9. Rome, Open City (Dir. Roberto Rossellini, 1945)

World War II was one of the most horrific events in human history, leaving many countries in shambles and families destitute or in extreme physical and/or emotional pain. One country to take an especial hit from the war was Italy. Towards the end of the war, it seemed that the Italian Film Industry was crumbling and would never recover. But 1945 saw a new hope for the struggling Italian Cinema, which came in the form of Roberto Rossellini’s Rome- Open City.

Rome, Open City saw the birth of the Italian Neorealist movement, a series of down and dirty films that were decidedly political and which had the goal to depict the hardships of life in post-WWII Italy. It was at this point where cinema became a medium that would respond to the filmmaker’s world without being propaganda or documentary.

It also became the first major cinematic film movement and as such gave cinema another connection to the other arts and separated it from other commercial forms. Rome- Open City is the key film of Italian Neorealism, as it sets up everything that what was to come from the movement. On top of that, it is simply a great movie.

Beyond being part of a defining film of an influential movement and a time capsule for the state of mind that Italians were in after WWII, Rome- Open City is filmmaking at its highest form. Rossellini didn’t have a budget and the only professional actor was his then lover, Anna Magnani, who at that point was an unknown. All other actors were non-professional, a tactic that continues to be viewed as unconventional.

As stated previously, this film was shot in a very down and dirty manner on cheap film stock, in large part due to budget concerns. The result gives the film a very disgusting and impoverished look, something that reflected the conditions of Italy. This is also a lesson that film students could learn from when making their films, as Rossellini worked with his budget instead of against.

The film itself is the purest depiction of the human condition ever committed to film. Rossellini gets up close and personal with his characters and it becomes easy for audience members to sympathize with their situation and struggle, despite knowing the destined horrors that await them.

10. Tokyo Story (Dir. Ozu Yasujiro, 1953)

The films discussed on this list, up until now, have had the goal of pushing the boundaries of cinema through groundbreaking techniques and flashy style. Ozu Yasujiro was not one of these filmmakers. Instead, his films were reflections or meditations on cinema and reduced it to its simplest form, basic human dramas. But, as with Roberto Rossellini, the second half of Ozu’s career was affected and changed as a result of the events in WWII, specifically the Hiroshima Massacre.

Ozu’s films became more melancholy and used the effects of the war as a backdrop, which is unlike Rosselini’s films, which had the effects in the forefront. As a director, Ozu had a very strict style. He was infatuated with long takes and his camera was always low to the ground.

His camera never moved and the scenes would transition only through a hard cut to an inanimate object. Instead of using over the shoulder shots during dialogue scenes, Ozu placed the camera smack in the middle of the conversing, so as to put the viewer in the center of the conversation. Knowing all this, it is appropriate to discuss Tokyo Story: Ozu’s most important and best work.

Tokyo Story tells the story of an aging couple who travel to Tokyo to visit their three grown biological children and their widowed daughter-in-law, whose husband died presumably as a result of the war. While the three biological children and their grandchildren seem to not want to deal with them, their daughter-in-law gladly takes them in and goes out of her way to show them around the city. It is examination of the family dynamic, something Ozu obsessed over throughout his career.

A key element to the film is the choices characters make. While characters make bad and/or selfish choices, their character is fully fleshed out so it is understood why they made these decisions. At the center of all the bad decisions are two characters that are impartial in their way of looking at the situation and look at things practically and as objectively as possible. This leads to the audience questioning whether the decisions were bad at all or merely inevitable.

Tokyo Story is a triumph in filmmaking from one of cinema’s very best masters. It reminds audiences that a film does not need to be flashy in its style to be great. At the center of Tokyo Story is an honest story fueled by pure emotions.

11. Seven Samurai (Dir. Kurosawa Akira, 1954)

While Ozu was focused on melancholy and honest works after WWII in Japan, Kurosawa Akira was instead interested in giving audiences pure entertainment and gave birth to the modern day action movie with the release of Seven Samurai. But sheer entertainment alone does not constitute reason enough to be placed on this list, for Seven Samurai represents grand filmmaking at a high level, and offers high-octane action scenes that make modern action movies seem dull in comparison.

The story is simple. A poor farming village recruits a group of samurai to help defend themselves after a series of incidents in which bandits have come and terrorized their homes. The film runs roughly three and a half hours long, but Kurosawa uses the first half of that time to carefully establish character and situation, so that everything is clearly understood and therefore making it easy for audiences to sympathize with the what is going on, before blasting off into non-stop off the walls action.

Seven Samurai is a good example for those interested in making action movies, as it has a basic fundamental structure to it. On top of that, it is simply an entertaining movie that almost anyone will enjoy.

12. The Searchers (Dir. John Ford, 1956)

The Western genre is cinema’s oldest genre, dating back to before cinema had even focused genres in its vaudevillian era. It was especially popular in Hollywood and gave birth to some of the most iconic actors and directors in the medium. Two such individuals are actor John Wayne and director John Ford, who together made what is perhaps the greatest Western of all time, The Searchers.

A lot of what makes The Searchers so significant and so successful is John Ford’s use of the classical Western style. Unlike a Spaghetti Western, specifically the ones directed by Sergio Leone, which featured an antihero who did his actions in the service of no one but himself and a style that consisted of quick cuts and elongated action sequences, the classical style had a true, selfless hero at the center of the story and had a directorial style that largely consisted of large wide shots, so that the audience could feel the weight of the film’s grandeur and the scope of its beautiful landscape.

While the hero of this film, Ethan Edwards (played John Wayne), is not a perfect person who always makes the right decisions, as in other classical styled Westerns such as The Man Who Shot at Liberty Valance, he ends up doing the right thing for the right reasons by the end of the film. In a way, Ethan Edwards is a parallel character to Odysseus in The Odyssey, a man who begins with good intentions before being put through obstacles, both moral and physical that causes them to question their own identities.

Above all though it is John Ford’s grand direction, which is quite unlike any other film, that makes The Searchers a must see. Rarely do shots feel this alive anymore and the scope feel this naturally large. It’s a classically styled film that is rarely seen anymore and represents American cinema at both its finest and purest!

13. Breathless (Dir. Jean-Luc Godard, 1960)

Jean-Luc Godard was a key figure in the cinema’s second major film movement, the French New Wave. The French New Wave was started by a group of cinephiles and film critics at the magazine Cashiers du Cinema who were fed up with traditional narrative structure of modern cinema. As a response, they started making films that were meant to challenge viewers and reject the status quo as to how films are made. Jean-Luc Godard was easily the most rebellious and intellectually challenging of the group.

With Breathless, Godard took the clichéd story about a guy, a girl, and a gun and turned it on itself by making a film that rejects all prior filmmaking techniques and reinvents them so as to breathe new life into cinema. Among the more obvious techniques used in the film was the innovative use of the jump cut as a means to give the feeling of spontaneity.

At the time of its release, jump cuts were viewed as crude and amateur, as they ignored the 180-degree line that was so prevalent in contemporary cinema. But Godard used that state of thought to his advantage. The film is crude in its aesthetic, but so are the central characters. The jump cut emphasizes the plasticity of the characters and the situations. When the film suddenly cuts out of nowhere, there is no reason behind it, other than to give a sense of urgency.

But it’s not just the jump cut that makes Breathless so significant and revolutionary, the general aesthetic and attitude became influential on the way Hollywood made movies from there on out. Films like Bonnie and Clyde and The French Connection owe everything to Godard. At the center of Breathless is a critique of the popular films of its time and an that begs to ask what is the point of filmmaking to begin with. For the first time in film history, a film acts as a film criticism.

14. Psycho (Dir. Alfred Hitchcock, 1960)

Alfred Hitchcock was one of the first blockbuster filmmaker, creating financially successful movie after financially successful movie and Psycho continued Hitchcock’s success financially. But unlike his other successful films, Hitchcock had no studio backing with Psycho. This was due entirely to the content of the film, which was extremely controversial at its time due to the level of violence and the discussion of decadent sexuality.

But the content of Psycho and the way it plays with these themes is what makes it so significant and interesting. Psycho came out during a very conservative era in America and one littered with censorship. As such, Alfred Hitchcock had to be extremely careful when making the film he wanted to make. Instead of making a clean happy-go-lucky film, as the censors wanted him to, Hitchcock made a film that pushed their boundary limits.

But boundary pushing is not reason alone to see Psycho. It also represents a director in top form. The way Hitchcock uses his camera and plays with mise-en-scene is simply intelligent. Perhaps most interesting about the direction is the way Hitchcock toys with his audience, suggesting the plot is going to go in one way, when in reality, it is heading in the complete opposite.

Psycho is simply a great film that everyone should see. (On a side note, there is a great book by François Truffaut in which he interviews Alfred Hitchcock that should be required reading in a film schools).

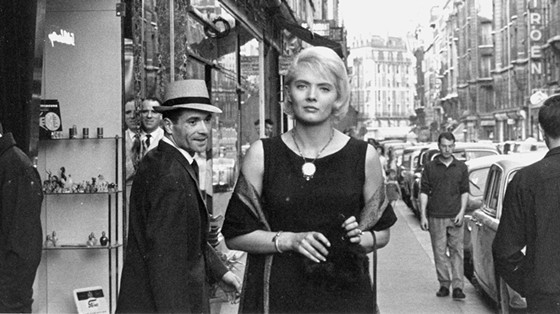

15. Cleo from 5 to 7 (Dir. Agnes Varda, 1962)

As with a lot of different mediums, in cinema women get pushed to side and are often ignored. Filmmakers like Alice Guy-Blache, Kelly Reichardt, and Claire Denis are not household names despite being influential and well received. But perhaps one of the more unsung female filmmakers is Agnes Varda, whose films emphasize character over story and are commonly told from the female perspective and about what it means to be a woman. Her second feature, and most well known film, Cleo from 5 to 7, is a prime example of Varda’s method.

Cleo from 5 to 7 has a simple premise- a young pop singer waits from 5 to 7 to hear back from her doctor to confirm whether or not she has cancer. This simplicity allows for Varda to focus almost entirely on character, as well as bring up and explores existential ideas of what it means to be alive and human, and the nature of despair and death.

Had Varda given the film more of a plot, then these ideas would not have been fully realized and the film would not have been as successful. It is a great example in less being more.

At the heart of the film is the character Cleo. Agnes Varda sets her up as doll like individual. For this reason, as well as being a pop singer, Cleo is reminiscent of the public personalities a Hollywood actress from that time, like Sandra Dee or Audrey Hepburn. She is innocent and naïve, not fully aware of the harshness of the world around her, and helpless, the view of what was seen as a good girl in 1950s media.

Throughout the course of the film, her crisis causes her to think about who she is as an individual and question whether or not her life has really been lived to its fullest. Unlike contemporary female lead characters, who get the dream man at the end or find satisfaction from an adventure, Cleo simply grows and becomes a fuller, more aware individual.

For film students, Cleo from 5 to 7 is a great example of less being more and ways that philosophy can effectively be incorporated into plot. It also is a landmark in feminist cinema, something that continues to be undervalued and under-watched.

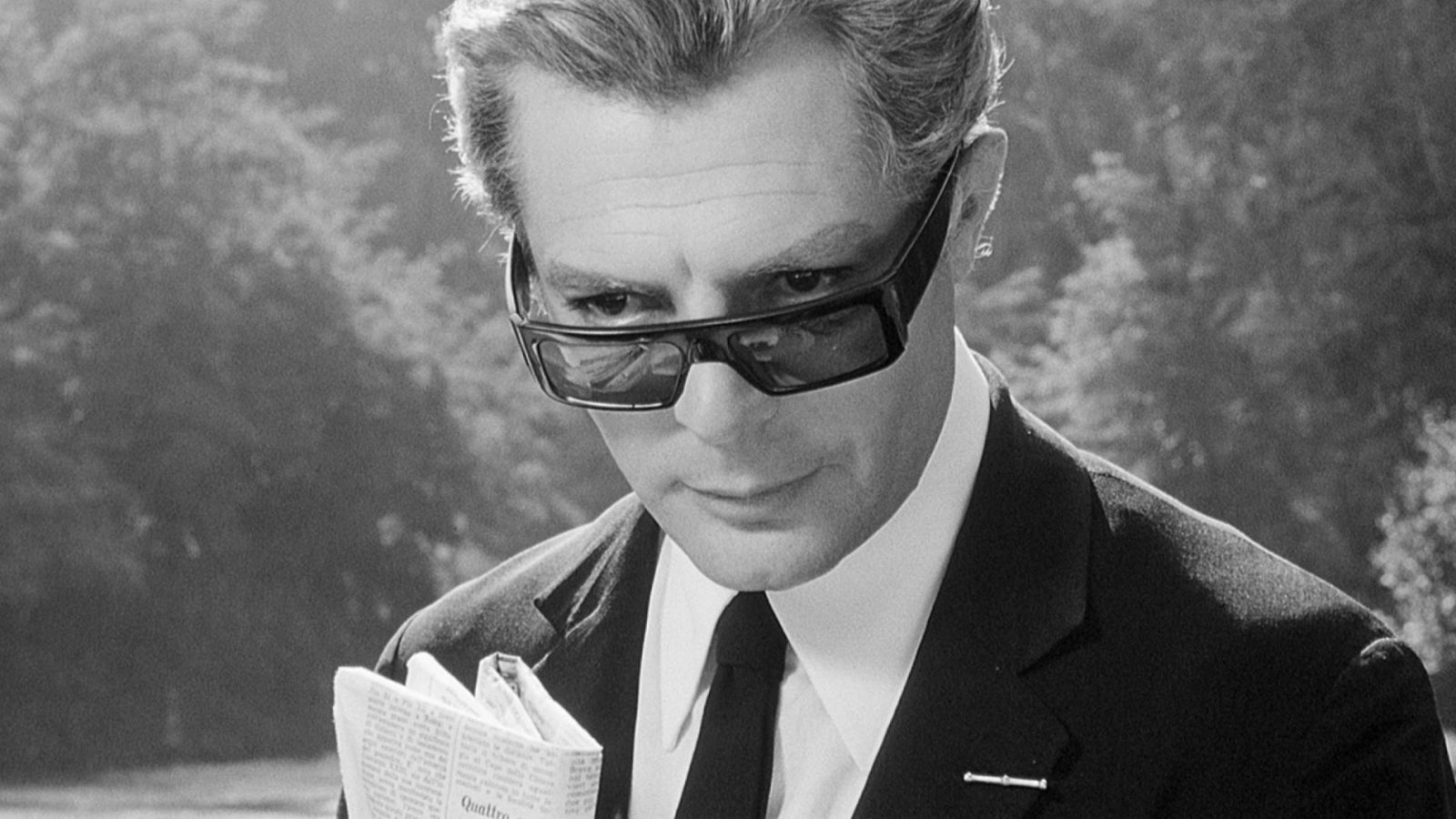

16. 8 ½ (Dir. Federico Fellini, 1963)

Making a film about the filmmaking process is one of the toughest things to do successfully. Which is why when it works, it usually is something special. Such is the case with Federico Fellini’s masterpiece, 8 ½.

8 ½ is not simply a great movie; it is one of the very best movies ever made. It is a celebration of cinema as whole, not just the filmmaking process. Cinema in the eyes Il Maestro Fellini is a grand circus that is equal parts fantasy as it is dream.

The film’s title refers to the amount of films Fellini, himself, had made up until that point. The film itself was his follow up to his internationally successful, La Dolce Vita. Knowing this information is a starting point for what the film is about, a director, played by Marcello Mastroianni (Fellini’s frequent onscreen avatar), who on the heels of his most successful film, begins to suffer from director’s block.

As a result he begins to flash back and forth between dreams, memories, fantasies, and reality. In the process, the line between fiction and reality is blurred.

8 ½ is the embodiment of Fellini, showing his passion and energy in peak form. The camera is constantly in motion, especially in scenes featuring large crowds, so as to give off a hectic and energetic sensation that resembles a circus, something Fellini held near and dear to his heart.

Nino Rota’s music further pushes this sensation, as it too sounds as if it came straight out of a circus. But the score serves a deeper purpose, as it is seemingly in perfect sync with the film, making one wonder what was conceived first- the score or the story? But does it really matter?

8 ½ is simply the best film on the subject of filmmaking and should be required viewing for anyone interested in making a professional career out of it. It is a display of an energetic filmmaker doing what he loves, and what he loves is cinema.

17. Au Hasard Balthazar (Dir. Robert Bresson, 1966)

Within this list, the subject of faith in cinema has been discussed in the case of The Passion of Jeanne d’Arc. But that is film that was made by a man who was religiously devout. In the case of Robert Bresson, who was a self described Atheist; an outsider perspective is given to the belief.

Similar to Ozu Yasujiro, Robert Bresson was a very thoughtful filmmaker who looked at situations from all perspectives and demanded his audience do the same. Resulting in a very rational style and more intelligent and thought provoking films. This is most present in his film Au Hasard Balthazar.

Au Hasard Balthazar is about the life of a donkey, beginning at his birth and ending with his death. The film follows him from owner to owner, told almost entirely from his perspective, and witnesses the interactions that each of his owners has with other individuals and the way they work with situations.

By having the film seen from the perspective of the donkey, Bresson is forcing his audience to have God’s objective perspective. This is further emphasized by the fact that the donkey never speaks back or significantly communicates with the human characters, nor does he make any facial expressions to clearly signify what he is thinking, thus symbolizing the omniscient presence.

But as stated earlier, Bresson was a self-described Atheist. As such, the film is not in immediate praise of God’s perspective and Bresson demands his audience to think about the morality of his stance, as well as the actions and feelings of his human characters. The donkey’s lack of emotion and communication is at times cold or distant, making one question whether or not he has sinister ulterior motives- a very existential question.

In Au Hasard Balthazar, Robert Bresson created a masterful film that questions the morality of god and man. It is also a great example of how one can use perspective effectively and portraying religion without being preachy or condescending. Additionally, Robert Bresson wrote a really great book on his filmmaking process, entitled Notes on Cinematography. It is hard to find, as it is currently out of print in the United States, but is really worth seeking out and should be mandatory reading for film students.