7. Vertigo (1958)

Upon its initial release it was easily the most misunderstood Hitchcock film. The traditional murder mystery thriller he was famous for (and essentially pioneered) would take an unexpected detour during this film’s second act turning point. Hitchcock reveals the mystery of the film well before it is over.

Traditionally in thrillers, the audience would find out who the killer is during the final moments of the film (the butler did it!) Instead, Hitchcock divulges the secret with 45 minutes still left! Back in 1958, audiences were disappointed with this unexpected change in direction. By knowing the mystery it is no longer escapism. However it is precisely at this moment where Hitchcock re-invents the thriller genre.

Much like what he would do two years later with Psycho, he reverses our expectations and takes us down a different path. You thought it was going to be about Madeline being possessed by Carlotta the ghost? Think again! No, instead we get a psycho-drama that examines an unhealthy and paranoid male obsession. Vertigo may very well be the greatest psychologically perverse love story in film history.

Given that Hitchcock suffered from similar obsessions as the character Scotty (James Stewart) in the film, it is easily his most personal and boldly artistic film. It is ultimately a cautionary tale: do not fall in love with a romanticized image. After all, we all have a tendency to form an idealized image of those we become infatuated with, which easily comes crashing down once the initial infatuation is over.

In many respects, it is a powerful feminist statement – don’t think of women as one-dimensional, or categorize them. “Dress like this, act like this, say exactly this.” Is it any wonder our heroine kills herself in the end? Ironically, Scotty overcomes his fear during the final moments, but by vanquishing any possibility for love. It is both a victory and a tragedy.

Vertigo is not just about the fear of heights, it’s about the fear of falling in love. The dizzying heights that love can elevate us to and then traumatically drop us. Characters continue to fall throughout the story. Four falls, four deaths. It’s the ultimate tragic love story. It also contains one of the greatest film scores in history, with Bernard Herrmann referencing Tristan & Isolde, one of opera’s most tragic love stories.

In the end, Vertigo was too much for audiences of the time to handle. James Stewart’s performance alone was hard enough to take; the ultimate every-man was playing a obsessive and unappealing character that shocked many fans. Yet, time has been kind to Vertigo. There is more interest in the film now than ever before. As a result, it has been the only film in the past 50 years to knock Citizen Kane off the top film spot in Sight & Sound’s prestigious poll. Hitchcock’s daring honesty has made it a timeless and compulsively watchable film.

8. Peeping Tom (1960)

Legendary British director Michael Powell would make many classics during the 40‘s with his producing partner Emeric Pressburger. They had already made film history as The Archers. Powell was also married to three-time Oscar winning editor Thelma Schoonmaker who happens to be Martin Scorsese’s award-winning editor. However, Peeping Tom destroyed Powell’s career.

Banned in England for 35 years, it is a psychologically disturbing character study that was far ahead of its time. Ironically, it makes a great companion piece to Hitchcock’s Psycho, released the same year. But where Hollywood embraced Hitchcock’s horror classic, Britain felt Powell’s film was too perverse and ugly. Despite its thematic “sleaziness, cinematically speaking, it is extremely sophisticated. Powell knew what he was doing and the film clearly took some big risks.

The movie opens with a POV shot that would be imitated in countless horror films like Black Christmas and Halloween. Both the male lead and female actor are riveting. It’s extremely hard to take your eyes off them (no pun intended). Also, the musical score, although startling, fits the scatterbrained quality of the protagonist.

The nature of the film revolves around an empathetic and damaged psychopath who is obsessed with filming his victims. During a time in the UK where most audiences did not know what snuff movies were, Michael Powell fearlessly explored this fascination with voyeurism, paranoia and even perhaps the dangers of film obsession. In the end, this forgotten gem is one of the first true cult classics.

9. L’Avventura (1960)

When released in the pivotal year of cinema’s transition, 1960, this Italian film was screened at Cannes and was instantly met with booing, yelling and anger. Audiences and critics found it pretentious, slow and boring. Completely incomprehensible. Two years later, Sight and Sound did their poll of the greatest films of all time, and many of those exact same critics suddenly voted it the second greatest film ever made, right behind Citizen Kane.

Simply put: we the audience needed to catch up with this challenging and profound film that clearly revolutionized cinema. Antonioni created his own film language with this masterpiece and many regard it as the first “modern” movie. L’Avventura teaches us an important lesson; be careful not to dismiss something so quickly on first viewing, like learning any new language, it takes practice to understand, but once you know what to look for, every frame is loaded with intense meaning. Eros is sick indeed.

The film is an extreme example of visual storytelling, where the mis-en-scene holds far more meaning than any of the dialogue. How are the characters standing? Are they facing each other? What’s in the background? What does the landscape look like? Every shot speaks volumes like a famous painting might. Antonioni was truly the poet of images.

To boot, Monica Vitti’s controlled performance of “interior neo-realism” was as groundbreaking in its own way as Marlon Brando’s Method Approach a few years earlier. At the time of its release, L’Avventura was simply fresher than anything else around.

10. Wake in Fright (1971)

This highly unusual Australian film from the 70’s didn’t get much recognition at the time but recently, due to a stunning restoration, it is finally getting the attention it deserves. This surreal character study follows a school teacher protagonist on an existential odyssey through the nightmarish landscape of small towns in the Australian outback.

Upon initial release many audiences found it baffling and frankly upsetting. After all, animals are killed and the characters divulge in atrocious debauchery. However, upon closer inspection, our hero’s journey is one of self-discovery and the trials of overcoming the fear of death. From Denial, Hope, Anger, Despair and Acceptance, he conquers each stage of death.

Not surprisingly, Martin Scorsese champions the film. He even pays homage to it in Casino with the bird’s-eye view of Sharon Stone throwing the dice in the air, which is a reflection of a gambling scene in Wake in Fright where the hero tosses gambling pieces in the air. There is also a subtle homosexual subtext that dances just under the surface, bringing into question whether or not our hero even has a sweetheart waiting for him back home. Is she a figment of past memories? Is she simply an excuse for a vacation when in reality he wishes to indulge in these debaucheries and very testosterone-driven activities.

Wake in Fright is a frightening film that disturbs, provokes and leaves plenty for the viewer to reflect upon. A lost 70’s classic that is only now finally getting its unique reputation and analysis that it deserves.

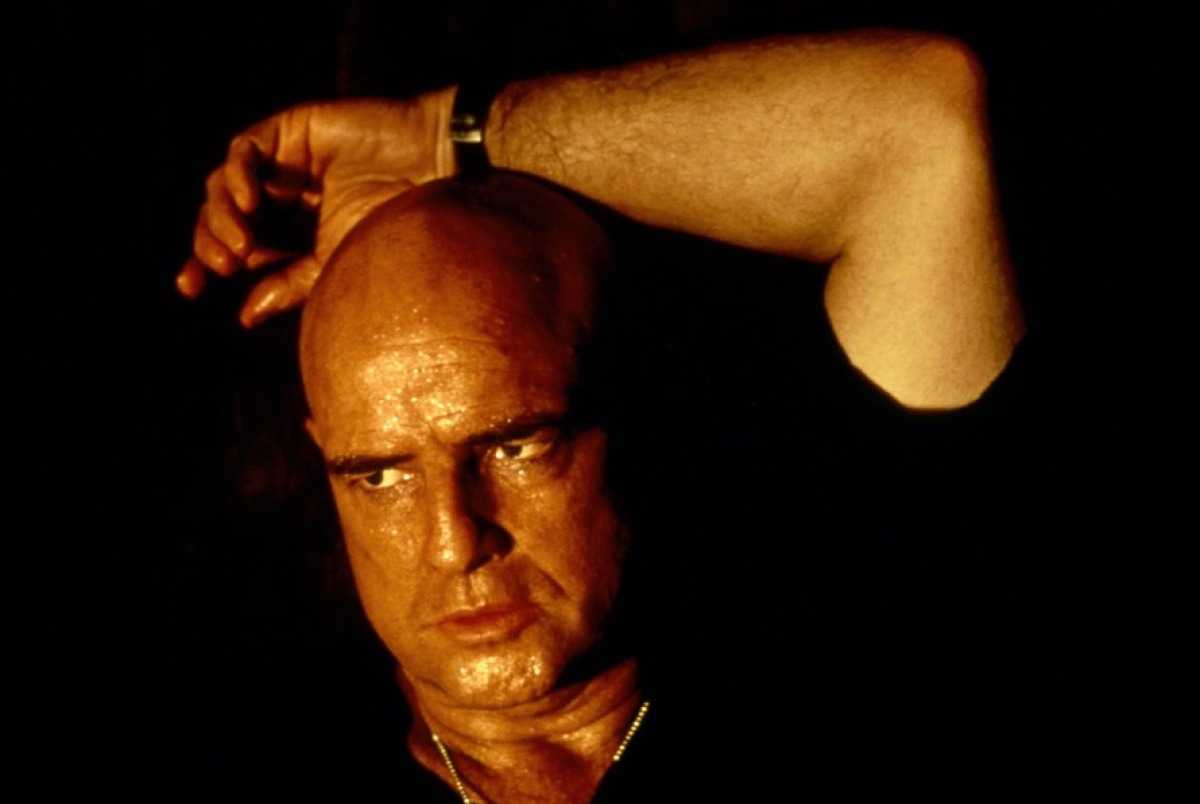

11. Apocalypse Now (1979)

Technically speaking, has there ever been a more accomplished film? From the cinematography to the editing and its incredible sound design, it is truly a cinematic experience that astonishes both sight and sound. Amidst war there is a thin line between sanity and insanity, like a snail balancing a thin razor.

As our main character journeys up the river, each stop explores a different aspect of the human soul. From traveling across Man’s tortured psyche, confronting both animal instincts and carnal desires, trying to come to terms with history and confronting denial, teetering on the thin line between the rational and the horrific, until ultimately reaching the final resting place – the heart of darkness.

Apocalypse Now was at first far too much for audiences to digest. Like 2001: A Space Odyssey, it would take a few years of simmering, reflection and catching up to. Nowadays, it’s an undisputed masterpiece. The Redux version, although controversial, enriches an already hugely complex story. It remains the finest war film ever made and has improved greatly with age. One doesn’t just watch the film, one experiences it.

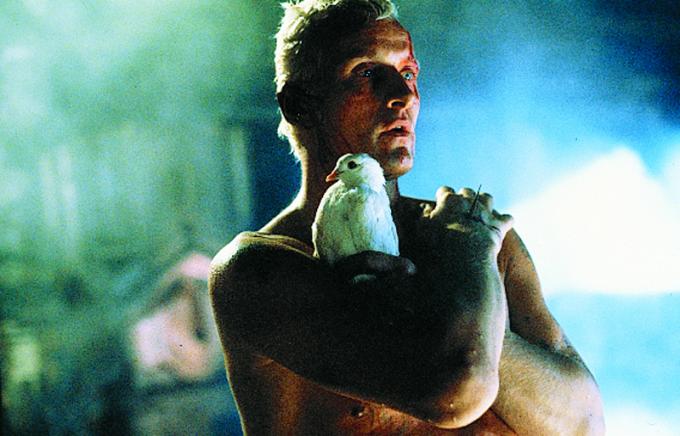

12. Blade Runner (1982)

Ridley Scott’s European sensibilities are showcased in this enthrallingly atmospheric, moody and speculative science-fiction masterpiece. Back in 1982, however, audiences’ pallets were more suited to feel-good movies like E.T., so this bleak, ambiguous and slow-paced dystopian tale was difficult for some to swallow.

However, as is the nature of all things great, Blade Runner gained a cult following which would ultimately grow exponentially with each passing year, thanks in part to pay TV and home video which helped it reach an ever-expanding audience (what cinephile can forget the glorious widescreen laserdisc release on Criterion?).

By its tenth anniversary, there was immense demand for a “director’s cut” and, most recently, Ridley Scott made fans go wild with the release of his definitive “final cut” which is indisputably the best version out there. Many call Blade Runner the most influential sci-fi film of the 80’s… arguably, even of all time. (Star Wars is its toughest competition).

The film is compulsively watchable as a cinematic experience. Its look, style and pace has since been imitated countless times in film, video games, music videos and even television commercials! Scott has proven that he clearly knows how to build worlds and environments that seep into our common unconsciousness. Be it Alien, Legend or Prometheus, many of his films capture atmosphere and ambiance better than most.

It is difficult to come up with another film that matches the sheer beauty of Blade Runner’s haunting images. The script is intelligent, affecting and fascinating in the philosophical debate that it offers – a debate more relevant today than ever before. At a time where A.I. has become cutting edge, the question of what does it mean to be human, couldn’t be more prescient. As Tyrell states, “More human than human is our motto.”

Part and parcel of what elevates Blade Runner is its hypnotizing score and terrific sound design. Both aid in enveloping the viewer and osmosing them into the visuals. Finally, replicant Roy Batty’s death soliloquy ranks as one of the most tender death scenes on screen. As if all that wasn’t enough, Scott ends the film with a hook – a question: is Rick Deckard a man or a replicant? A question passionately argued over by fans to this day.

So, it is all these aspects – atmosphere, style, score, philosophy, mystery and subtext – that pushes Blade Runner into being a film ahead of its time. So far ahead, in fact, that we are still catching up to it.

13. The Thing (1982)

After the phenomenal success of Halloween, director John Carpenter wanted to pay tribute (yet again) to his long-time idol Howard Hawks. Remaking Hawks’ production of The Thing From Another World was already a risk, but imbuing it with the goriest effects the world had ever seen was something else! The film’s bleak ending, horrific killings and all-around gloomy atmosphere didn’t gauge well at the box office, audiences wanted to see more aliens like E.T. and not something a character in the film describes as, “You’ve got to be fuckin’ kidding.”

Today, however, The Thing is widely regarded as the ultimate monster movie. Despite pioneering ground-breaking visual effects in prosthetics, Carpenter also borrows classic suspense elements that are reminiscent of Hitchcock, while its archetypal open-ending has left fans locked in debating for decades whether our hero did in fact kill the alien (or perhaps the character Chiles hiding something?).

One of the film’s big draws is the incredible visual effects created by prosthetic artist Rob Bottin. It took Bottin over a year to complete his incredible work on every creature effect, though Stan Winston assisted on transforming the Husky. Speaking of the Husky – it was the real deal. The same animal was used throughout the movie and – as the story goes – it was half wild and had an unreliable trainer who famously preferred to spend his time drinking in the corner rather than keeping an eye on it. The hound would growl and snarl at the cast and crew during filming and everyone was genuinely terrified of it.

The shoot itself was an extremely difficult one. In addition to the dangerous dog, it was freezing and it wasn’t only the husky’s trainer who was drinking – everyone was. Carpenter and Co. needed so desperately to keep warm during the filming that alcohol turned out to be the simplest solution which resulted in the all-male team quickly deteriorating to debauchery and recklessness.

Finally, the big explosion in the finale was reportedly ill-planned. The stunt crew had over-calculated the amount of dynamite needed, making the explosion much larger and far more dangerous than they had anticipated. Unable to put out the fire, it raged on and on for much too long. It is a bit of a miracle that more people were not hurt. Despite all the pitfalls and near disasters, Carpenter triumphed and managed to make one of the all-time greatest sci-fi horror films which can proudly be ranked alongside Ridley Scott’s masterpiece, “Alien”.