8. Ilo Ilo (2013) dir. Anthony Chen

Ilo Ilo was the debut feature-length film of Singaporean director Anthony Chen. It was awarded Camera d’Or after its premiere in Cannes during the Directors’ Fortnight. In spite of its international cast, it was produced entirely in Singapore and is therefore not included under Pan-Asian umbrella.

The safest way to approach this film is to decipher the secret (at least to a Western ear) formula that is concealed in the film’s title. The cryptic Ilo Ilo stands for nothing more than “Mom and Dad Are Not Home.” And while the parents are too busy being grown-ups, their young son Jiale grows closer to the family’s new housemaid, Teresa, who opens the young boy’s eyes to the lives and suffering of people around him. Far from being overtly didactic, Ilo Ilo is a little cinematic Bildungsroman that is heart-warming and humane from first to last.

9. Norte, the End of History (2013) dir. Lav Diaz

By far the longest film on this list, Norte, the End of History is 250 minutes long. In these four hours the director Lav Diaz packs a very elaborate (as well as searing!) account of a crime that completely changes the lives of three people: an innocent couple, Joaquin and Eliza, who are charged with murder and are unable to alter the sentence, and the real murderer Fabian who under the influence of the crime he had committed begins to reflect on the history of the Philippines and the almost tangible sense of misery that seems have been following his motherland since its very foundation.

But don’t let the running time discourage you: four hours may seem like an eternity, but when Lav Diaz is the helmsman, you would soon stop noting the passage of time, or rather the time itself would become more fluid and malleable.

Probably by the end of the movie you would know as much about the tumultuous history of the Philippines as you would have learned after a whole month traveling around the country. And if that’s still not enough, an overwhelmingly positive reception that the film enjoyed should be the most convincing reason for giving this slow cinema epic a watch.

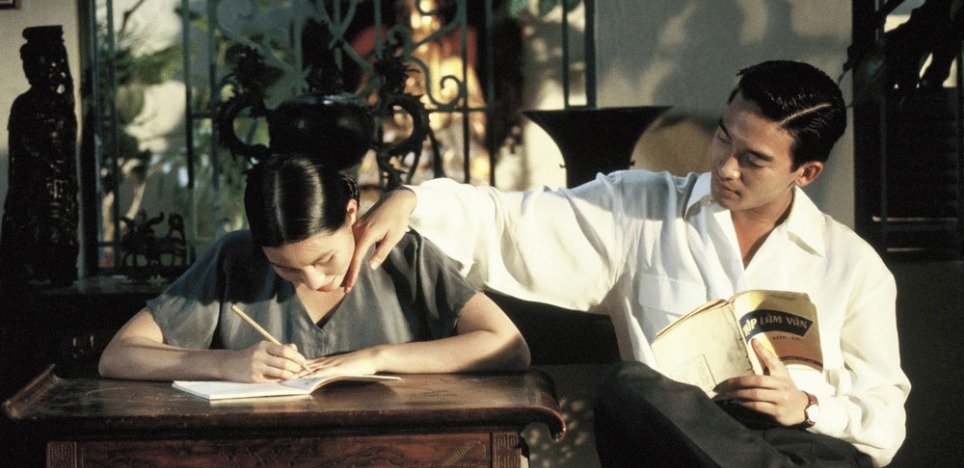

10. The Scent of Green Papaya (1993) dir. Tran Ahn Hung

The Scent of Green Papaya is an all-time classic of Asian cinematography directed and written by Tran Ahn Hung. The long list of awards that the film won include Camera d’Or from Cannes, Cesar Award for Debut film and even an Oscar nomination. The film enjoys a rating of 4/4 from Roger Ebert and is given a 100% “fresh” score on Rotten Tomatoes.

Apart from being stunning visually, the film boasts a fairly novel plot line, in which a young servant girl, Mui, refuses to submit to the vicissitudes of her unhappy life and, after a series of rather unfortunate events, becomes an inspiration for a composer who, having fallen in love with her, finds enough determination to undertake the education of his wife-to-be.

For an Asian viewer, the drama may seem even more acute, as the film touches on a number of rather sensitive topics — such as disintegrating social stratification, infidelity, and unequal marriage — which, while being tolerated, are not publicly acknowledged or discussed in many eastern societies.

11. The Woman in the Septic Tank (2011) dir. Marlon N. Rivera

If some of the films on this list seemed to tempt especially impressionable viewers into the too-well-explored realms of critical interpretation, The Woman in the Septic Tank is an artistic statement that calls for no interpretation — if only because something unpleasant may surface in the process.

The film is a brazen satire on nothing less than the independent film industry, with the three protagonists setting out to shoot a film that would be an immediate international success. There’s only one thing they seemed to have forgotten about: that filmmakers should actually take interest in the subject they are exploring. But this so-called ‘interest’ never occurred to them to be of the slightest importance whatsoever.

What follows in a funny but not-too-reverent account of film production and various ploys the aspiring filmmakers are willing to engage in to bring their project to fruition. The real question that inevitably springs to mind of every attentive viewer after watching the film is how many movies are actually nothing more than well-hidden and heavily sugared hypocrisies.

12. The Big Durian (2003) dir. Amir Muhammad

Durian is a fruit native to Southeast Asia: the pulp of durian is a bit like custard, very sweet and very mushy. But there’s one thing that makes the first encounter with durians a truly unforgettable experience: durians are universally known as the world’s stinkiest fruits. How are durians related to the solitary soldier who opened fire on civilians in one of the neighborhoods of Kuala Lumpur? — that’s for the viewer to decide.

The director Amir Muhammad’s take on this inexplicable attack unearths a number of rather unpleasant racial prejudices which the capital was rife with during the attack. With a cast of amateur actors and civilians, The Big Durian offers a glimpse into a racially-charged society that is at once apathetic and highly biased. But while in peacetime the feelings are artfully concealed, at the time of an open confrontation they elevate quickly and wound more people than the original attacker could ever hope for.

13. Motel Mist (2016) dir. Prabda Yoon

One of the newest film on this list, Motel Mist is the latest work of Prabda Yood, a Thai director who is considered among the country’s most innovative filmmakers. Motel Mist is a story of what happens behind the always closed doors of a public house, but, far from being a simple Southeast Asian social drama, the film combines a number of surreal elements and rather sophisticated visual solutions that would leave no one impartial.

In one of the interviews, Prabda confessed that he had always wanted to write a story about the secrets that inhabit public houses, which over the years have become a familiar presence on the streets of Thai cities. Yet, despite the proliferation of such establishments, their existence is never fully recognized — let alone discussed — by the general public.

Thus, the motel in Motel Mist acquires a more symbolic meaning as a dirty secret that the public is unwilling to wake up to. The tension created by the recent political unrest in the country heavily contributed to this interpretation, which explains why some Thai critics saw anti-state messages in Yoon’s cryptic feature.

14. Sandcastle (2010) dir. Boo Junfeng

In 2010, Sandcastle, written and directed by the young Singaporean director Boo Junfeng premiered at the Cannes Film Festival, thus becoming the first Singaporean film to be shown at the International Critics’ Week. The story follows a young man, En, who finds himself on the verge of entering military service. Yet even before this important step in his life, En’s family (and all the secrets and memories that it holds) doesn’t release its grip on him. In just a few days, En fills in the blanks in his family’s past, and a series of unexpected discoveries irremediable alters his worldview.

Sandcastle is a touching account of young adolescence, of growing up, and of letting go of youthful idealism, which Junfeng and his crew masterfully caught on film. Sandcastle offers a uniquely vicarious experience of looking at life through the eyes of an 18-year-old — for some viewers, it means re-living the past; for others, snatching a glimpse of the time-to-come.

15. Imburnal (2008) dir. Sherad Anthony Sanchez

The second-longest film on this list, Imburnal is 3 1/2 hour long story of two boys growing up on the outskirts of Davao City in the Philippines. Having spent their childhoods amid dust heaps and violence, the two boys’ later lives unfold in the manner that would make behaviorist gloat with satisfaction. Yet the drama of their lives is not shown explicitly, and there are no Hollywood-like pangs of conscience and flashbacks to especially excruciating experiences of childhood.

The disjointed narrative and long shots seem to invite the scene to arrange itself, as if out of that arrangement the action must necessarily follow. And, rather surprisingly, most of the time it does: sometimes vehemently and lively, sometimes slowly and reluctantly. But, like the feeble flame of a candle, it is ever ready to go out, which it does at about 90-minute mark, and then viewer is invited to enjoy the black screen interrupted only by a sound of running water.

Author Bio: Eugene Tantsurin lives and studies in Bangkok. He reads a lot and write almost as much. He also likes Belle and Sebastian and cute girls in academia.