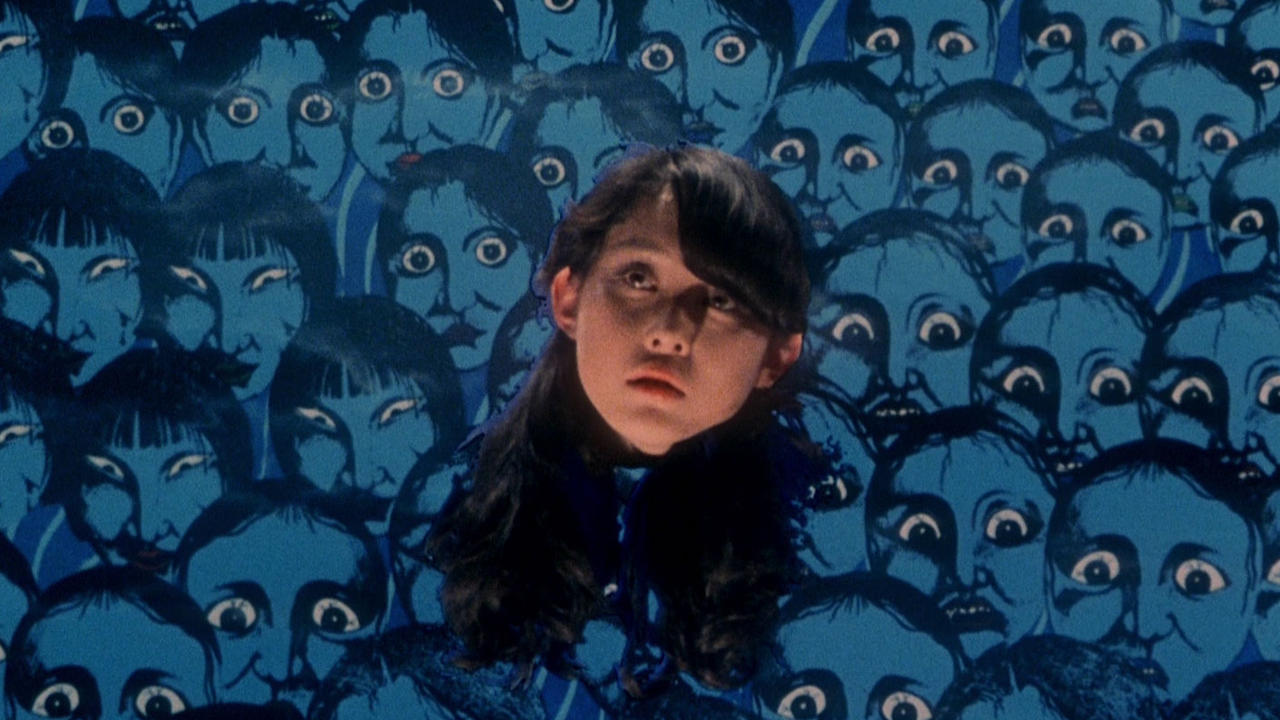

7. House (Nobuhiko Obayashi, 1977)

Probably the most incoherent entry on the list due to its surrealistic fashion, “House” derives from a script considered so absurd that at the time, no director would take it on in fear of ruining his or her career. Nobuhiko Obayashi, however, wanted to direct it since he initially read it, a plan he accomplished two years later.

Accordingly, in 1997, he directed this film about seven girls that visit a peculiar house during their summer vacation. The building is revealed to be a living entity, as it kills the girls in the most absurd and surrealistic way to appear in cinema, up to that point.

Obayashi creates a perverse and ingeniously maladjusted interlude that barely fits into the cinematic frame, and constantly transforms from a supernatural thriller to a slapstick comedy and vice versa, where the special effects “flirt” with drollness, due to their absurdity.

According to him, the film was a tribute to his friends lost in the atomic explosion.

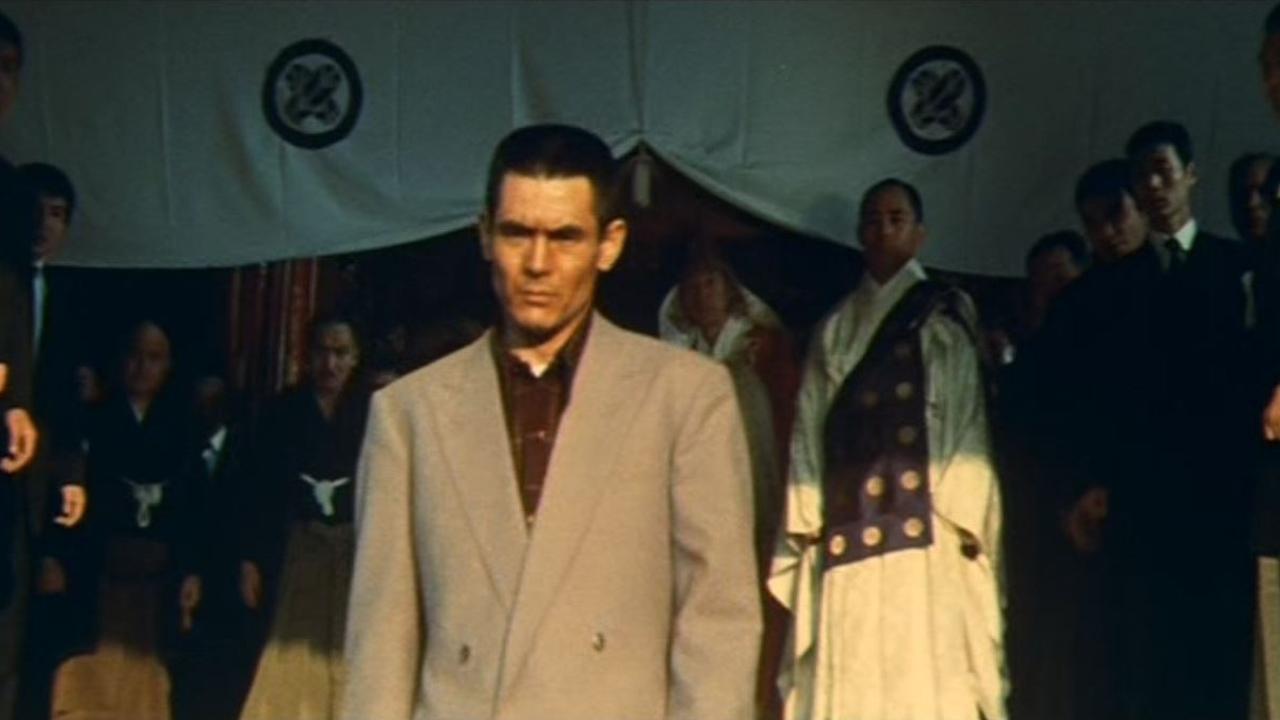

6. Vengeance is Mine (Shohei Imamura, 1979)

The film is based on the homonymous novel by Ryuzo Saki and depicts the true story of the murdering spree of serial killer Akira Nishiguchi (Iwao Enokizu in the film).

Through a number of flashbacks, the script focuses on Iwao Enokizu’s character, a worker and small-time criminal, who kills two of his co-workers and then embarks on a psychopathic trip of rape and murder. Misleading society and the police, he assumes various identities as he becomes entangled with a convicted murder and her mother, who owns a hotel.

Shohei Imamura directs a film that manages to focus on a single individual for 140 minutes, without analyzing him or giving a reason for his hideous actions. His purpose is to show the extremes humans can reach, even without knowing the reasons themselves.

Ken Ogata is magnificent in the protagonist role, portraying a true sociopath who does not stop at anything in order to achieve his goals.

5. Dodes’ka-den (Akira Kurosawa, 1970)

The film is based on Shugoro Yamamoto novel “The Town Without Seasons” and was Akira Kurosawa’s first color movie. Despite being nominated for the Oscar for Best Foreign Language Film, it was a financial failure and eventually led the already depressed filmmaker to attemp suicide.

The film focuses on the lives of a variety of characters that live in a rubbish dump. Roku-chan is a mentally challenged boy who fantasizes that he is a tram conductor. The rest of the characters include children who try to help their parents by begging in the streets and a number of individuals who dream of escaping their poorness.

Kurosawa directed a film in a way he was not used to, including the fact that it was shot in only nine weeks, and without his regular protagonists. In that fashion, his distinct editing techniques and compositions were nowhere to be found, with Kurosawa focusing on depicting the hideous environment of the protagonists with the most vivid colors.

However, “Dodes’ka-den” is another in-depth analysis of human nature and the lyricism is, once more, evident, as are the many allegories regarding Japanese capitalism in contrast with traditional values.

4. Belladonna of Sadness (Eiichi Yamamoto, 1973)

Mushi Productions, a company created and abandoned by Osamu Tezuka, (aka “God of Manga”), produced the adult-themed anime “Belladonna of Sadness” in 1973. It was the final part of a trilogy named “Animerama”, a commercial failure that kept the title in anonymity for many years.

The script is based on Jules Michelet’s novel on the history of witchcraft, “La Sorciere”, which was published in 1862 in France.

The story revolves around a young couple named Jean and Jeanne, whose happiness ends during their wedding night, due to Droit du seigneur, a feudal law that allowed local lords to be the first to deflower the bride. That night, the local baron and possibly his lackeys rape Jeanne.

She and her husband try to forget what happened, but Jeanne is still tortured by the fact, which is personified as a demon of phallic form, who appears in her sleep. These memories have complicated results, since the demon does not only scare her, but also makes her feel pleasure. Furthermore, he encourages her to exact revenge from the baron, as he suggests that the only way to accomplish that is by making a deal with the Devil.

“Belladonna of Sadness” is the most serious and most avant-garde part of the trilogy, with the story unfolding chiefly through narration rather than dialogue, and with animation on top of static, panoramic paintings, influenced by Art Nouveau artists such as Klimt and Beardsley, and Tarot illustrations.

The feast of colors becomes evident from the first second, as is the case with the attention to the detailed depiction of the characters and their surroundings. The overall design by Kuni Fukai is close to perfect, with each shot looking like an actual painting.

The animation by Gisaburo Sugii is of equal quality, as the movement seems like flowing from the static images, giving life to the paintings. His choices on what will remain static, when there will be motion, and how the outcome will remain natural, are unmistakable.

3. Dersu Uzala (Akira Kurosawa, 1975)

This Soviet-Japanese co-production was the winner of the Best Foreign Language Film Oscar in 1975. Furthermore, the film reinvigorated Kurosawa’s career, which was in shambles after the financial failure of “Dodes’ka den”.

The film revolves around the friendship of Arsenev, a Russian official in charge of an exploration in Siberia, and the titular character, a seasoned sherpa who acts as the mission’s guide.

Kurosawa films the Siberian cold in the most horrendous fashion ever. The cold is actually an enemy, almost a physical presence, in front of which humans cannot do anything but stand in awe. In that fashion, Kurosawa depicts the effects of the physical world upon the individual, as he exemplifies male friendship.

2. Battles Without Honor and Humanity (Kinji Fukasaku, 1975)

Kinji Fukasaku would secure a place in the history of Japanese cinema with his five-part saga “Battles Without Honor and Humanity”, which revolutionized the Yakuza genre.

The films adapt a series of articles by journalist Kōichi Iboshi that ran in Weekly Sankei that were rewrites of a manuscript originally written by real-life yakuza Kōzō Minō while he was in prison.

The story takes place mainly in Nagasaki after World War II, where an ex-soldier named Shozo Hirono tries to sustain his own small gang, among power struggles between the largest Yakuza groups.

Filming in a way that gave meaning to the title, Fukasaku stripped the genre of any heroism, portraying his characters as radically evil and the Yakuza life for what it really is, even including the role of politicians.

Furthermore, his stylized depiction of violence found its apogee in these films, with the extensive though skillful use of hand-held camera and the constant action scenes where hyperbole is the rule.

Bunta Sugawara is the undisputed star of the series, giving magnificent performances as Hirono, in distinct cult style. Among the many actors that participated in the pentalogy, cult favorites Sonny Chiba and Meiko Kaji stand out.

1. In the Realm of the Senses (Nagisa Oshima, 1976)

“In the Realm of Senses” is one of the most controversial movies in the history of cinema, with critics and fans still debating if it is of high artistic value or just pornography.

Nagisa Oshima based the film on the true story of Sada Abe, a woman who in 1936 erotically asphyxiated her lover and subsequently proceeded to cut off his penis and testicles and carry them in her kimono. The movie describes the relationship between Sada Abe and Kichizo Ishida, a hotel owner, through a plethora of erotically perverted scenes, up to its tragic conclusion.

Furthermore, solely excluding the mutilation scene, the rest of the erotic scenes incorporated actual sex, including fellatio and an orgy with geisha using sex aids.

However, beyond its evident promiscuity, Oshima managed to present, inside a claustrophobic setting, an erotic affair of intense paroxysm, a manifestation of love that surpassed the borderline of the extreme.

Through this permeating extremity, Oshima eloquently depicted one of the main characteristics of Japanese culture: the ambiguity that results from the love for everything extreme and the shame for this love, which even manifests through the laws of the state.

Author Bio: Panos Kotzathanasis is a film critic who focuses on the cinema of East Asia. He enjoys films from all genres, although he is a big fan of exploitation. You can follow him on Facebook or Twitter.