6. Not One Less (1999)

Despite some controversy from the Cannes Film Festival, which eventually led Zhang to withdraw both of his films from the program, “Not One Less” became another international success, netting four awards from the Venice Film Festival (including the Golden Lion).

The story is adapted from Shi Xiangsheng’s 1997 story “A Sun in the Sky” and revolves around 13-year-old Wei Minzhi, who arrives in Shiquan village to substitute for the only teacher there, Gao, who is about to take a month’s leave to take care of his ill mother.

As the phenomenon of children leaving school to go to work in factories has become a major issue for the village, Gao promises Wei to give her 10 yuan if no student has abandoned school by his return. When one of the students leaves, Wei tries to bring her back, and is willing to go to extremes to accomplish that.

Zhang directs a tender and very moving film that focuses on presenting the faults of the Chinese educational system and the benefits of patience and persistence. This time, his visual style is more realistic, focusing on the frugal and simplistic environment. The dialogues are austere, as his protagonists are children without previous acting experience, but through these tactics, he manages to perfectly captivate the reality of the circumstances in the country, as he highlights the fact that the individual is almost ignored in front of the common good.

5. Hero (2002)

During the Warring States Period, China was divided into seven kingdoms. Among them, the most powerful was Qin, whose king’s purpose was to conquer the other six and become emperor. Because of this fact, a number of assassins threatened his life, chiefly among them Broken Sword and his loved one Flying Snow, and Long Sky with his assistant Moon.

Qin promised glory and honor to whoever managed to kill the aforementioned. Eventually, in front of him appears another assassin known as Nameless, who alleges that he had killed all of them and presents their weapons as proof. Subsequently, the king asks him to tell the story.

Through a number of flashbacks, Nameless explains what happened. But is he actually the one who killed the other assassins, or is his presence just an excuse to kill the king?

Inspired largely from “Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon”, “Hero” is another technically sublime film, with solid cinematography and costumes, and an overall incredible production value.

Furthermore, Zhang drew heavily from the chemistry between Tony Leung and Maggie Cheung to present a film with equal parts action and drama.

In that fashion, the action scenes may be far less violent than they usually are in this genre, but they compensate by being elaborate and artistically competent.

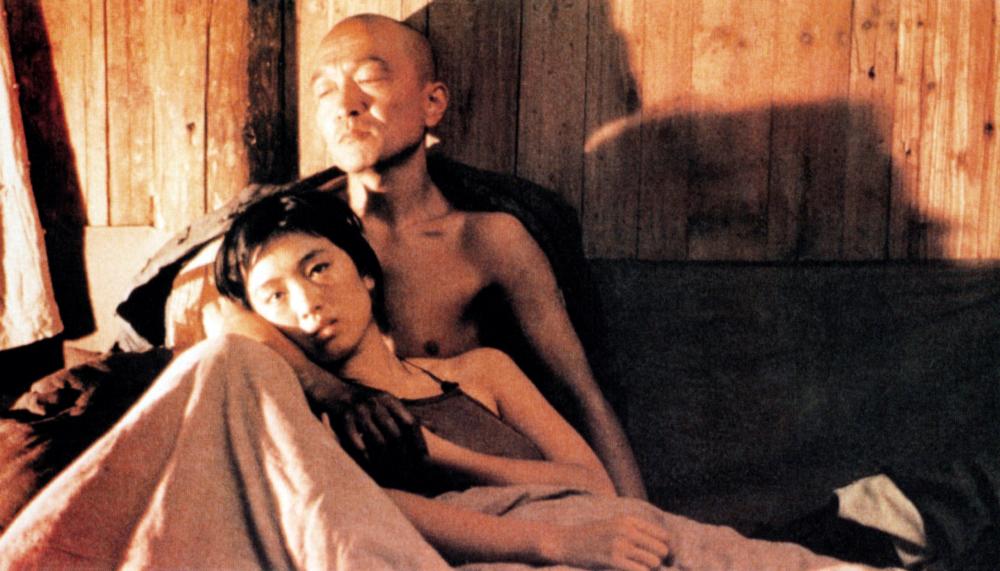

4. Ju Dou (1990)

Zhang’s second (third if you count “Codename Cougar”) feature was a very significant film for the local industry, since it was the first Chinese film to be nominated for an Academy Award for Best Foreign Language Film in 1990.

Ju Dou is a beautiful country girl who is purchased by Yang Jinshan, the elderly owner of a fabric-dyeing corporation,. The man had already beaten his previous two wives to death, and the harsh treatment continues with his new wife. However, when his adopted nephew, who also works for him, meets Ju Dou, he falls immediately in love with her, and the feeling is reciprocated. Furthermore, the two of them eventually have a child together and the old man suffers a stroke that leaves him paralyzed from the waist down.

The two lovers take over the business as they stop hiding their love for each other. Their happiness, however, does not last long.

Zhang Zhang directs a movie about forbidden love, stressing the fact that the sentiment cannot be bound by any rules, even if the opposite results to social outcry and tragedy. His narrative is laconic and dark, as he implements a rather realistic presentation of his characters, in natural size.

The action is restricted in a sole environment, the fabric-dyeing mill, where the wooden handheld machinery and the huge balls of cloth dominate the space. The red color dominates the images and is the main ingredient of the visual prowess that permeates the film.

3. The Story of Qiu Ju (1992)

Based on Chen Yunabin’s novella “The Wan Family’s Lawsuit”, the film was a huge success in the festival circuit, earning a plethora of awards, including the Golden Lion for Zhang and the Golden Ciak for Gong Li, from the Venice Film Festival.

The leader of the village kicks Qinglai during a heated discussion, and his beating is so harsh that he has to abstain from work for some days. Qiu Ju, his pregnant wife, complains to the local police officer and he makes the village chief pay 200 yuan to Qinglai.

When Qiu Ju goes to the headman, he insultingly throws the 200 yuan notes onto the ground and refuses to apologize. Qiu Zu refuses to pick up the money and embarks on a journey that will bring her to the highest grades of Chinese justice in order to exact a proper apology. Bureaucracy, however, proves a monster not easily dealt with.

Zhang presents a realistic (to the point of documentary image) of contemporary China, particularly regarding the faults of the system. The sense of authority shown by figures as small as the village chief is one of them, and the blights of the bureaucracy the other. However, the film shows that the system works on some level, but it takes intense persistence to accomplish anything and even when someone does, the result may be completely different than what was expected.

Regarding that last aspect, Zhang even manages to inject the film with a sense of humor, which puts a nice stroke of entertainment value in a rather pessimistic film.

Gong Li is astonishing in the titular role, presenting a woman determined to achieve her goals with nothing but sheer courage.

2. To Live (1994)

The film is based on the homonymous novel by Yu Hua, and spawned much controversy in China due to its critique of the Communist government, to the point that it was banned in mainland China. However, it managed to win a plethora of international awards, including three from the Cannes Film Festival.

The story revolves around a spoiled rich man’s son named Xu Fugui, who is also a compulsive gambler, and his wife, Jiazhen, who has to struggle with his behaviour. However, when he loses his family’s property while gambling, she decides to leave him, along with their daughter.

Soon after, the Chinese Civil War breaks out and the family is caught between the two armies, having to perform shadow puppets for the soldiers. The story then forwards to the time of the Great Leap Forward, with the struggles of the family continuing in a new setting.

Zhang directs a film that shows the insignificance of man in the whirlwind of China’s history, and in that fashion, presents his take on these events through the lives of the family members. His critique on the regime is rather pointy, starting with the violent uprooting of the middle and upper classes of the previous political situation, and ending with the amateur practices of its members that conclude the film.

Gong Li is astonishing as Jiazhen, but the one who steals the show is Ge You as Xu Fugui, as he portrays elaborately a man who manages to transform in order to survive, who, despite the innumerable blights of his life, manages to live.

1. Raise the Red Lantern (1991)

Zhang’s magnum opus is his most acclaimed work, netting awards from most of the major festivals around the world, and an Academy Award nomination for Best Foreign Language Film. The script is based on Su Tong’s novel “Wives and Concubines”.

The story revolves around Songlian, who, after her father’s death, becomes the fourth wife of Lord Chen and moves into his mansion. Initially, everything seem to be going well for her, as she enjoys the greatest honors among the four wives. However, as time passes, the first clashes start to appear, and Songlian eventually realizes that the mansion is a place of treachery and politics, through the constant antagonism among the four women.

The film’s title refers to one of the key elements of the story, as, each day, Lord Chen announces the wife with whom he will spent the night, and the servants raise and light the red lanterns at her apartments.

Zhang’s collaborations with Gong Li found their apogee in this film, with Li portraying Songlian in astonishing fashion. The highlight of her performance is her transformation from a naive girl to a disillusioned woman, destroyed from the understanding of her fate and the fate of one of the other women in the house.

The movie features masterful cinematography with the cooperation of Lun Yang and Yiping Zhao.The cinematography is actually a part of the story, mainly through the master shot of the central courtyard of the house, which is open to the sky, and features of the wives’ apartments on both sides and the master’s in the end.

The passing of each season is witnessed through the state of this courtyard as it becomes filled with snow or wet from rain or bathed in sun. Furthermore, the interior of the house is ominously shot, in a clear parallel with Songlian’s plight. Zhang used very bright colors through the Technicolor medium, with its usual richness of red being particularly evident in the titular lanterns.

Author Bio: Panos Kotzathanasis is a film critic who focuses on the cinema of East Asia. He enjoys films from all genres, although he is a big fan of exploitation. You can follow him on Facebook or Twitter.