17. PI (1998, Darren Aronofsky)

Pi is a portrait of madness, of crumbling certainties and the slow disintegration of a human mind. It is the story a man attempting to find mathematical structure in an otherwise chaotic universe, tapping into our eternal fears of death, the afterlife and the omnipresence of God.

Aronofsky is known for his dark dreams of addiction and obsession; Requiem for a Dream is one of the most harrowing films of all time, and he bucked the trend for Oscar nominations with his dark, Argento-inspired Black Swan. But Pi is something else, a low-budget thrill-ride that shoots for a sheer cerebral experience of paranoia, terror and insanity. It was made on a shoestring, but looks absolutely fantastic, with clear black and white cinematography, suffocating camera angles and bursts of synaptic violence.

16. The Lobster (2015, Yorgos Lanthimos)

The Lobster is the latest movie on this list, and also made by Greek director Yorgos Lanthimos (see: Dogtooth, above). Its premise is at once strange and astounding: people living in a near-future society have only 45 days to find true love or they are transformed into an animal of their choice, and made to wander, alone, forever.

In a way, it is a satire of human relationships; the characters are weirdly emotionless, robotic even, knowing that romance is statutory rather than passionate, putting themselves through the rituals of courtship in order to fulfil legal requirements.

It mimics the ceremonies of loneliness, of those in society who have nobody to cling to, or who find human relationships difficult. Lanthimos is one of the most innovative directors working in cinema today; his films glimpse everyday realities in ways that are both new and surprising.

15. WR: Mysteries of the Organism (1971, Dušan Makavejev)

Communism, and the deterioration of the Eastern bloc throughout the latter half of the 20th century, was a source of material ripe for filmmakers, many of whom were indicted or persecuted for their art. And none is so remarkable or original as Makavejev’s Mysteries of the Organism, a blending of socialism, sex and comedy that works as a kind of anti-documentary against the state.

It came under direct criticism in the west as well as the east upon release, with many declaring that it was a ‘crime against film’, or an aesthetic backwater. It is, indeed, a startlingly unique piece of cinema, made in a nation where politics was crumbling apart and terrible violence was on the immediate horizon.

The film concerns a quest for a perfect orgasm, and cleverly depicts and ridicules authority figures in the vulnerability of sexual activity. It is initially the story of a Freudian scholar, who declares that the quest for sexual pleasure is the ‘only source of happiness’, and then commences to illustrate this notion in truly surreal fashion, with ‘shopping channel’ style vignettes, sex education classes that go hilariously awry, and wanton violence of all kinds.

14. Taxidermia (2006, György Pálfi)

Pálfi has directed two of the most unique and unsettling films of the last decade or so: the almost completely silent Hukkle (2002), and Taxidermia, a blend of gross-out body horror, arthouse sensibilities and epic literary storytelling. The film echoes the writings of Gunter Grass, Gabriel Garcia Marquez and Salman Rushdie in its overtly magical narrative, but adds a little Cannibal Holocaust along the way.

Pálfi is seemingly obsessed with bodily functions and excreta of all kinds, as well as the extreme limits to which the human body can be pushed, and he forces three generations of characters to undergo strange bodily modifications, culminating in the self-decapitation of a taxidermist, who seeks to display his own preserved carcass as an exhibit.

Is it an allegory for the Hungarian nation during Communist occupation? Or a comment on the forms of political dismemberments that occur in authoritarian states? Whatever Pálfi’s intentions, Taxidermia is unique and strange, and certainly worth a place on this list.

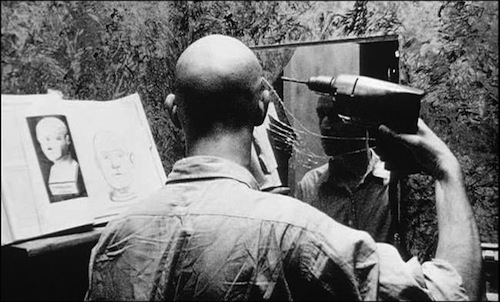

13. Videodrome (1983, David Cronenberg)

Beginning with Shivers in 1975, Cronenberg had become the preeminent North American embodiment of pure horror. His run of films in the late 1970s and 1980s are some of the finest, most audacious horror movies ever made. Videodrome is one of the movies that appears on many ‘weird’ lists, but its most famous sequences are deserving of praise.

The basic premise of Cronenberg’s classic Videodrome is worryingly plausible in the internet age: a man stumbles upon a television channel that apparently broadcasts real-life human torture and sadism, and becomes increasingly caught up in a web of strange hallucinations and paranoid conspiracies attempting to discover its signal.

In the age of Video Nasties and the ‘snuff film’, when the new-fangled availability of home video spawned all manner of urban myths and legends, (Charlie Sheen once took a copy of notorious Japanese splatter-horror Flowers of Flesh and Blood to police in the belief that it depicted a real murder), Videodrome preyed upon fears that were very real, and did it with Cronenberg’s trademark strangeness.

12. On The Silver Globe (1988, Andrzej Żuławski)

One of the greatest acts of pure imagining in cinematic history, on par with Jodorowsky’s Dune, On the Silver Globe is mostly overlooked in lists of the greatest science fiction films, or any lists for that matter. Like other films on this list, it was subject to the scissors of censorship, being filmed in communist Poland; it is, tragically, still incomplete.

Despite this, it is a remarkable creation, a moral warning, a kind of message from a possible future, and incredibly audacious in scope and creation. It is also immensely and singularly distinctive, an exploding star of a movie that channels nihilistic philosophies into a (mostly) cohesive narrative.

The story itself is a kind of Biblical allegory, and concerns humanity’s attempts to settle another planet, and the cosmological and humanistic epiphanies that come from leaving our terrestrial home.

‘Moon-children’ of astronauts who visit the moon form an increasingly paganistic society that survives for many generations, idolising and worshipping original humans who arrive as prophetic visitations. When an astronaut appears and fails to help the Children win a war against the brutal Szerns, telepathic half-bird men who enslave the ‘Moon-children’, he is crucified for his failure to fulfil the prophecy.

If this sounds strange, and somewhat incomprehensible, it is. But On the Silver Globe is also the greatest science fiction movie you have never seen.

11. Enter The Void (2009, Gasper Noe)

Gasper Noe’s Irreversible is one of the most controversial films ever made, beginning with the bludgeoning to death of a man with a fire extinguisher and containing an extended ten-minute rape-scene that is essentially unwatchable. It is an extreme movie, one designed to shock and disgust. Eight years later, Noe made Enter the Void, a kind of pseudo-spiritual sequel to Irreversible, that offers psychological shudders to the purely physical shocks of its predecessor.

Enter the Void portrays a man’s voyage following violent death in a neon-soaked, pornographic Tokyo of the future. His death is not a religious experience; more an ascension to another plane, a la Space Odyssey, where he can observe the brutality and sorrow of his life, and its aftermath, without the constraints of space-time.

The film is an ambient sound-scape, full of epileptic camerawork and filmed predominantly through the eyes of the dead man, who descends through Hellish visions of an underworld that all-too-readily resembles our own. Noe is not a director for the faint of heart; his films are likely to invoke convulsions, or deep bouts of melancholy.

Yet Enter the Void has a beating heart that Irreversible, purely reptilian and distant, did not. It is a film that pushes the boundaries of cinematography and experiments with the effects of imagery on the mind and the subconscious.

10. Gummo (1997, Harmony Korine)

What to say about Gummo? It is a film that could only be made in the 1990s, when independent American cinema burst into flower, and directors such as Todd Solondz, Gus van Sandt, Kevin Smith, Wes Anderson and Spike Jonze could emerge from beneath the hard blanket of the Hollywood system. Harmony Korine, however, is the ultimate personification of 1990s American independent cinema and its ability to spawn new and unthinkable visions, and Gummo is his magum opus of anti-social, repulsive intentions.

Gummo is the story of a group of dead-beats who live in a town destroyed by a tornado. With society already crushed and broken, they pass the time by huffing household cleaning products, killing cats, avoiding molestation and engaging in generally unpleasant behaviour.

The film, like many on the list, is more a series of fragments and occurrences, existing under the canopy of an overarching theme of moral and ethical decay; many of the town’s inhabitants are involved in behaviours that would be entirely unacceptable in normal society. Korine revels in the putridness and self-awareness of it all, following these characters as others would great historical figures.

9. Conspirators of Pleasure (1996, Jan Švankmajer)

Even in a list of weird movies, Conspirators of Pleasure stands out. Svankmajer had previously made a series of sadomasochistic stop-motion animations, and this was his first ‘live-action’ film (though there are scenes involving puppetry). Several characters implicate themselves in a set of ‘conspiracies’ to engage in mutual sexual fantasies involving elaborate costumes, bodily harm and animals.

Fetishism is not new to cinema. Bunuel has depicted it on a grand scale since the 1930s, and Cronenberg detailed the erotic and the horrific in 1996’s Crash. Horror also takes its inspiration from the world of fetishism, most notably the Hellraiser series. Yet, here we have a strangely personal vision of fetishism. The film essentially concerns the strange and intimately private rituals of preparation people enact to fulfil their private, deepest obsessions and desires.

It is a film about sexual objects that are not themselves overtly sexual. These are dreams and cravings that never see the light of day, and Svankmajer revels in the absurdity and liberation of portraying purely visual fetishes (the film is wordless) with oblique romanticism, obviously recognizing the emancipation involved in the fulfilment of sexual desire, however odd or abnormal.