6. 8 ½ (1963) – Federico Fellini

The levels of analysis and interpretation of this masterpiece included critiques on modern society, the struggles of creativity, Catholicism, Freud, women, memories, fantasies, dreams, illusions and allusion, but it all boils down to one subject: Fellini himself.

Where could Fellini go after rocking the cinematic world with “La Dolce Vita”? He had to go deep inside himself to reveal his childhood flashbacks of the town prostitute dancing on the beach, to the fantasy of being a Roman figure whipping the people in his life. And on the contrary, it reveals what was happening outside of his life, such as the pressures of creating another masterpiece and the affairs and encounters with the numerous women in his life.

No creative or technical choice in this film is out of place or doesn’t exceed new heights of filmmaking. Fellini was working with his closest collaborators, from Marcello Mastroianni to Gianni Di Venanzo to Nino Rota. He was creating the circus of his mind and life with people he trusts to bring his life to the screen.

Many Fellini films have been personal, such as drawing from the small town life in “I Vitelloni,” to working with his wife Giulietta Masina in “La Strada,” to “Fred and Ginger.” But with “8 ½,” almost any cinephile or film watcher can see that this film was born straight from the artist’s own life.

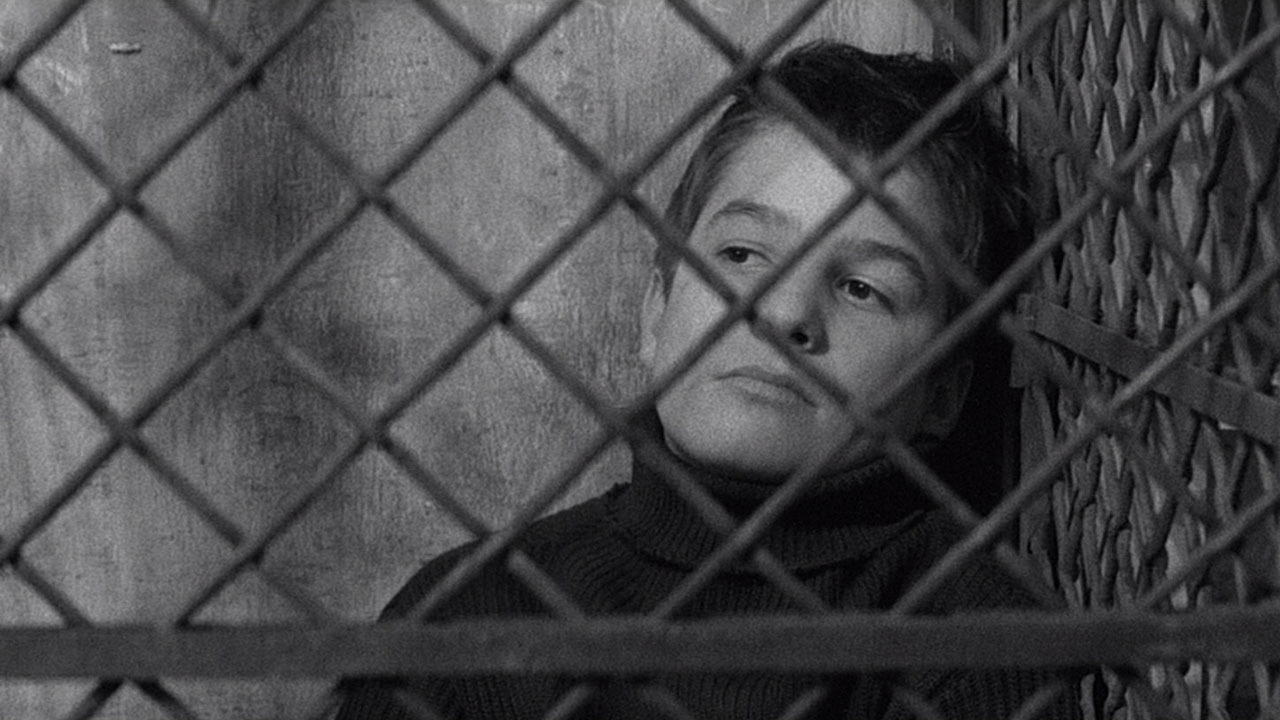

7. The 400 Blows (1959) – François Truffaut

No better way to kick off one of the most important film movements of all time, the French New Wave, than a film straight from the director’s life. Francois Truffaut’s masterpiece displays the adolescent Antoine Doinel, played by the one and only Jean-Pierre Leaud.

The film is semi-autobiographical as it tells a decent amount of Truffaut’s life as a teenager from the dealings with his parents, the law, and society. The film is also a love letter to the French cinema that inspired him to grow from a critic of filmmakers, such as Jean Vigo and Andre Bazin.

One out of many examples in this film is that Truffaut stole a typewriter, only to return it shortly afterward and get caught in the process. This very incident is directly shown in the film. Truffaut drew heavily from his own life and experiences working in Cahiers du Cinema.

Therefore, from intense cinematic criticism, observation, and obsession, and a rich and turbulent life up to age 27 (when he made the film), he was able to create a deeply personal film with cinematic means. Truffaut knew how to express his desires, faults, loves, and hates in his debut feature.

Truffaut continued to explore Antoine Doinel until 1979, often drawing from personal situations ranging from love affairs, military experience, and the ordinary encounters on the street. However, with this film, the perfect doppelgänger of cinema was born.

8. Mean Streets (1973) – Martin Scorsese

After the low-budget first feature “Who’s That Knocking at My Door” and the exploitation film “Boxcar Bertha,” Martin Scorsese made something more personal from the recommendation of John Cassavetes. Therefore, Scorsese turned to his life in Little Italy and the relationship between his father and uncle.

Most of the film was composed of the life that Scorsese saw when he was growing up. Therefore, he went to his go-to actor, Harvey Keitel, and soon to be go-to actor, Robert De Niro, to create two authentic Italian New Yorkers hustling to make a living, being good Catholics, and maintaining their ever-struggling relationships.

You can see the intricate details of the exchanges between Keitel and De Niro that these were witnessed firsthand. Almost like a documentary approach that reveals the authenticity of the lifestyle and neighborhood.

The film is a staple of personal, independent filmmaking and especially coming out of the Hollywood New Wave, stands even more relevant. The film was the starting point for Scorsese that would obsess his life and career such as sin, guilt, redemption, violence, and family. A majority of his cinematic themes can be traced back to this film, showing how deeply personal the film and world of “Mean Streets” is to him.

9. Still Walking (2008) – Hirokazu Kore-eda

Hirokazu Kore-eda focuses on family structure, relationships, death, and dynamics for a large number of his films. In “Still Walking,” the family gathers on the anniversary of the death of the oldest son, Junpei. As one may assume, issues around the family are brought up, but only Kore-eda is able to portray the generational divide, points of view, and the underlying subtext of every exchange so humane and tenderly.

The film doesn’t have your typical American-style shouting matches; Kore-eda’s films take their time in the Japanese environment and household. But the film here resonates so deeply because Kore-eda developed the screenplay after his dead father came to him in a dream to visit his soon-to-be dying mother.

He states, “Even though my dead father came to tell me that in a dream — which is not the sort of thing I actually believe in — I still didn’t go home and see my mother. After she was hospitalized, because of my guilt, I spent a lot of time with her.” This quote can be seen to the relationship between the surviving sons, Hiroshi Abe’s Ryota and Yoshio Harada’s Kyohei.

Much of the film deals with the walking-on-eggshells exchanges, glances, and almost real conversations between these two. The relationship is created with purity and honesty by Kore-eda that must have been constantly in his own mind when making the film.

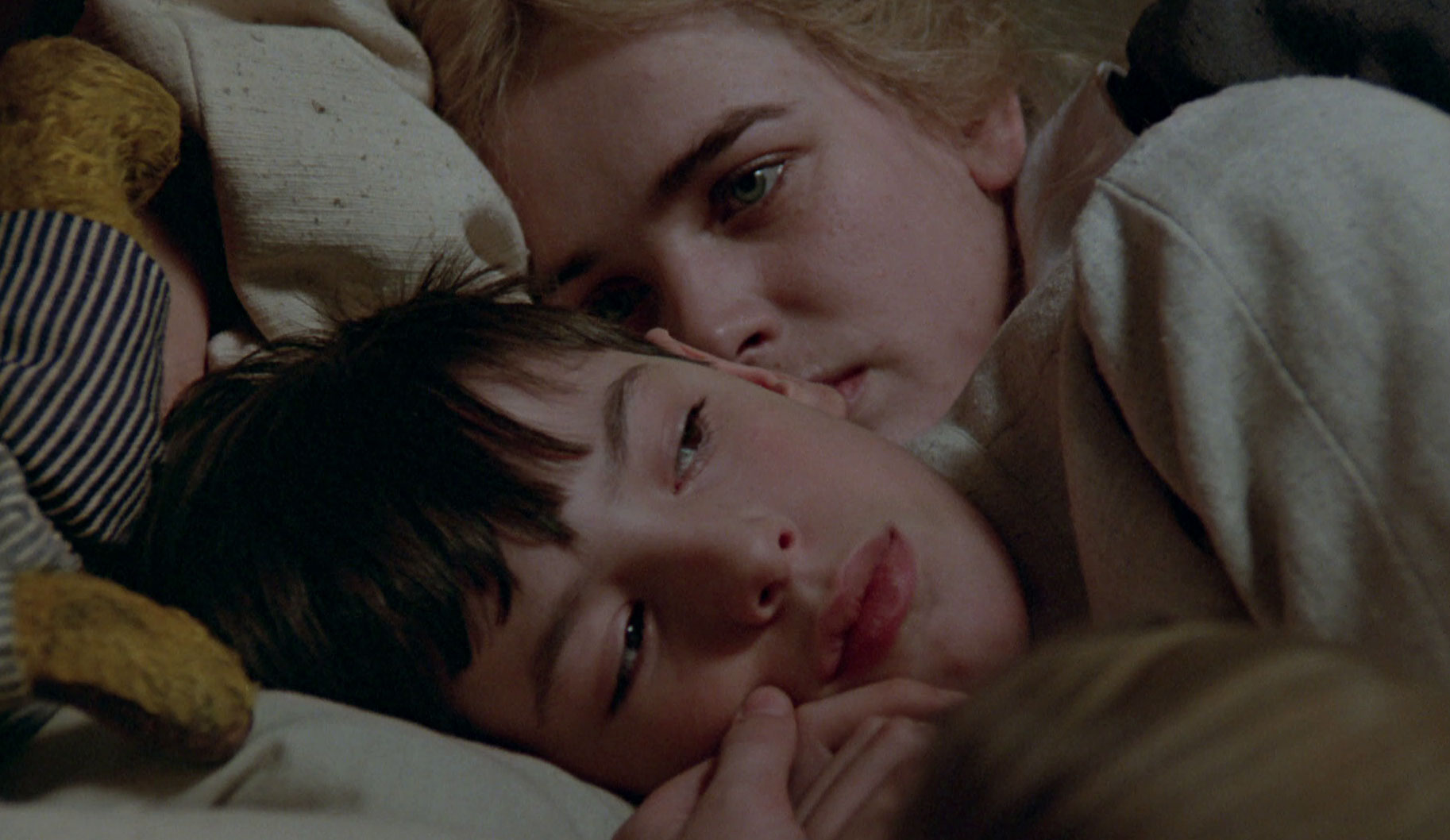

10. Fanny and Alexander (1982) – Ingmar Bergman

The swan song for the legendary director Ingmar Bergman. He combined almost all of his obsessive themes into one film. The dynamics of family, the blending of fantasy and reality, and the strict and brutal effects of religion are in full force in this film.

The film is split into two parts, if you’re watching the theatrical or television version. We see the happy Christmas and holiday spirit of the Ekdahl household in the first part, to the more sinister ruling under Bishop Edvard Vergerus.

Bergman and regular cinematographer Sven Nykvist show the bright, decorative colors in the first part, to the dark, grey, and cold colors in the second part. This could almost be described as Bergman himself. Despite the seriousness of his films, he was a very fun and loving man; on the other side of him, a haunted, cold individual. Therefore, a conflicted artist and complicated man.

He was able to explore of his filmic desires and obsessions in this split narrative. We then see the innocence of Fanny and Alexander seeing the statues move in their house, to playing games while attempting to escape in a cupboard from their new demonic, religious upbringing.

Bergman has stated that many of the members of the Ekdahl family are based on his own family. However, Bergman uses the magic of his images and storytelling to tell a lasting imprint of the viewer’s mind.