6. L’Age d’Or (1930, Luis Bunuel)

Director Luis Bunuel became the hero of satirical surrealism with L’Age d’Or, but it came at a merciless cost. Right wing and clerical authorities condemned the film, creating much notoriety for Bunuel. The controversy eventually proved to be a shattered mirror that marred part of Bunuel’s storied career in bad luck, labelling him as too incendiary and therefore too risky to hire.

People still talk about Bunuel’s first feature, An Andalusian Dog, like it happened in our lifetime, for the moment he sliced open an eyeball, it spun the art world wildly off its axis, and its dizzying effect is still turning heads. The underground surrealists of the time inaugurated Bunuel into their circle with that film’s release, but L’Age d’Or has a stronger thrust of the absurdist critiques of Catholicism and the bourgeoisie definitive of the director’s mature period.

There is a vehemence in the imagery that was too crude for the older Bunuel. But it’s this youthful passion of a director who knows he is one of the first to grasp this new visionary expression by the tail, wanting to discover in what ways he can twist and turn it, that still makes the film a pleasure and a wonder to watch 90 years after the inferno it ignited upon its release.

7. Ratcatcher (1999, Lynne Ramsay)

From the landfilled projects of Glasgow emerges the heartbreaking debut feature of Scottish director Lynne Ramsay. James blames himself for his friend’s drowning accident. As he navigates the hardships of living with his guilt and his alcoholic father on the shabby margins of Glasgow, he realizes escape is his only way out.

The backdrop of atrocious poverty sets the stage for the wretched youth who live there and the broken homes they are a part of. These three pillars of the city outskirts, individual struggle, and family dynamics return over ten years later in We Need to Talk About Kevin.

Rather than follow the perspective of the son, the latter film focuses on the mother. The lives of the characters as middle class Americans are also worlds apart from those in Ratcatcher’s bleak housing projects, or at least on the surface. But the gloomy overcast that colors Glasgow also shades Eva’s suburban home, characterizing the impoverished relationship she has with her son and the fading love of her formerly happy marriage.

Ramsay is also known for telling her stories through the use of enigmatic images, and both films fade in on white window curtains, that while not certain in meaning, are nonetheless unsettling and foreboding. Ratcatcher establishes Ramsay’s fascinations, concerns, and how she likes to show them. The diverse scenarios Ramsay uses to articulate the comparable anxieties of her characters is a testament to her skill as a director.

8. The 39 Steps (1935, Alfred Hitchcock)

The film that gave birth to the MacGuffin. Many of Alfred Hitchcock’s suspense thrillers over the following quarter century would employ this plot device to embroil its protagonist in the film’s action.

In the case of The 39 Steps, Richard Hannay catches wind of a conspiracy against the British military that has something to do with “the 39 steps.” His possession of this information establishes him as the target of a chase spanning across England and into the Scottish Highlands, fleeing for his life but also to unlock the nefarious secret behind the mysterious phrase.

There are two defining features of the MacGuffin plot device: it sets the plot in motion as already mentioned, but it is also becomes an extraneous after-thought, never being uncovered, and having no bearing on the actual conclusion of the film. It is the hook that catches the audiences’ attention, but which Hitchcock then replaces with the more pertinent concern of the protagonist’s survival. The most famous example of the MacGuffin plot is undeniably North by Northwest. It similarly follows its lead character around the United States in search of a MacGuffin that eventually puts his life in peril, surreptitiously erasing the MacGuffin out of everyone’s memory.

9. The Magnificent Ambersons (1942, Orson Welles)

Even if you are only in the fetal period of your cinephilia, there is little doubt that you have heard or seen Orson Welles’ Citizen Kane. Among many other things, the film is famous for having assembled the prevailing film techniques and styles into a single picture, representing how far filmmaking had advanced up to 1941. Whether the film is the best representative of Welle’s filmography is debatable.

His follow-up feature, The Magnificent Ambersons, although a mutilated cut from Welles’ original vision, is still worth seeing for the high contrast black and white that audiences fondly remember him for. The film satirizes the rise of the auto industry through following the downfall of the wealthy Amberson family, particularly the wasteful matriarch and bungling son, Fanny and George. Most of the film takes place in the mise-en-scène of their luxurious family home, filled with shadowy abyssal corners that characters walk out of to enter the scene, and stark lighting that elevates the melodrama. As the situation spirals out of control, the lives of the Ambersons literally and figuratively begin to darken.

Welles’ dramatic lighting and strikingly intense contrast values ink his signature onto his films. His adaptation of Franz Kafka’s The Trial, the plutonian expressionism of his Macbeth, or the sooty debauchery and betrayal in Chimes at Midnight, are immediately recognizable as Welles’ films for how they exploit the dramaturgy of black and white.

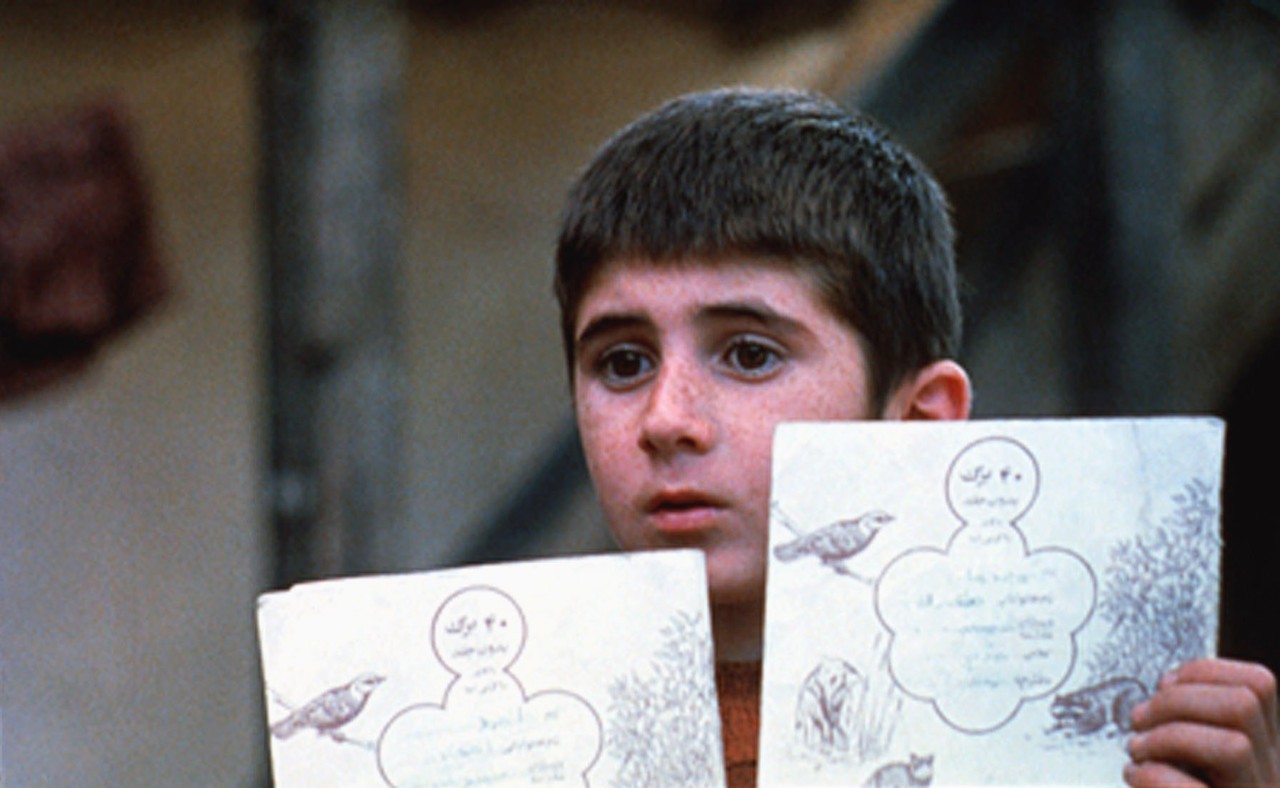

10. Where Is the Friend’s Home? (1987, Abbas Kiarostami)

An early entry from the internationally renowned Abbas Kiarostami, and the first of the Koker-Trilogy, lays the blueprint for much of the famed director’s later work. The plot is simple. In a rural Iranian village, young Ahmed travels back and forth on foot to a neighboring village in search of his friend, wanting to return his notebook so their teacher does no expel him the next day.

Simplicity is also the language of intimacy for Kiarostami, who looks deep into this deceptively banal situation to reveal the abundance of life churning there. Although the three dramatic unities of Aristotle are a western idea that Kiarostami may not have been thinking of, he nonetheless follows them here, and would continue to do so throughout his career. Kiarostami observes the daily duties of country life and then mirrors those with the burden of generosity and friendship, generational and familial divides.

For anyone familiar with Kiarostami’s Palme d’Or winning feature Taste of Cherry, Ahmed’s continuous wandering over repetitive landscapes and street allies in search of a friend who can help him return his classmate’s notebook, will also be reminded of Badii’s labyrinthine journey through the desolate outskirts of Tehran, who like Ahmed, is in dire need of a friend’s compassion.