6. Mysterious Objects at Noon (2000)

Mysterious Object at Noon was shot in 1997 on 16mm film, released in 2000 after a difficult editing process, and then blown up to 35mm during restoration. Martin Scorsese includes it as part of his World Cinema Project. For those who like to compartmentalize their films into genre, the methodology of director Apichatpong Weerasethakul places the film within the parameters of Cinéma Vérité

Crooked alleys and car door fish markets, classrooms and laundromats, these places are only a small inventory of the myriad locations that the camera explores. It threads together people’s meager material existence to form a cultural object representative of the quotidian pleasures of children and struggles of adults. The treatment of everyday happenings has little interest in criticizing, aiming to assemble and present life in Thailand as it existed at the turn of the 21st century.

Meditative scenes of the passing landscape also create a sense of movement that weaves road movie elements into the social fabric on display. Streetcars traveling between the province and Bangkok reverberate from the steel tracks and bustling wind, drowning out the conversations of feuding passengers. What they are saying is unimportant. The image of strife is enough to make the conflict between the rural and the urban clear.

7. The Bridge (1959)

An antiwar film from Bernhard Wicki that was the first of its kind to be released in post-war Germany, which was still coming to grips with its guilt and shame for the Nazi evil that possessed it. At a time when Germans could no longer tell their stories, this film dares to look at the complicated lives of Germans in the last month of the war, realizing the tyranny that misled them. This realization did not however come so quickly to the Hitler Youth.

In a provincial town, a circle of teenage friends each receives an order of conscription much to their pleasure and excitement. Their parents, knowing the war is lost, some of whom are maimed from their time on the front, struggle to accept the doomed fate of their children. The fanatical misconceptions of the patriotic adolescents who are too inexperienced to handle a weapon, let alone know they are marching off to certain death, satirizes the generational conflict that arose between Germany’s brainwashed youth and their disillusioned parents.

The gruesome violence that erupts in the film’s climax criticizes how the Nazis exploited the innocence of its youth, perceiving them as merely another cog in the war machine. In the moments before death, the world-shattering realization sets in that there is nothing honorable about dying for a cause that treats its defenders less than human. Yet for some characters, impending death does not shake their beliefs. Collectively the moral development of the characters is ambivalent, as some abandon their convictions while in others they harden.

The black and white cinematography creates an apocalyptic smoke that pervades during the night as the children callously prepare for battle. When day breaks, the ghastly fog gives way to the black smoke of exploding ammunition and burning corpses. As the film turns its concentration to the image of the bridge in its final scene, it becomes clear that the titular metaphor symbolizes the severed link between young and old.

Compared to Rossellini’s Berlin, Year Zero, The Bridge is truer in its realism and more harrowing in its fatalism. Not surprisingly, the film’s anti-fascist stance was misunderstood upon release.

8. The Fabulous Baron Munchausen (1962)

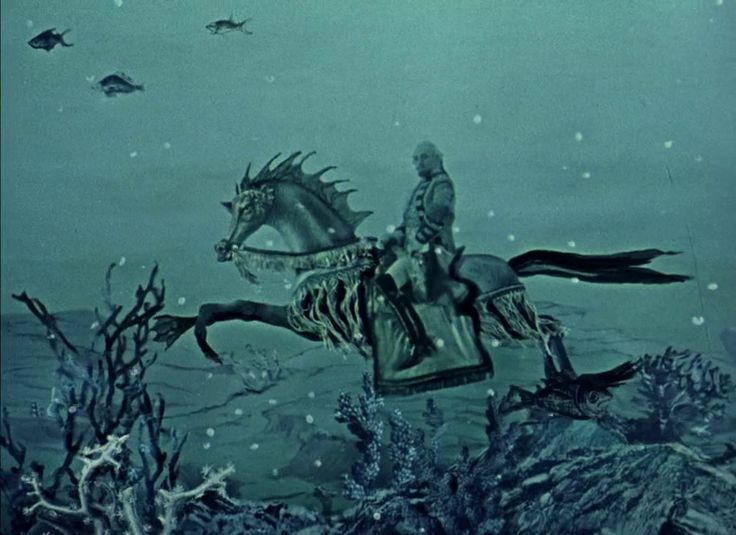

To this day, few films rival the fantastical artistry of Karel Zeman’s The Fabulous Baron Munchausen. Fusing animated backgrounds and props with live-action characters, the imaginative nature of the visuals and scenarios live up to the reputation of the 18th-century German fables that the story and titular protagonist are based on.

In comparison to contemporary animated films, Zeman designed the practical effects himself according to thorough research, giving the film an authenticity and painterly quality that leaves a strong trace of his human touch. The deliberate choice of every detail in the film is also apparent. While the plot revels in fantasy, spanning landscapes that include the surface of the moon and the inside of a whale’s belly, Zeman doesn’t bombard the audience with pointless overuse and oversaturation of color. In Zeman’s words, he uses color sparingly like a painter who adds only what is necessary.

Like literature that disguises itself as a children’s book, but leverages its use of fantasy to speak about mature themes, The Fabulous Baron Munchausen does the same. It is a celebration of the spirit of discovery and the limitless potential of the human imagination.

9. The Official Story (1985)

Lead actress Norma Aleandro gives a rapturous performance as Alicia, the wife of a corrupt Argentinian bureaucrat, which is well-deserving of attention, and earning her the best actress award at Cannes in 1985. Alicia is also a rigorous history teacher whose passion for the truth sends her in search of her adoptive daughter’s origins. Her quest pierces the middle-class sphere that protects her from the riotous streets of San Diego that has become a battleground for the lower classes protesting against the totalitarian government, demanding the locations and fate of those lost to a government purge be revealed.

At the heart of this social satire is a family melodrama. Alicia’s concern for her daughter, those the government has trampled underfoot, and skepticism about the indirect effect of her complacency as the wife of a bureaucrat has had on the victims of genocide, clashes with her husband who serves the aims of the regime he works for. Behind closed doors, as the couple’s marriage starts to fray, the vehemence of Roberto to protect the awful truth about how the family came to adopt Gabby reaches incendiary levels. Like those pleading for their loved ones in the street, Alicia’s insistent probing of her husband culminates in a violent response. Their marriage becomes an allegory of destructive government oppression during Argentina’s “Dirty War”.

10. The Vanishing (1988)

According to Stanley Kubrick, director George Sulzier’s The Vanishing was one of the scariest movies Kubrick had ever seen. Praise from one of cinema’s titans carries a lot of weight, planting big expectations in viewers’ minds, most of which will be exceeded from the movie’s suspense building, yet unconventional structure, and it’s horrifically shocking ending.

The plot focuses on the disappearance of a Dutch woman, Eva, whose husband Charles, after investigating her case for three years, cannot move on with his life until he knows the fate of his late wife. Similar to how Psycho kills its leading lady halfway through the film, Johanna ter Steege who plays Eva, appears in the film for only eleven minutes. Nonetheless, her spirit haunts the rest of the film because of Charles’s obsession with uncovering the events of her murder.

Sulzier carves a new path again, shifting focus to the killer part-way through the film. He connects the mystery of Eva’s vanishing with a psycho-analysis of the film’s villain. The disturbing details of this plot thread do not become apparent until the film’s final sequence when the audience realizes that it reveals the killer’s motives, methodology, and philosophy. Sulzier pulls off an impossible trick. He shares all the information necessary to solve the mystery, but doesn’t break the enigma of the antagonist and the plot, until what happens to Eva is shown and everything comes into grim focus.