some people have interpreted it. 2001 is a movie experience, more than a story.

For Christopher Nolan, this is the rosebud of a brilliantly flowering career. “I saw 2001 when I was about seven years old. They re-released it after Star Wars so my dad took me and my brother to see it at the Odeon Leicester Square on the huge screen. It was just a mind-blowing experience and I’ve been a huge Kubrick fan ever since. All my friends at the time saw it and loved it; we didn’t understand it, but we used to argue about what it meant. It just has that sensory stimulation of pure cinema that speaks to people of all ages.” (quoted from Empire Magazine)

Hallmarks of Christopher Nolan’s cinema passion are in the above quote. The huge screen suggests his future championing of IMAX and the continuance of film in the digital age. The mind-blowing experience suggests his own use of non-linear storytelling to wow audiences. The suggestion that all ages respond to the “sensory stimulation of pure cinema” could be the declaration of an ideal. For however personal the film might be for Christopher Nolan as a person, his loyalty is to the audience and to the purity of experience in a film story.

Memento and Inception have been criticized for being too complicated to understand. Critics of the Batman trilogy have taken umbrage with relocating Gotham to Chicago, and with the editing of action sequences. Interstellar is the first of Mr. Nolan’s 9 feature films to have significant screen time devoted to the emotional response of characters to events.

No doubt these movies are not flawless, but they are reaching for an ideal. Pure cinema for Christopher Nolan must dazzle while it thinks. An individual filmgoer’s understanding of the story is beneath the priority of giving the audience as a whole an experience similar to watching Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey.

2. The Testament of Dr. Mabuse (1933, Fritz Lang)

A wave of crime plagues the city and the evidence points to the criminal mastermind of Dr. Mabuse, but he has been imprisoned in a mental asylum for ten years. A conspiracy is revealed and an obsession leads to a pathetic end. On the Criterion website Christopher Nolan calls this, “Essential research for anyone attempting to write a supervillain.”

Fritz Lang revived the character of Dr. Mabuse from one of his earlier silent-era projects to tell an exciting tale of brutality, conspiracy, and corruption in modern Germany. It has been supposed that the rise of Nazism was not coincident to the director’s intentions, especially when Hitler’s Minister of Propaganda banned it.

Fritz Lang dramatized the anxieties with technology and industrialism for 20th century audiences. The dream of progress quickly becomes the nightmare of oppression when considering the nefarious power of brilliant, immoral minds. For Christopher Nolan and his 21st century audiences, that anxiety has transferred to the realm of privacy and the threat of terrorism.

Dr. Mabuse might be the hypnotist exerting influence upon the will of dangerous men, but the Joker needs no willing minds to influence. He can construct situations that surface latent antipathies, egotisms, dark tendencies. Both super villains relish the collapse of civilization, law and order.

More prevalent in the whole of Christopher Nolan’s filmography is the power of obsession. The true instigator of the crime wave in The Testament of Dr. Mabuse is the victim of an obsession. Like the struggling writer in Following, he acts out of impulse, against his better judgment, and to his ultimate demise.

In Memento, Leonard (Guy Pearce) is tracking down the man who raped and murdered his wife despite an inability to form new short-term memories. His obsession with justice is, like Bruce Wayne’s, born out of a personal grievance and fueled by that trauma. The rival magicians in The Prestige are obsessed with besting each other’s dedication to the art of illusions.

The destructive and awe-inspiring power of obsession: a mental state that can produce profound effects on the external world through the sheer doggedness of the Obsessive’s focus. It’s the true power of a master magician tirelessly working at his tricks. It is the compass at the center of a moral character’s integrity, and it is a pretty valuable trait to have as a director. Perhaps this summarizes Christopher Nolan protagonists’ distinction from the other characters, and Christopher Nolan among his peers.

3. The Usual Suspects (1995, Bryan Singer)

The film event at the end of Christopher Nolan’s college years, The Usual Suspects made a Hollywood darling of director Bryan Singer, who like Nolan took control of a superhero franchise. The story takes off with a massive explosion ripping through a ship at harbor in a San Pedro, CA. Along with casualties there is 91 million dollars’ worth of cocaine missing.

Detective Dave Kujan (Chazz Palminteri) interrogates the only witness and key suspect, “Verbal” Kint (Kevin Spacey). In a series of dizzying flashbacks, Verbal spins the tale of his group of thieves and their contact with the mysterious arch-crime lord Keyser Soze.

Keyser Soze is no diabolical mentalist like Dr. Mabuse, but his enigmatic influence is the prime mystery tickling audience, including the detective. The Usual Suspects hinges on a twist ending, one that astounds audiences while disappointing their expectations in a way similar to the endings of The Prestige and Inception.

The added value of influence on Christopher Nolan’s particular brand of neo-noir fiction is the way flashbacks and twists give the audience information strategically. The story goes backwards as it goes forwards, much like Memento. Audience memory is tested while acts of faulty memory recall become essential turns in the mystery. The result is a noir-ish retread that shifts the narrative tension from the traditional “what will happen” to “what will have happened if…”

4. The Manchurian Candidate (1962, John Frankenheimer)

Another thriller leveraging the flaws of memory from hypnotism. This time the conspiracy is political. Gore Vidal once suggested that the Kennedy assassination launched the Cold War paranoid political thriller genre into the popular consciousness. This film predated the assassination, but just barely. Rumor spread that The Manchurian Candidate’s release was curtailed out of respect to the departed. It was actually a disagreement between Sinatra’s people and the studio over revenue distribution.

A celebrated Korean vet (Laurence Harvey) has been brainwashed by the Communists to assassinate persons deemed obstructive to their subversion of America and the free world. The operative agent in control is the man’s own mother (Angela Lansbury). His old army buddy (Frank Sinatra) is also responsible for uncovering the conspiracy before the henpecked step-father is planted to get elected President. Freudian family dynamics blend with Red Scare anxieties seamlessly in this paranoid tragedy.

Technically, the wit of the story is matched by the composition of shots and the cinematic shorthand that efficiently depth of character. For example, one political family uses Abraham Lincoln as a decorative motif while the rival’s home is decked out in eagles and bunting.

The first is quaint, almost folksy, and by comparison to the symbolic bluster of abstraction favored by the latter, it is specific as to which America they align with. It’s also an adroit satire on the American bombast en vogue at the time. Senator Joe McCarthy was dead and disgraced by that time, but his hysterical denouncement of communists in every branch of the government was still believed by some.

Inception’s approach to brainwashing is more compelling today than the mid-century fascination with Oedipal complexes, but the plot exploits the same paranoid suspicion that one’s thoughts are not one’s own. That the privacy of one’s inner life and the sanctity of one’s will is not an impenetrable fortress, but rather a complex of symbolic mechanisms capable of manipulation.

The process of simplifying the foreign concept to critical impact and receiver acceptability should bring to mind the work of Saatchi & Saatchi, the advertising kingpins that put Margaret Thatcher’s Tory party in power with “Labour isn’t working” and who developed the one-word message technique now used by corporations—Priceless— political campaigns—Hope, Forward—and even movies, like Inception. Or Following. Or Memento. Or Interstellar.

5. The Thin Red Line (1998, Terence Malick)

It’s 1942 and the US Army is fighting a bloody offensive north through the island of Guadalcanal. Japanese resistance is stiff, desperate, and both sides experience inhuman acts of violence. The scale is not historical but mythical. The Thin Red Line aspires to be an epic writ in the lyric of Malick’s coolly observant camera and metaphysical sensibility. The battle gains specificity by following the lives of a group of soldiers in C—Company over a period of a couple of weeks. Frequent Nolan collaborator Hans Zimmer also composed the score for The Thin Red Line.

Christopher Nolan has said of The Thin Red Line, “It’s one of the few films I’ve seen that, even though it’s based on a book, could only really be done in cinema. It’s just the essence of cinematic storytelling. It has a hypnotic quality where the viewer’s relationship with the photography, and the sound particularly, creates narrative points; it creates emotions that drive the narrative.

These things are created by the combination of picture and sound rather than the dialogue. A lot of films, a lot of great films in fact, could also be radio plays or television programmes or stage plays. The Thin Red Line is pure cinematic storytelling.”

The book from which the movie is loosely adapted has all the trappings of mid-century Americana. The urge to create an American mythos out of the senseless bloodletting on a remote Pacific Island requires some very stiff characters with the philosophical breadth of either fatalism or existentialism. This is good country for humorless white men inspired by warrior culture. The movie suppresses the homosexual awakening of one character and makes the Jewish captain into a Greek.

Nolan’s territory is reflected in the relationship—or Socratic dialog—between Sergeant Welsh and Private Witt. Welsh (Sean Penn) believes there is no other world than the one he senses and knows. He reduces war to a disagreement over property and human life to meat. Private Witt (Jim Caviezel) believes that there are other worlds, other ways, and his eventual sacrifice can be taken as a leap of faith that the individual is illusory and the whole of people is the true life lived.

Compare that to the ineffable mystery in Interstellar and we might have a glimpse at where Christopher Nolan’s ambitions are taking him. The sci-fi adventure is a big change from the neo-noir territory of Following, Memento, Insomnia, and his take on the Batman mythos. Inception introduced a sci-fi element to his film work but Interstellar is something entirely different and extremely ambitious.