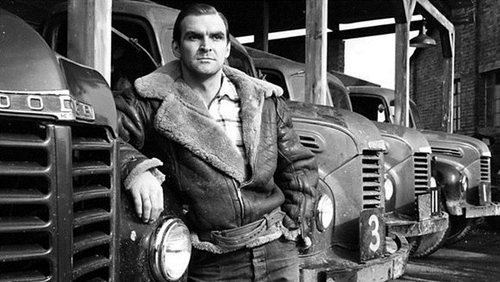

5. Hell Drivers (Cy Endfield)

Hell Drivers is a fascinating hybrid of bold American-style direction and stoic British realism. Its director, like Jules Dassin, had come to the UK after a run-in with McCarthyism. Desperate for work, he took this paltry little B-thriller by the scruff of its neck, filled it with one of the most extraordinary casts found in any British film, and gave it a heft it probably didn’t deserve.

The plot couldn’t be more prosaic – truck drivers working for a haulage firm risk life and limb, racing each other down narrow country lanes for an extra slice of the bonus. But those truckies are Stanley Baker, Patrick McGoohan, Sean Connery, Sid James and Herbert Lom, all young and before-they-were-famous, eager to make their mark and so attacking the material with gusto. And their boss? That man, William Hartnell, again, himself on the brink of his most famous starring role.

The whole thing should be pathetically small potatoes, but it fairly crackles with energy, the driving sequences reaching a delirious fever pitch. Endfield would go on to make the much-loved Zulu, but this is arguably his most intriguing British work.

4. It Always Rains On Sunday (Robert Hamer)

Robert Hamer was the bright new hope of British film in the 1940s, but alcoholism got to him, and by the end of the decade, after the uproarious success of his best-loved film, Kind Hearts and Coronets, his talent had drained away.

But it’s worth revisiting this earlier effort, featuring a typically impressive performance by Googie Withers as a bored working-class housewife, plodding dutifully along in a dreary, grey, terraced-house hinterland, only for a long-lost ex to turn up and ask her for shelter from the police.

The old flames of desire and romance flare up for a brief, exciting moment, only to be cruelly extinguished, as the man is caught and ordinary life resumes its grip on her

. It’s arguably the most despairing film in this noir cycle, precisely because the misery it portrays is so close to that of the majority of its audience. But as a sympathetic portrait of ordinary people’s contemporary situation, it has seldom been matched in any other genre or national cinema.

3. Brighton Rock (John Boulting)

Brighton Rock is principally remembered as the film in which cuddly luvvie, Richard Attenborough, managed to act against type and provide a genuinely convincing portrait of evil (though there is his turn as serial killer John Christie in 10 Rillington Place).

Pinky, a local Brighton knife-boy, is less a gangster than a dangerously troubled, overgrown adolescent; Attenborough invests him with enough complexity to make him an arresting figure. But there’s also William Hartnell, the first ever Dr Who and veteran of umpteen war movies, setting aside his usual crusty patriarch routine and delivering a fascinating turn as Pinky’s sidekick, using a blade to dig out the dirt under his nails, casually spitting on a rival’s carpet.

A product of its time, the film can’t hope to fully recreate the bleakness of Graham Greene’s original story, but it makes for intelligent entertainment, and the stench of tacky seaside fish-and-chip shops and sweaty pubs seems to infuse its night-time photography.

2. Night and the City (Jules Dassin)

This is a story of two Americans on the run and on the make – one is Richard Widmark’s Harry Fabian, a small-time hustler trying to get into the wrestling racket against the wishes of his competitors, and the other the director Jules Dassin himself, fleeing the HUAC Committee and attaching himself to this nifty UK potboiler as a way to keep making a living.

There are two versions of this film, made for the British and American markets respectively, and ironically it’s the latter which is superior. More tightly edited and more pacily scored, it offers an exhilarating odyssey through a bizarre underworld in which pathos, skullduggery and the grotesque are common bedfellows.

Despite the violent retribution looming on all sides, Dassin finds time to make the relationship between Harry and his grizzly partner genuinely touching, and the final meeting Harry has with his girlfriend under Hammersmith Bridge is one of the most moving and romantic in all noir. It’s a film – like its director and hero – in hiding; a masterpiece disguised as just another thriller.

1. The Third Man (Carol Reed)

It’s ironic that the best-known film in this series actually came towards the end of the British noir cycle, and is in many ways the least typical (and arguably the least interesting).

A self-consciously Hollywood style production, with big-name American stars, Joseph Cotten and Orson Welles, it often seems like an attempt to imitate the latter’s directing style – with canted angles, long-held deep focus shots et al – while its story of a man trying to discover the truth about his vanished friend from a series of witnesses and adversaries apes the structure of Citizen Kane.

But there’s no doubt that this story captured the public’s imagination, leading to a successful radio spin-off during the ’50s, and that, in Harry Lime, Welles delivers an unforgettable creation, not least in his renowned “cuckoo clock” speech, which sums up a whole philosophy of cynicism in one easy soundbite.

Reed deserves credit for his portrait of war-torn Vienna and his often inspired use of location – framing Lime in a darkened doorway, and Alida Valli in long shot on the path out of a cemetery. Most memorable of all is the zither score by Anton Karas, both cheeky and wry, yet full of yearning at the same time.

Author Bio: Mike is a freelance film writer, currently living in London, who has written for the BFI Screenonline database, Moviemail and horror movie site, Zombie Hamster. He also subtitles TV and films for the hearing-impaired and prepares audio description for the blind.