5. Colourful yet stately and very controlled cinematography

Read any description of Almodóvar’s work, and one of the first elements to be discussed will nearly always be his sense of style. He loves strong, primary blocks of colour and extrovert costume design (Kika, tellingly, has Jean-Paul Gaultier on such duties), and combined with the madcap mood of his earlier comedies, there is the sense of a director always teetering on the edge of complete and utter mayhem.

It is forever threatening to be overblown, overwrought melodrama, with screaming colours alongside screaming actors. So why don’t films like Women on the Verge of a Nervous Breakdown, What Have I Done to Deserve This? and Matador fall into their soap opera abysses?

Simple. For all Almodóvar’s love of style and brightness, his sense of framing and composition within the screen is second to none. There is a control and strength to his imagery, aided by the extremely talented cinematographers he surrounds himself with.

Few directors are as capable as he is at drawing your eye to a detail or an actor’s gesture as he is. One can tell that he aches over the composition of his shots, choosing and selecting them carefully, all to manipulate or generate a specific emotional reaction in the audience.

Returning again to All About My Mother, let’s look at the opening credits. The camera, in an close detail shot, fixes its gaze across a variety of standard hospital equipment.

It tracks their details moving only in straight horizontal or vertical lines, picking out the flashes of colour within them, whilst the credits roll on screen. Finally, it lifts its gaze upwards and frames Cecilia Roth in closeup. It is a stately series of movements.

The interest in the details of hospital equipment prefigures the film’s occupation with illness and death within families. Detail shots like this, that pick out and focus on small objects, are commonplace in Almodóvar’s world, and a fine example of his brilliant visual imagination which brings to life his stories.

Another great example is a shot in Volver, arguably the most famous and most emblematic shot in all Almodóvar’s cinema. Attempting to hide the body of her dead husband, Penélope Cruz is shown cleaning a bloodied knife in the sink.

The shot is a bird’s-eye view from above: the knife being cleaned in the sink and Cruz’s breasts feature heavily. Jean-Luc Godard once said “all you need for a movie is a girl and a gun”. A simpler weapon will do just as well it turns out.

6. The surviving power of women

Pedro Almodóvar loves women. He adores them. They have starring roles in nearly all of his films, and even in those where they’re not front and centre, such as Talk to Her or Live Flesh, they are the still the drivers of the narrative; the engine that pushes the men forward into their own emotional worlds.

Indeed, in a world where a huge number of major mainstream of films don’t pass the Bechtel test, let alone even produce one significant female character, Almodóvar’s world is once again a refreshing respite. Where most films allow men to drive the narrative, and resign women to roles that are defined by the men around them, Almodóvar does the exact opposite.

What is Volver if not a story about women who, having all gone through their own respective tragedies and heartbreaks, bond together to become stronger as a collective. What is Kika if not a darkly comic satire about the media manipulation of women’s struggles, and their reductive narratives, done through the prism of a woman who through the film becomes stronger by not letting herself be reduced to narrative archetypes.

What is What Have I Done to Deserve This? if not a film about the emancipation of a woman at the lowest end of the socio-economic spectrum – a housewife in an overcrowded, ugly apartment with no outlet for her creativity and ignored by those around her – and what is All About My Mother if not a film solely about women and nothing but.

Few male directors have created films which treats women with as much complexity, fluidity and range as Pedro Almodóvar. It even speaks volumes for his ability to do this that he is at his weakest as a director when he is focusing on the world of men.

Talk to Her works because it is a film about men lost within the world of women. Live Flesh however (in this writer’s opinion his worst film), is a drab, dull thriller about two heterosexual men, and Almodóvar fails to make them dramatically interesting as characters in any way whatsoever.

7. Sexual abuse and violence

The themes of sexual abuse and violence crop up frequently in Almodóvar’s work, and it is here where many of his critics have chosen to attack him on the basis of a perceived misogyny in the director’s works. On a surface level, it is possible to see why.

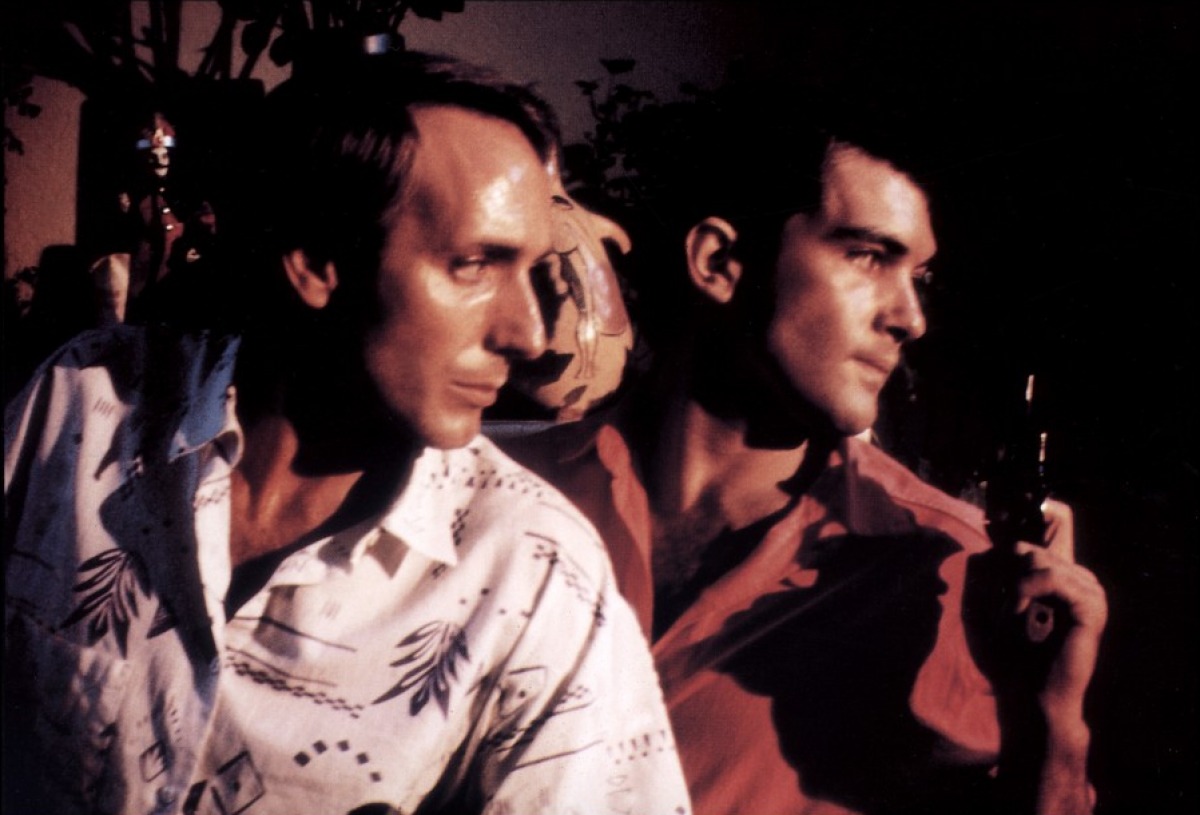

Tie Me Up, Tie Me Down (1989) revolves around a former porn star (Victoria Abril) falling in love with her creepy, sexually obsessed kidnapper (Antonio Bander). Kika features an eight-minute rape scene that’s played for comic effect. Talk to Her’s conclusion arrives as *spoiler* Benigno’s impregnates the comatose Alicia and is sent to prison, Alicia awakening after a miscarriage *end of spoiler*.

Yet what’s missing in these simple descriptive analyses written above is a contextual reading of Almodóvar’s intentions. The titular character of Kika refuses to let herself be defined by the incident, and becomes a stronger character by force of her will.

Almodóvar deconstructs the scene visually as it plays out, showing us the POV of a voyeur camped on the other side of the apartment block who watches the crime play out. It is he who calls the police, but they themselves are bumbling nobodies without much interest in the crime; the comic punch of the film is aimed squarely at these surrounding figures rather than Kika herself.

Then there is The Skin I Live In, which at its root is a film that is deeply concerned with the lingering effects of sexual violence. In fact it is the catalyst for almost the entirety of the film’s plot, and it is a deeply psychological investigation of how such tragedies can traumatise and tear apart not just its immediate victims, but their families and friends too.

In Talk to Her, Benigno’s crime is fiercely one of passion, borne out of a misguided romantic and sexual obsession with the object of his desires. It is a film that goes deep into the meaning of devotion and of obsession, drawing the lines and parallels between both.

In this case, it is not used as a glib plot point, but the prime logical endpoint of Benigno’s obsession. The film has been criticised for its empathetic portrayal of its lead character, but to do so is to miss the point. Almodóvar always gives the utmost respect to his characters, whether they are gross criminals or generous saints, which leads us nicely onto the next point…

8. Forgiveness and empathy to even the worst people

Few directors are as keen as Almodóvar to give a fair hearing to each of his creations. We have already talked of Benigno’s case, and it is true that Almodóvar allows him to state his case. That we realise the awful nature of what he has done yet are allowed so close to an understanding of his mental state is part of what makes the film so compelling, heartbreaking and tragic.

The multiple potential villains of The Skin I Live In are also treated with empathy and understanding, again giving the film a levity and emotional gut-punch that allows it to surpass its B-movie plotting.

Many of the main characters of All About My Mother spend much of the film complaining about Lola, but her eventual appearance in the film is burdened with tragedy and empathy and humane touch. Even the more lurid films of Almodóvar’s, like Matador, The Law of Desire, and Live Flesh are touched with that empathy and humanity.

Throughout his work, Almodóvar always shows empathy and forgiveness to even the absolute bottom of the barrel of humanity – very Catholic – and one senses that despite his secularity, he has respect for the concept of religion, belief and faith, and in particular admires the forgiveness that is so central to Christian and Catholic teaching, even if it isn’t always practiced by its preachers.

But Almodóvar does practice it, and this is perhaps one of the most liberating elements of his work. It says ‘don’t worry, you are welcome here, no matter who you are’, and this underlying positivity to his work gives it the vitality and energy it so brilliantly uses to mark out the wonderful world of Almodóvar.

Author Bio: Fedor Tot is a Serbian-born, Welsh-raised history undergraduate at the University of East Anglia. Outside of an interest in cultural histories and particularly those of the old Yugoslavian homeland, he is also an occasional standup comic, most trading in jokes about spatulas and socialism. You can visit his personal blog here.