8. Holy Motors (Leos Carax; 2012)

Leos Carax’s psychedelic film depicts one day of Oscar (Denis Lavant), a strange figure who jumps from one alternative life into another. It is as if he were acting, but there is no stage or camera visible in the frame – apart from the one that operates as our eyes, the audience’s point of view to give an insight into this silly, bizarre and playful world.

Leos Carax’s film is a meditation on the role of cinema today. As The Sleeper, Carax wakes up at the beginning of the film to enter a packed movie theatre where the audience is fast asleep. Carax’s audience is not one that would be mesmerized by the film; this crowd sleeping in the dark room is already familiar with the shocking twists of Fincher, Lynch or Christopher Nolan.

The new language that slowly travelled from art film into popular cinema cannot shake them up anymore. Oscar’s answer to the question what keeps him going is simply: “The beauty of the act”. Oscar, in his many roles is the film industry itself, always trying to do a bigger blast than the previous one to keep the audience interested.

Carax’s self-referential film is a brilliant criticism of the world of contemporary art and the constantly insatiable audience that always craves entertainment. What is the best: Holy Motors itself is a totally lunatic, but awfully entertaining piece of art that is guaranteed to surprise and satisfy its audience.

7. That Obscure Object of Desire (Luis Bunuel; 1977)

As an auteur, Bunuel is widely known for his uniquely surrealist mise en scene. His surrealism does not derive from the bizarre, dreamlike objects or characters that we can see in Michel Gondry’s films. On a visual level, Bunuel operates with realistic, in some cases almost naturalistic style; it is the situations he puts his characters through and their verbal or physical reactions that are surreal, bizarre and shocking.

His last film, That Obscure Object of Desire, is a study of the extremes of human desire. Mathieu (Fernando Rey), a rich, elderly man, who falls in love with his beautiful young maid, Conchita (Carole Bouquet, Angela Molina). His love turns into an obsessive desire to possess her, while the girl plays with Mathieu’s longing and physical cravings to satisfy her one desire: wealth. The narrative structure of the film is not that unusual: the story is told in flash backs.

However, it is a puzzling specialty that Conchita is played by two different actresses. They take turns to play the role in alternate scenes, and occasionally switch places in the same scene. Even though this solution was the result of an unfortunate event (an argument between the director and the originally casted actress resulting in her leaving the project) it is a key element of the film that elevates the ‘object of desire’, Conchita, to a universal level – to stand for all women and sexuality.

6. Memento (Christopher Nolan; 2000)

Thanks to its key memes, film noir is an ideal genre for mind-twisting plots. A mysterious death needs to be uncovered and the audience follows the investigation from the point of view of the detective. However, the detective’s hypothesis of the case is often based on fragmented information, which might mean that as the film develops, the audience has to revise their own hypothesis of the crime case’s solution.

In Memento Christopher Nolan brings the obscure noir narrative to perfection and combines it with his solipsistic perspective which establishes what we today recognize as his auteuristic style. The audience is not simply misled by the fractional information the central character beholds of the case, but is forced to question the trustworthiness even of the fractions related by this character.

Leonard (Guy Pearce) is on the hunt for the murderer of his wife, but in order to remember the clues of the case he has to use a strange method. As a result of the tragedy he lost his short-term memory, so he keeps a record of all key information as a tattoo on his body.

The nonlinear narrative of Memento follows two storylines: led by Leonard’s fragmented clues we travel back in time towards the moment of the murder, while another, black and white storyline moves forward in time and follows Leonard from an outsider’s point of view. This has the potential to overwrite everything the audience presumes about Leonard.

5. Fight Club (David Fincher; 1999)

David Fincher’s cult-classic is a film that could easily be featured on the list of the best adaptations as well. While apart from the ending he stays loyal to the plot of the book, not only following the storyline, but also successfully transposing its elliptic structure into film. Fight Club is a visual deep-dive into the troubled mind of the 20th century Americans, a society where comfort resulted in way too much oppressed anger.

The film’s unnamed narrator (Edward Norton) finds a way to cure his insomnia and anxiety by attending various support groups pretending he has the issue the others there are suffering from. However, this offers him only temporary relief and after his apartment is blown up, he gets in touch with a soap salesman, Tyler (Brad Pitt), who he met on a plane trip. The two men arrange a fight club where the frustrated everymen can engage in a fistfight.

As the club gradually grows into the anti-corporate Project Mayhem, the link between the narrator’s suspicious relationship with Tyler and his personality disorder becomes more evident. The film’s non-linear narrative and convoluted cross-references prepare the audience for the unexpected twist from early on, but at the time of its release the climax of Fight Club was simply jaw-droppingly shocking and brilliant.

4. The Shining (Stanley Kubrick; 1980)

Kubrick’s masterpiece with a legendary performance from Jack Nicholson in an unfathomable story, forcing its audience to constantly revise their reading of the scenario and yet, never being able to come up with a final solution. Similarly to Mulholland Drive, the best thing one can do is to sit back, relax, and let the smart storytelling and unexpected twists mesmerize them.

Although Kubrick’s adaptation of Stephen King’s novel has been criticized by some for altering the book’s storyline in some places; what he really did was elevating the characters to an archetypical level. Instead of a horror about wicked ghosts, Kubrick’s Shining has become a film about Evil itself.

Jack Torrance (Jack Nicholson) arrives to the haunted Overlook Hotel with his family as a winter caretaker, aiming to use the solitude of the closed hotel for writing. While the eerie place is haunted by the spirits of mysterious murders, Jack is haunted by his own dark spirits: his incapability to write, his alcoholism, an unhappy marriage and the ambiguous relationship with his son. As he goes to war against all these spirits, a final twist irrevocably overwrites all our previous assumptions.

3. Persona (Ingmar Bergman, 1966)

In Ingmar Bergman’s films, the visual and verbal layers can both be symbolic and literal at the same time. His style is a mixture of theatrical realism and existential philosophy; where, from time to time, the screen image loses its connection to reality but only to allow the characters’ inner world to surface. His preferred format is closed-situation drama where the characters’ relationships to each other are depicted through their action as much as their spatial movement in their physical surroundings.

In Persona, Bergman examines the conflict between the Artist and the mundane, everyday life; the former embodied by Liv Ulmann and the latter by Bibi Andersson. The film introduces Elisabet, the actress (Liv Ulmann), as she becomes hospitalised following a breakdown on stage which left her mute. Despite the facial similarity, her carer Alma (Bibi Andersson) appears to be the exact opposite of the broken and passive Elisabet: chatty, naïve and light.

The two women travel to the countryside in the hope of nature having a healing effect on Elisabet. Initially Alma’s chatter seems to soften Elisabet’s enclosure; however, her passive silence can equally suggest ignorance. In a dramatic dream scene that follows Alma’s confiding in Elisabet, the faces of the two women become one, signifying the break in Alma’s naïve view of life which also marks a silent inner fight in between the two woman.

However, this is not only the clash of two opposite personalities. This psychological study of the two woman is also Bergman’s attempt to answer a key question: is it possible for the modern artist to accept the emptiness of everyday life? The director’s answer is a peace-treaty. The Artist has to accept the everyday in in order to be able to produce art.

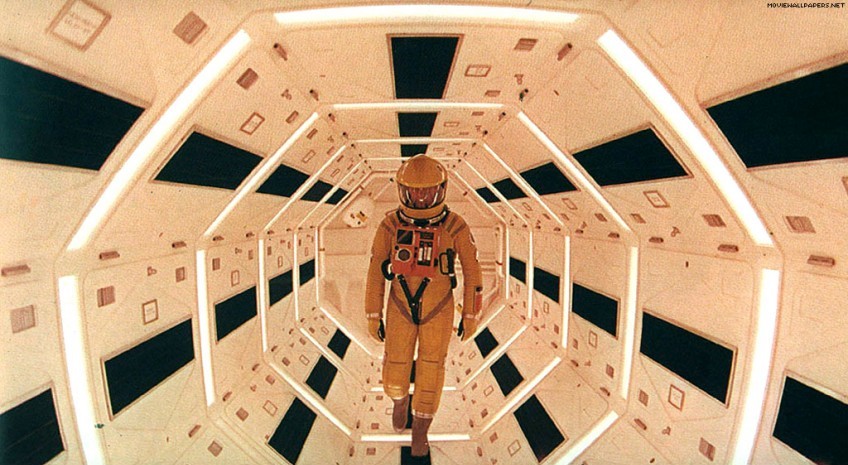

2. 2001: A Space Odyssey (Stanley Kubrick; 1968)

Kubrick’s 2001 Space Odyssey is film poetry at the highest level. Its poetic nature is not the same as that of Tarkovsky’s Solaris – also inspired by 2001 Space Odyssey. While Solaris is a deeply philosophical, transcendental science fiction with a strong psychedelic power, Kubrick created the first big budget sci-fi that influenced blockbusters such as Star Wars, Alien and Blade Runner.

Several scenes of the epic, and almost completely dialogue-free film survived as standalone memes such as the dance of spaceships to the tunes of Strauss’ music, the opening scene with the monolith as the camera switches from a bone tossed in the air onto a space ship, Halo, the vicious, manipulative A.I. or the grand finale.

2001: A Space Odyssey is a film that could be the topic of endless nights of debates over the Nietzschean references or the philosophical meaning of the monolith, but that is not its primary significance. 2001 Space Odyssey is a mesmerizing extra-terrestrial ballet, the most beautiful film ever made.

Even though it is supposed to be a slow movie, the graceful harmony of the eerie music and elegant images are so hypnotic that one will hardly have time to realize before the end credits would crawl into view that the movie had no traditional plot.

1. Mulholland Drive (David Lynch; 2001)

Even though Lynch’s distinctive style defines him as an auteur, he moves around with ease in the realm of genre films; thus positioning him on the border of art film and Hollywood movies. Mulholland Drive is an excellent example of how the cryptic narrative of 60s modern art film partially influenced popular Hollywood films of the millennia.

This mystery film noir introduces several story lines that intertwine, connect or cross each other’s paths, forming a head scratching puzzle. However, unlike the enigmatic plot twists of classic film noirs, this riddle is not one that the audience is expected to solve.

The twisted storyline of Mulholland drive is art for art’s sake. It is a brilliant author’s ironic game with film genres and our preconceptions of crime film, melodrama or film noir. Thanks to the bravado of Lynch the exaggerated, melodramatic entrée of Naomi Watts (Betty) is as sullen as the episode when a man tells about his nightmare at a Winkie’s.

The grim, yet ironic air surrounding the key moments of the film already suggests the audience that this story can’t be deciphered based on any pre-existing knowledge of genre films, also hinting about the key twist that will peremptorily mix up the plot lines.

Author Bio: Melinda Gemesi has been a freelance film critic since her second year as a Film Studies Student. She holds an MA in Film Studies and Online Journalism and is currently living in London. In her free time she is working on a literary project about which you can find out more on thestoryhunt.tumblr.com.