There are hundreds, if not thousands, of films that address the themes of anarchism—some favorably (like most the films listed here) and some unfavorably. There are, as well, dozens of respected lists of “anarchist films.”

While almost every recent list of films and anarch thought lists V for Vendetta, one version or another of the story of Sacco and Vanzetti, and (disappointingly) either The Matrix or Avatar, this list eschews such titles. Rather, these are twenty films that in their anarchic form and/or content engage in “the conscious creation of situations,” to appropriate Guy Debord.

The films raise more questions than they answer regarding leadership and decision making, hierarchies and egalitarianism, autonomy and heteronomy, equity and coercion, genre and storytelling, and intersections among race, class, ethnicity, gender, and sexuality. Such complexity, provocation, and affect make these films especially noteworthy.

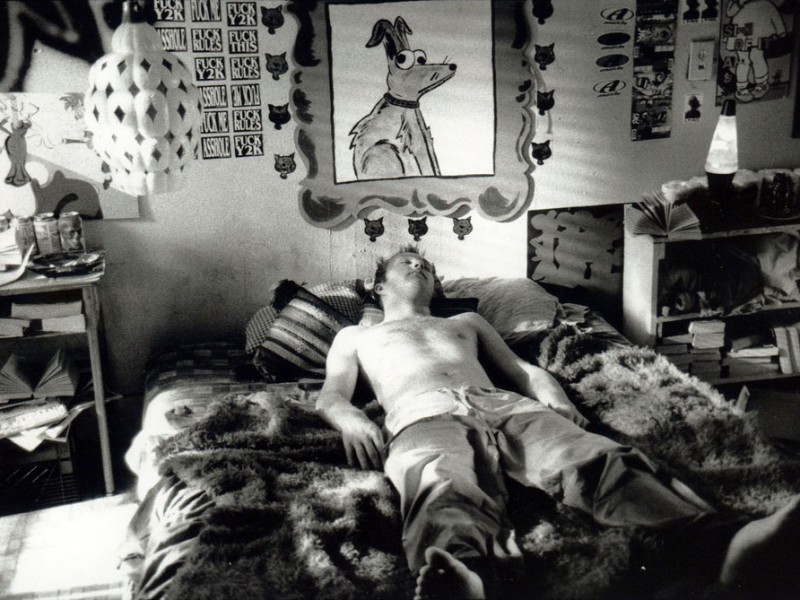

20. The Anarchist Cookbook (USA, 2002)

“We might not know what we’re for, but we know what we’re against.” Not so much an anarchist film as a hyper-individualist, chaos-driven narrative about a group of drop outs whose motto might be summed up as “Life is just a game,” The Anarchist Cookbook raises the issue of how to make films about anarchism without becoming cartoonish renderings of coercive cinema.

On the surface, this drama / romantic comedy is not about anarchist as much as it is about ill-conceived images of anarchists as counter cultural bufoons without focus.

More seriously, though, for our purposes here, a counter reading of the film calls into question mainstream images of anarchism and asks us to reconsider how the social tensions tweaked by such characters as Beavis and Butthead, Bill and Ted, and The Sweathogs might present more than meets the eye in terms of radical critiques of race, class, and social hierarchies.

19. What to Do in Case of Fire? (Germany, 2001)

Comedy about anarchism is difficult, in part, because comedy has to take its subject seriously. While What to do in Case of Fire takes on the interesting issue of what happens to young radicals years after they have settled into the system, it only half-manages to take its subject seriously enough to be comedic.

This film about former would-be revolutionaries accidentally pulled back into the fray is worth a look for the situation it describes and the few jokes it delivers. However, its reliance on sentiment and stereotype impede it developing authentic targets, such as are found in the best work of Chaplin and the Marx Brothers.

18. The Assassination of Trotsky (Italy/France/UK, 1972)

The Assassination of Trotsky was once voted one of the worst fifty films ever made, and in a 1972 New York Times review, Roger Greenspun referred to it as, “a very odd project indeed,” but one of director Joseph Losey’s which he preferred.

The film is a reenactment of the final months of Trotsky’s life beginning on May Day, 1940, in Mexico and is based on books, diaries, and journals about and by the Bolshevik-Leninist agitator and founder of the Red Army. Thus, it bears the weight of a certain history that is both heavily staged and cinematographically compelling.

17. Naked (UK, 1993)

Mike Leigh’s film is a controversial choice for this list. The rough story of Johnny (David Thewlis) escaping Manchester after he rapes a woman and is threatened by her family does not address community, direct action, or larger political movements against elite or coercive authorities. Yet, the film does provide a blunt critique of any “work ethic” and an assault on middle and working class morality.

After the opening crime, the anti-hero flees to London, where he avoids associating (let alone connecting) humanely with almost anyone and refuses to engage in work or constructive activity.

In sometimes lengthy speeches, he harangues those around him and accuses everyone of being bored and says that is the problem because he is never bored, never needs to be doing anything productive to pass the time. His special target is the women he encounters. The film remains ambiguous about the causes (political and/or social) behind Johnny’s anti-conformity and anti-humanist outlook, prompting viewers to consider him carefully.

16. The Anarchists (South Korea/China, 2000)

Directed by Yoo Young-sik and written by Lee Moo-young and Bangnidamae, The Anarchists is not as much an anarchist film as a film about the use of anarchism for nationalist aims. Set in 1920s Shanghai, the film recounts the activities of a group of young Koreans trying to destabilize Japanese control of their penninsula. Through an anti-occupation terrorist campaign, the five men hope to inspire a resurrection throughout their penninsular homeland.

The film addresses the ambivalence, violence, betrayal, and economic uncertainty that are themes in most such stories. Interestingly here, after “the anarchist” lose their financial backing, they turn to street crime and gambling.

Thus, the film raises issues about the connections between crime and terrorism not always broached in other cinematic depictions of direct political action and counter action. In its look and feel, The Anarchists deploys a mise-en-scéne similar to the one Ang Lee develops in his 2007 film about Chinese nationalist insurgency in Lust, Caution.

15. The Anarchist’s Wife (Germany/Spain/France, 2008)

Set during and after the Spanish Civil War and World War II, this film directed by Marie Noelle and Peter Sehr and written by Noelle and Ray Loriga is one of the few films addressing anarchism written, directed, and produced (Marie Noelle) by a woman.

It depicts the story of a woman and her family as they struggle to reconnect with her husband who fought against Franco’s forces, was caputured and deported to a concentration camp, and was unable to contact anyone for years.

The film is important for its engagement with personal and familial elements of anarchist and resistance warfare, for telling stories about the lives of those left behind—especially women and children. While The Anarchist’s Wife does portray its separate spheres in terms of a gendered binary—the man fights / the woman stays behind—it also takes the time to reconnect the “action” of the front to the “long-suffering” of the ones left behind the lines.

In this light, the film recalls especially Rainer Werner Fassbinder’s The Marriage of Maria Braun (1979), about a wife who is not allowed to connect with her husband until it is too late for either of them. Comparing the two films, one can begin to see a more subtle gender politics at play in both.

14. Viva Zapata! (USA, 1952)

In April, 1952 Elia Kazan was called before the House Committee on Un-American Activities to identify Communists he had associated with in the 1930s. First, Kazan refused; then, he provided the names of eight people, all of whom were already known to HUAC. Kazan said he took what he thought was the least bad option, but his actions have affected his critical reception ever since.

In February, 1952 Kazan released Viva Zapata!, starring Marlon Brando as “the Robin Hood of Mexico.” While the bio-pic lionizes Zapata, it also overtly endorses a collectivist and anarchist ideology of people’s self rule against the Libertarian and Authoritarian-Leftist models espoused by other characters in the film, ultimately portraying the leader as an instrument of the peasants.

Such ideologies will appear reversed in later Kazan films, such as On the Waterfront (1954), where individual needs are shown to supercede social necessities.

13. Behold a Pale Horse (USA, 1964)

Directed by Fred Zinnemann and starring Gregory Peck (as the anarchist bandit Manuel Artiguez), Omar Sharif (as the young priest Francisco), and Anthony Quinn (as the Francoist officer Viñolas), begins and ends in defeat and conveys a sombre, fatalist tone with regard to civil war and personal vendetta.

Thus, it recalls the overall “social realist” timbre of Zinnemanns’ films and the actors with which he worked, men who often played men obsessed with losing causes, internal struggles against injustice, and a measure of masculinist “endurance,” combining elements of American modernist novels by Hemingway or Faulkner and Italian neorealist films by DeSica.

Twenty years after the war, Artiguez is hiding in France when he hears his mother is dying in a Spanish hospital. His sworn enemy, Viñolas, sets a trap for Artiguez. However, Artiguez learns—indirectly from Francisco—that his mother has already passed away. Artiguez still confronts Viñolas’s trap at the hospital, kills a sniper and several other officers, and is killed himself. The film ends with all the bodies on gurneys in the morgue.

The film is important as a 1960s Hollywood feature about the Spanish Civil War; yet, its focus on individual men and their personal motivations as the central active agents in this story neglect larger social, political contexts.

12. Lady L (Peter Ustinov, France/Italy/UK, 1965)

Perhaps every list of political/leftist/anarchist films needs one Peter Ustinov sex comedy. This film—starring Sophia Loren, Paul Newman, and David Niven—focuses on the life and loves of the Corsican Lady Lendale (Loren), who grew up doing laundry in a brothel but later became an aristrocrat through her marriage to Lord Lendale (Niven).

While at the brothel, Lady L falls in love with Armand (Newman), the anarchist thief wanted by the police until Lord Lendale arranges a pardon—in exchange for Lady L marrying him. Now that she is 80 years old, Lady L reveals to her biographer that she never stopped loving Armand, who is the father to the heirs of the Lendale estate. In this way, the film ridicules aristocratic pomposity as well as patriarchal coercion and inheritance.

11. Rebellion in Patagonia (Argentina, 1974)

Between 1820 and 1822, in the Santa Cruz region of Argentina, a group of rural anarcho-syndicalist workers, allied with urban workers in Buenos Aires, revolted against local and transnational wool and meatpacking interests. The rebellion was brutally quelled by the Argentine cavalry, and at least 1500 workers were killed.

Most were executed by firing squad after surrendering. Director Héctor Olivera’s depiction of these events focuses on the struggles with decision making within the union and the tensions within anarchist governance. The film features several lively debates where militants and workers argue over tactics and actions.

The film provokes questions about the hierarchical relations between union members and activists, depicting how the simple solution of consensus decisions may, in fact, lead to the deaths of all involved.

Rebellion won the Silver Bear at the Berlin film festival in 1974 and was a popular success with Argentine audiences, who saw parallels in the film to the contemporary situation. After the military junta overthrew the democratically elected government of Argentina, they suppressed the film.