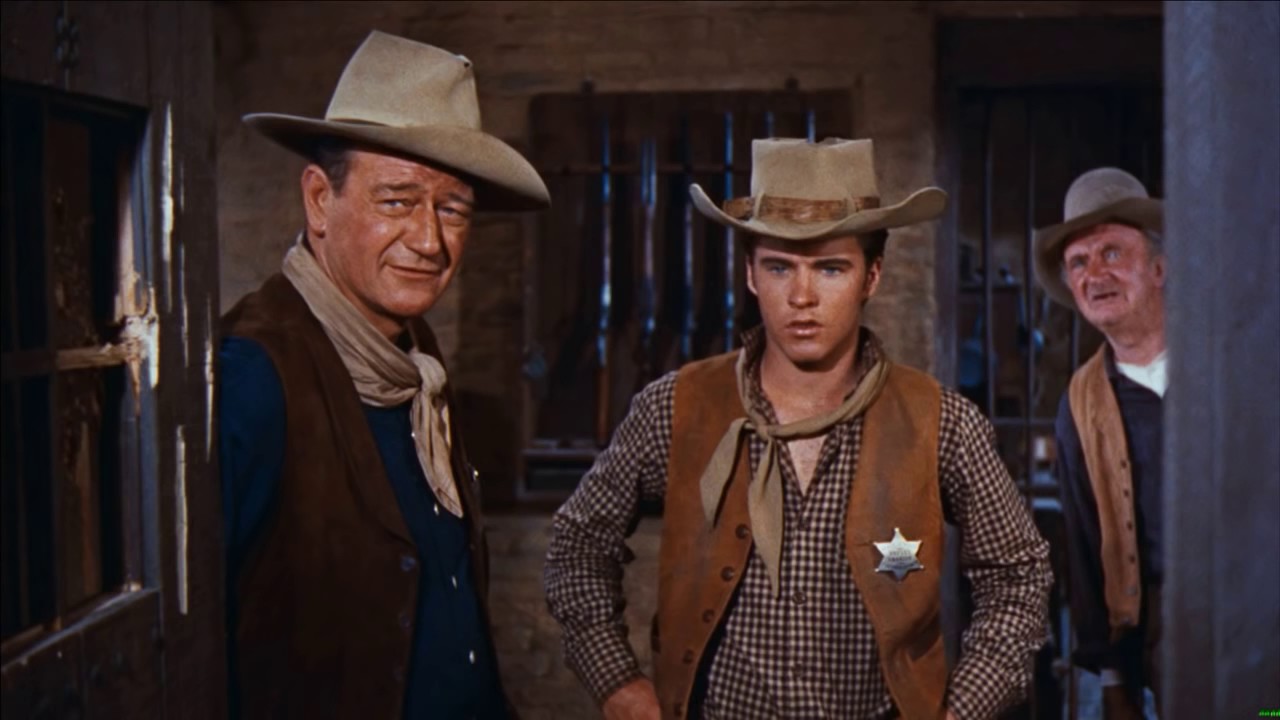

5. Rio Bravo (Howard Hawks, 1959)

Legendary American filmmaker Howard Hawks is a master of entertainment. He directed 1946’s The Big Sleep, one of the coolest films ever made, and other classics such as Scarface, His Girl Friday and Red River. His biggest achievement, however, is one of the all-time great westerns: Rio Bravo.

Not only is it one of the great westerns, but it’s also one of the great films about friendship. Aspiring filmmakers can learn so much from it; building character relationships, characterisation and above all, how to fully embrace the possibilities for entertainment which cinema can offer.

Sheriff John T. Chance (John Wayne) is in charge of keeping order in the small town of Rio Bravo, with the help of his self-conflicted alcoholic deputy Dude (Dean Martin) and permanent fixture of the jailhouse Stumpy (Walter Brennan).

After they arrest local bad guy Joe Burdette for murder, his powerful rancher brother rounds up many men to ensure his sibling goes free. The trio must work together to preserve the law of the land, and unexpectedly enlist the help of young, intelligent hotshot Colorado (Ricky Nelson) to aid them in saving the day.

The emotional heart of the film rests with Dude. Martin turns in a great performance, adding depth to a character we can instantly sympathise with. He is wrestling with addiction as it threatens to completely consume the potential he has exhibited in his past.

Yet – as previously mentioned – this is a tale of friendship, and at the centre of the story is Chance encouraging his friend to be the very best he can be and to overcome his demons, which makes for some heartwarming and tender moments. He gradually overcomes obstacles and proves himself as a methodical lawman with a crack-shot, and this is because of his peers’ expressed belief that he can improve.

It’s also a film about ageing and generational gaps. All four men working together are of different ages; the cool confidence of youth parallels the recklessness of old age, and Chance is the figure of wisdom for Dude to look up to and hopefully become if he follows example.

Components of their unit may be dysfunctional, but together they are strong, allowing each of their personalities to disarm the oncoming threat of men who would gladly see them killed for a fifty-dollar gold piece. These themes are wrapped up in a narrative which has it all: romance, suspense, action, humour. It’s a pleasure to watch again and again.

Rio Bravo is a patient film which allows its characters to blossom and learn, and yet it never feels like there’s a down moment. There is always something to capture our attention, in part due to its magnificent script, offering so much quotable dialogue. In recent years there has been a slight influx in westerns, and those who wish to contribute would find it in their favour to return to Hawks’ film, because it really is the perfect western.

4. The Phantom Carriage (Victor Sjostrom, 1921)

It is essential for aspiring filmmakers to acknowledge how cinema began to later progress, and to understand its origins. A crucial part of this is exposing yourself to a range of silent cinema, and there are many examples which could have made this list: Fritz Lang’s Metropolis, D.W Griffith’s The Birth of a Nation, F.W. Murnau’s Sunrise, to name a few. Instead, the chosen film is Victor Sjostrom’s stunning Swedish film The Phantom Carriage, a significant cinematic moment and early precursor for the Horror genre.

On New Year’s Eve, three drunk friends are gathered in a graveyard discussing the superstition that the last man to die at the end of every year is condemned to drive Death’s carriage and collect the souls of those who die in the new year. One of the men is in fact given the definitive opportunity to explore the truth of this rumour, and finds himself reflecting on the selfish life he has led in the wake of his sudden death.

Sjostrom was a pioneer, and his 1921 film is still highly regarded for its evolutionary achievement in the realm of special effects, sleek incorporation of flashbacks within the narrative structure, and perhaps most discussed, its strong influence on the career of Ingmar Bergman. He even regarded it as the “film of all films”, and claimed to have watched it at least once every single summer.

If Bergman can learn from it, then it’s an imperative lesson to subject oneself to. The influence this film has had on modern cinema is undeniable; another example comes from Stanley Kubrick’s The Shining, as the “Here’s Johnny” scene is a homage to a similar scene here. They are also spiritually comparable in terms of mood and themes.

The Phantom Carriage remains a haunting and moral picture, and it’s a great film to watch when studying techniques and looking for inspiration. For anyone with more than a passing interest in cinema, this is an imperative journey to take.

3. The Mirror (Andrei Tarkovsky, 1975)

Often cited as the greatest filmmaker of all time, Andrei Tarkovsky’s body of work is consistently brilliant and has inspired many. His influence on filmmakers such as Terrence Malick, Lars Von Trier, Michael Haneke and Carlos Reygadas is clear; indeed, many others have paid homage to his most notable works.

While filmmakers have attempted to recapture the mood and imagery of 1975’s Mirror, it is a film which is impossible to imitate. It is a piece so personal and yet so historically political. It begins with a seance to eradicate a stutter – this process of hypnosis allows for clear speech, and that which follows is Tarkovsky’s cinematically pure voice. Thematically it deals with time, memory, repetition, inheritance, with the object of a mirror symbolising reflection, and perhaps the proposition of existing in a moment of time more than once.

The film is poetry, conveyed both visually and verbally. It spellbindingly comments on the way in which we can return to places and moments from our past, transported by conscious dreams. Exploring such a concept allows for some complex and unforgettable imagery, but also some of the most beautifully frightening; soaking wet and impossibly-dark hair disguising the human form spliced with crumbling and collapsing interiors appear particularly unsettling.

The visuals that Tarkovsky rewards life are made even more impressive courtesy of magisterial and lucid camerawork, giving the impression of nature operating as spectator to reveal an immaculate existence, not just in the depiction of childhood, but even in sadness.

Nature acts as a guiding force, exemplified early in the narrative by the presence of strong winds as signal. Despite the character’s prior acknowledgement of nature’s role, he ignores it. It’s an incredibly powerful moment.

It is a film so personal, and despite this, it has touched so many and provided audiences the opportunity to discover their own interpretation and meaning. Everyone can project their own feelings towards family and their history onto it, and yet, we cannot experience it without learning about Andrei Tarkovsky himself, and also Russian history, as he flits between prewar, war and postwar timeframes.

To enjoy and learn from Mirror you must cooperate with it and expose yourself to the feelings and moods it expresses. It would be a deep shame for any filmmaker – existing or aspiring – to miss out on witnessing the works of the great master.

2. Mandy (Panos Cosmatos, 2018)

Try not to immediately dismiss this entry, it deserves to be included. There are so many classic films that should be considered imperative viewing for existing and aspiring filmmakers that it would be easy to ignore current achievements.

However, it is important that we recognise and appreciate what is being made right now; what limits are being pushed? How are recent filmmakers choosing to innovate the medium? Panos Cosmatos is a filmmaker making a great impression, and his film Mandy is possibly the best film to release this year.

Red (Nicolas Cage) and Mandy (Andrea Riseborough) are a couple living an idyllic life out in the secluded forest by Crystal Lake. Sadly, their union is forced into separation when the members of an unhinged cult spy her wandering down the road.

The leader – Jeremiah Sand (Linus Roache) – decides that he must have her. The group use a mystical horn to summon a gang of Black Skulls: nightmarish bikers who have been horrifically transformed by a powerful batch of LSD. After Mandy is brutally taken away, Red must hunt down those responsible for the loss of his love and exact his grisly revenge.

The film is unlike anything else in recent memory. Cosmatos crafted his directorial feature debut back in 2010, Beyond the Black Rainbow, which was a dull and too obviously inspired slice of deranged sci-fi. It failed to reach many, yet his second effort has garnered significant attention. Mandy has become somewhat of a midnight-movie sensation, selling out theaters and receiving praise from critics and audiences alike.

It is a film of two halves which breathtakingly combine. For the viewer to invest in the direction the film takes, they must believe in the beautiful bond between Red and Mandy, which we wholeheartedly do thanks to Cage’s and Riseborough’s magnetic chemistry.

Johann Johannsson’s score compliments an otherworldly and distinct visual style, helping Cosmatos bring us a universe we have never visited before. The surreal landscapes gradually become more extreme, eventually spitting us out and making us question where we are and the road we have travelled to get here. It really is a mesmerising experience.

Mandy certainly won’t be to everyone’s tastes, but those who enjoy the work of Alejandro Jodorowsky, 1981’s Heavy Metal and Clive Barker’s Hellraiser will find something to cherish here. Filmmakers should watch this and see how high the modern boundary is being set for following through on artistic vision.

It’s a warning never to compromise, but instead to believe and follow your instincts. This is clearly the product of a man hypnotised; who has delved deep into his profession with jaw-dropping results. Take note.

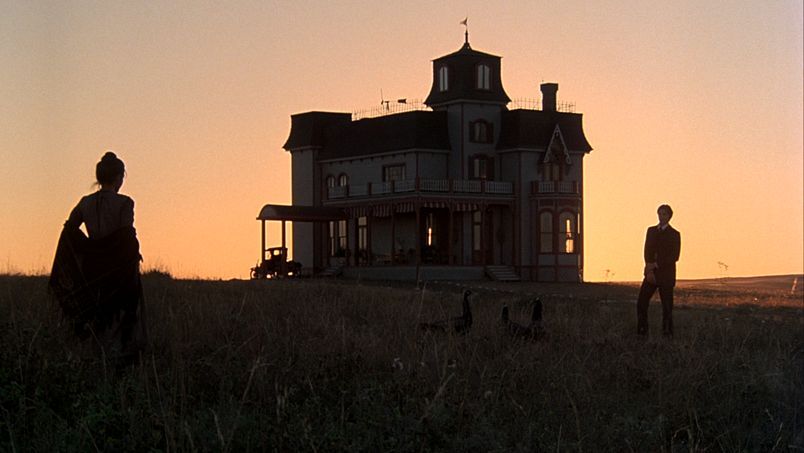

1. Days of Heaven (Terrence Malick, 1978)

We have finally arrived at Terrence Malick’s 1978 masterpiece Days of Heaven, quite possibly a perfect film. It won the Academy Award for Best Cinematography, and bagged Malick the Best Director honour at the Cannes Film Festival.

The Illinois-born maverick’s second feature is an unforgettable feat of filmmaking, and is destined to be appreciated more and more as it continues to age. It is testament to the director’s devotion and patience for overcoming obstacles, only accepting satisfaction when the results looked as good as humanly possible.

The film tells the story of a love triangle between two men (played by Richard Gere and Sam Shepard) and the charming Abby (Brooke Adams). Bill (Gere) is a labourer working on the farm of a rich Texan (Shepard) with his love Abby, who is posing as his sister.

Hearing that their boss may not have long left to live, Bill convinces Abby to romance him and claim his fortune. Complications arise when her compassion is divided by the happiness she finds in both of their company; she is left conflicted, and as the two men become increasingly suspicious of the nature of the arrangement, Abby must confront a final decision.

There is so much to observe when watching this film, and there really is no number of viewings which can lessen its beauty. It was shot almost entirely at “magic hour”, and was the first film to take advantage of a new Eastman ultra light-sensitive stock negative which facilitated Malick’s instructions to shoot only at the most gorgeous and cinematic times of day.

After some time, he even disregarded the script and encouraged the actors to “find the story” – this honourable approach lasted for almost a year of its rather lengthy production, two years of which were committed to the editing process. The sheer commitment of the cast and crew is so heartening, and all of their strenuous work paid off.

It’s hard to believe that the film’s cinematographer was going blind during filming – Nestor Almendros – because what he helped create is one of the most beautiful films in all of cinema. His work here is often the most praised aspect, yet less often given the shining credit it truly deserves is Linda Manz’s astonishing performance. Her narration and closing monologue provides the picture a haunting soul.

It’s a masterclass in sound, cinematography, editing; everything really. Days of Heaven is a miracle, and those who wish to appreciate the magic of cinema should look no further. Malick’s masterpiece will continue to inspire filmmakers new and old, always.