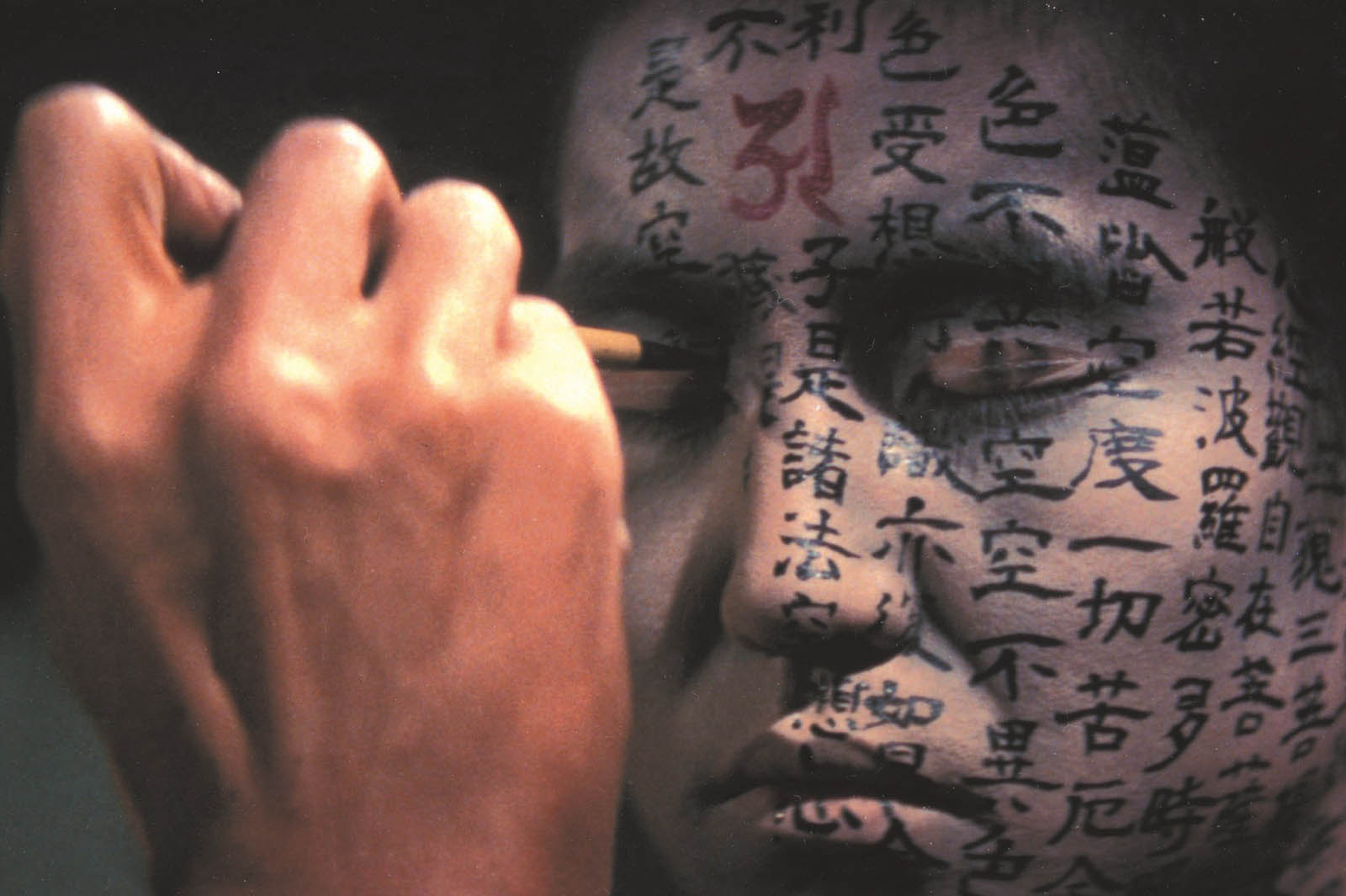

8. Audition (Takashi Miike, 1999)

Takashi Miike’s Audition is a heartless, brutalistic, misanthropic film, but then none of those things are necessarily detriments when horror is on the mind, are they? Especially when they’re composed with the elegance and cruel craftsmanship of Miike’s 1999 horror opus about gender relations in modern Japan.

It leans heavily on “creepy, succubus woman” stereotypes, admittedly, although its larger narrative is more a critique of the sort of hyper-repressive masculinity Miike sees in Japanese culture that would make it reasonable for a man to “audition” wives he doesn’t know. But Miike’s genre-busting critique of the intersection of male privilege and stuffy, clinical corporate culture in modern society works as a piece of filmic manipulation too.

He dares us to see the first half of his work as a classical romance (and thus mocking us and implicating us in wanting to see lead star Ryo Ishibashi succeed in his oppressive scheme to turn romance into a corporate interview process).

Dry humor abounds, but in the second half of the film Miike flips things on their head and reveals Ishibashi’s selfish greed and oppressive male privilege to be his undoing in the form of an avenging female as much angel as demon. Her lack of humanity doesn’t really do much to humanize her and can cripple the film as a feminist text depending upon one’s interpretation of “feminist text”, but the horror credentials, especially when Miike reveals his painterly use of non-moving, quiet spaces in between blood-curling shocks, are superlative.

7. Kwaidan (Masaki Kobayashi, 1964)

Kwaidan is unique in the mid-60s Japanese ghost story explosion for its vibrant color cinematography, and in director Masaki Kobayashi’s understanding of this fact’s importance. He places color at the center of every tale in his omnibus (anthology) horror, moving between pulsing blues to furious reds to sickly yellows to piercing whites with an animator’s understanding of space and contrast.

He creates four stories that seem to exist in the mind, emphasizing their constructed, tall-tale spiritualism by giving the environments the patchwork feel of dioramas and draping the film in painted-on textures that belong more in the world of theater than film.

One particular moment, where he paints the background sky with eyes that observe and threaten his character’s sanity, combines with his pushing the sound forward in the mix so that it spreads out over the screen and coats it in a blanket of eerie woe, to create a sensation of the film surrounding his characters and strangling them dry with ever-watchful fear.

These four stories and their themes of loneliness, guilt, temptation, and the sins of the past latching onto the present are easily transcribed to any time period, but Kobayashi’s specific vision is entirely at the intersection of Japan’s past and future.

6. Hausu (Nobuhiko Obayashi, 1977)

Many films look to the word “unique” as a selling point, but few films see the word existing down to their deepest and darkest cores like Nobuhiko Obyashi’s Hausa. A stew of equal parts old school Universal chillers, Japanese ghost theater, kitschy martial arts, and a mind-melting cinematic toybox of tricks and treats big and small, Hausu exists in a world of its own, and it turns that world inside out too.

Every scene brings a new trick, from color-coded cinematography where “coloring inside the lines” seems to be a guideline more than a hard rule, to superimposition that exists for the sake of itself, to background paintings that emphasize their hand-drawn whimsy over their realism. It is a true grab-bag of film’s past and future, a culture-mixing pot Obayashi dives into with vivacious, dashing exuberance. There’s no kitchen sink, but there is a piano that eats humans. A fair trade-off, no?

5. Ugetsu (Kenji Mizoguchi, 1953)

Kenji Mizoguchi’s most potent achievement, and arguably the crown jewel of Japanese cinema whole-sale, the quiet sigh of Ugetsu burrows into our eyes with plaintive visual beauty and splendidly cavernous, all-encompassing sound design, both of which refuse to leave when the film nominally comes to a close.

Everything here, from Mizoguchi’s fog so thick it clouds the human mind to his crawling, never-resting lateral camera movements, seems to slide off the screen and permeate the air around an unsuspecting audience. It is not scary in the traditional sense, but its ghostly visuality and transfixed, almost possessed, camera matched to brutal, hypnotic silences grow and fester in the mind. Many horror films aim for something psychological in their scripts.

Ugetsu is one of the few that feels like it can truly claim to exist in a state of the mind, melding the physical and mental, the external and the internal, until they become one. It attains a disturbed, singular hypnosis all its own.

4. Onibaba (Kaneto Shindo, 1964)

Onibaba, probably the most famous of the mid-60s Japanese ghost story glut, feels a tad undernourished compared to its successor Kuroneko, but many of the techniques that would set that film alight burn brightly here as well.

The story of two women, played by Nobuko Otowa and Jitsuko Yoshimura, who kill two soldiers during a war and steal their possessions, Onibaba sees the trend of high moralism evident in most J-horrors ready to come out and play. It’s a cursed, troubled film about the past coming back to haunt you (the de facto theme of Japanese horror in the 50s and 60s), positing an undying humanity that always returns for revenge.

Director Kaneto Shindo connects the spiritual with the tangible through noirish shadowplay, sublime hard lighting, and absolutely unimpeachable sound design that captures everything from hard screeches to weary, soul-deep moans to the crushing bullet-hell of the rain ever-pounding and leaving no one safe in silence.

Hikaru Hiyashi’s score is also an all-time bone-chiller, blending tribal drums that refuse to go down easy with all sorts of unnaturally enhanced everyday noises and wrapping them all up in a bun of jagged symphonics and a darkened choir that reaches directly into our innermost worries.

3. Tetsuo: The Iron Man (Shinya Tsukamoto, 1989)

Shinya Tsukamoto’s infamous 1989 dissection of film history and hallucinatory nightmares is one of the few films that genuinely deserves the claim “fever dream”. Following the vaguest narrative – a man kills a passerby who had shoved a metal bar into his leg, shows no remorse for the killing, and then steadily finds himself transforming into a metal man – the fundamental scene-to-scene bones of the film play out with such slapdash mania they cannot but approximate Tsukamoto’s idea of an acid trip gone wrong.

The sharp black-and-white cinematography, garish lighting, and absolutely destructive editing do everything in their power to render narrative cinema inconsequential and hopelessly stranded in the face of Tsukamoto’s vision, which takes the traditions of Japanese horror – an emphasis on moral guilt and remorse as the foundation for horrors big and small – and does everything in its power to make them as deranged as possible.

The nails on a chalkboard musical antics, almost all of it based in machinery, and the relentless stop motion to emphasize the way pure metal is taking on a life itself and overpowering the film help immeasurably to this effect as well.

2. Empire of Passion (Nagisa Oshima, 1978)

Nagasi Oshima’s follow-up to his infamous In the Realm of the Senses fully develops his spirited pet theme, the intersection of sex and power, with uncommon potency and a formidable id, boiling base-level human drives to a seething passion that explodes in feverish self-destruction and limber lust. Yet any who mistake his propensity for sex and nudity for the makings of a sensual film are mistaken.

Empire of Passion’s story of two lovers intertwines love with psycho-sexual control and wraps both in revenge-fueled filmmaking that manages to call on the Japanese ghost stories of the 60s for mythic visual iconography while advancing their study of guilt and gender by more openly recreating its lover’s heated histrionics on screen. It’s a surfeit of sweat in the guise of a film, and it enhances the classicist theater tragedy at the core of most Japanese horror to match the more existential horror of the piece.

1. Gojira (Ishirō Honda, 1954)

The Godzilla series has become such a wet blanket over the years, it’s easy to forget the beautiful quilt of modern machination and atomic fallout that is Ishiro Honda’s worried social parable Gojira. With the titular thunder lizard looking more like a burn victim than ever again and some pristine black-and-white destruction indebted more to Expressionism than you’d think, Gojira is a ferocious film intermingling death and life in ways that are both depressingly concrete and glowingly abstract.

Its script can be a tad on the loquacious side, but it’s saved by the astounding bluntness of some of the dialogue, which explicitly takes WWII and the bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki to task without any masquerade of sci-fi buttoning-up. Gojira is real-world horror through the fatalistic fable that is the filmic lens, but it’s no grand facade that looses track of its core dialectic of anger and melancholia. Everything that seethes and burns within is right there on the surface for the taking.

Author Bio: Jake Walters is a recent graduate of Amherst College and an aspiring film-writer/ist. He shares his thoughts on film at his website, thelongtake.net and is particularly interested in film in relation to society, race, class, and gender, He writes frequently on horror films and looks to Werner Herzog, Michel Foucault, and John Shaft for life advice. You can find him on Twitter@long_take.