8. On the Silver Globe (Andrzej Zulawski, 1988)

It should be mentioned that this movie was almost destroyed due to censorship.

There are parts of the movie that were left unfinished or destroyed, causing the director, through a voice-over epilogue, to narrate certain events and end the movie at a specific point. The film feels like a mirror of the times on Earth, with the political climate represented in this movie as a religious cult, with man on another planet, exploring it, conquering it, killing themselves, and causing total chaos.

The editing is like a tornado. The camera behaves as if it’s seen through the eyes of a fish. The cinematography is cold in tone and the characters seem like ghosts. There are no special effects, but there is movie magic gathered with every shot and its composition.

7. Valerie and Her Week of Wonders (Jaromil Jires, 1970)

It might seem wrong to compare this movie to “Alice In Wonderland”, but the author of the novel or the director might have been inspired in some capacity by Lewis Carroll’s novel.

This movie works better as a fantasy horror fever dream than as a coming of age story, because the movie isn’t about the coming of age of a girl. This film is more interested in depicting the adventures of the protagonist, a young girl named Valerie, and many fantastic characters rooted on people that could exist, although recreated here in a more exaggerated way.

The visual aspect of the flick works as a gothic nightmare inside a baroque painting. The camera work seems to be an homage to early 1920’s silent movies. The use of music is exquisite and precise, and although the colors of the images represent decay and depression, there is a beauty that keeps the audience going.

6. Blind Beast (Yasuzo Masumura, 1969)

An experiment is aimed at obtaining positive results. Sometimes the results are of esoteric interests. Other times they can be useful for more than one person. Sometimes the results don’t work for anyone.

The artist is always unaware of the outside world, compulsively destroying himself from the inside. It is like wanting to be reborn in order to recreate what was wrong, to master the skills, and to know the results and begin the experimentation again. The real-life constraints are money and time.

Employing a form of voyeurism as a visual narrative, it explores the madness of blindness by the use of cinematic means, in telling the story of a blind doctor who wishes to be an artist.

The voyeurism is explored in a stream of consciousness with every shot treated like a photograph. The cutting creates the only motion in most of the film. The most relevant aspect of this film is to study the psyche of a blind man who actually enjoys being blind. Here, the camera functions as a third person’s point of view. It works as though the central character is unconsciously looking at himself.

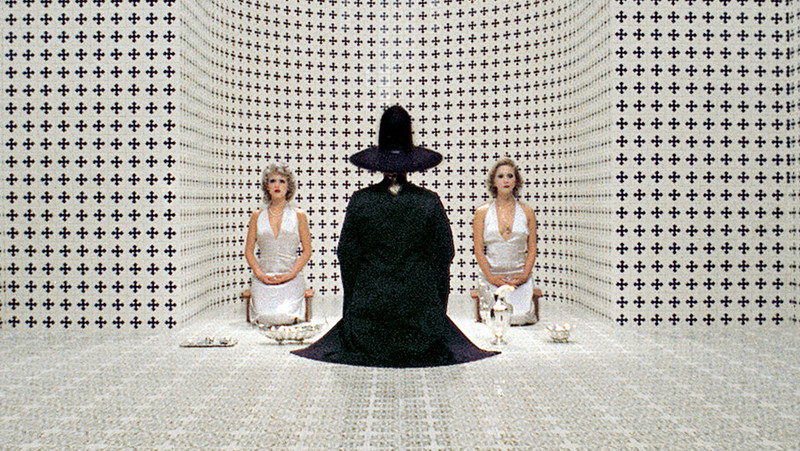

5. The Holy Mountain (Alejandro Jodorowsky, 1973)

In order to transform reality through fiction, you need to show fiction as truth. This movie is about the breaking of walls and boundaries. It is compelling and dreadful, but in a very positive way. Some despise it and that is completely understandable. It’s the form and presentation, the way that every part of the story is told, that is necessary to convey and create one language.

The first half of the movie works in a theatrical mode, while the second half is in a cinema verité style. In the end, the universal language of cinema here is used to manipulate the aesthetics of style over the substance in this film. This movie is a clear example of visual style for the sake of style, facilitating the artist taking the language of film beyond the parameters of cinematic beauty.

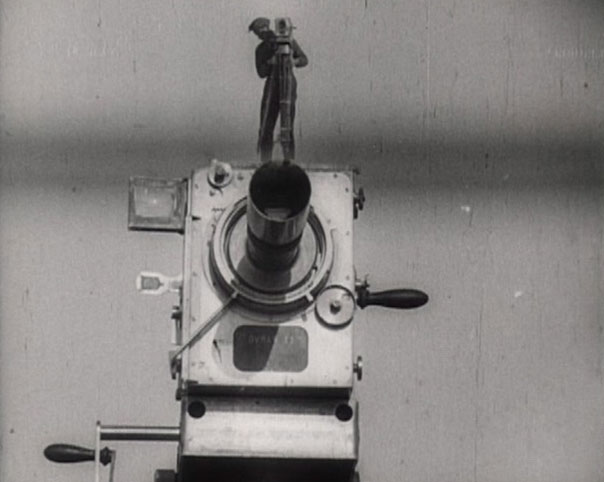

4. Man with a Movie Camera (Dziga Vertov, 1929)

This film is a great example of a film without a story, and it made history by juxtaposing unconnected scenes and imagery to create a sense of cohesion. This movie can be seen without any sound at all and it isn’t a boring experience. There is a kinetic and frenetic movement to the images and every cut made is a notable experiment.

This social cinematographic experiment is clearer than virtually any other movie ever made, precisely because of when it was shot in the late 1920s. The movements within uncut scenes and the skill of the editing is worth viewing, for a cinema student, a film buff or filmmaker. This movie is a master class and a truly inspiring experience of the early days of cinema.

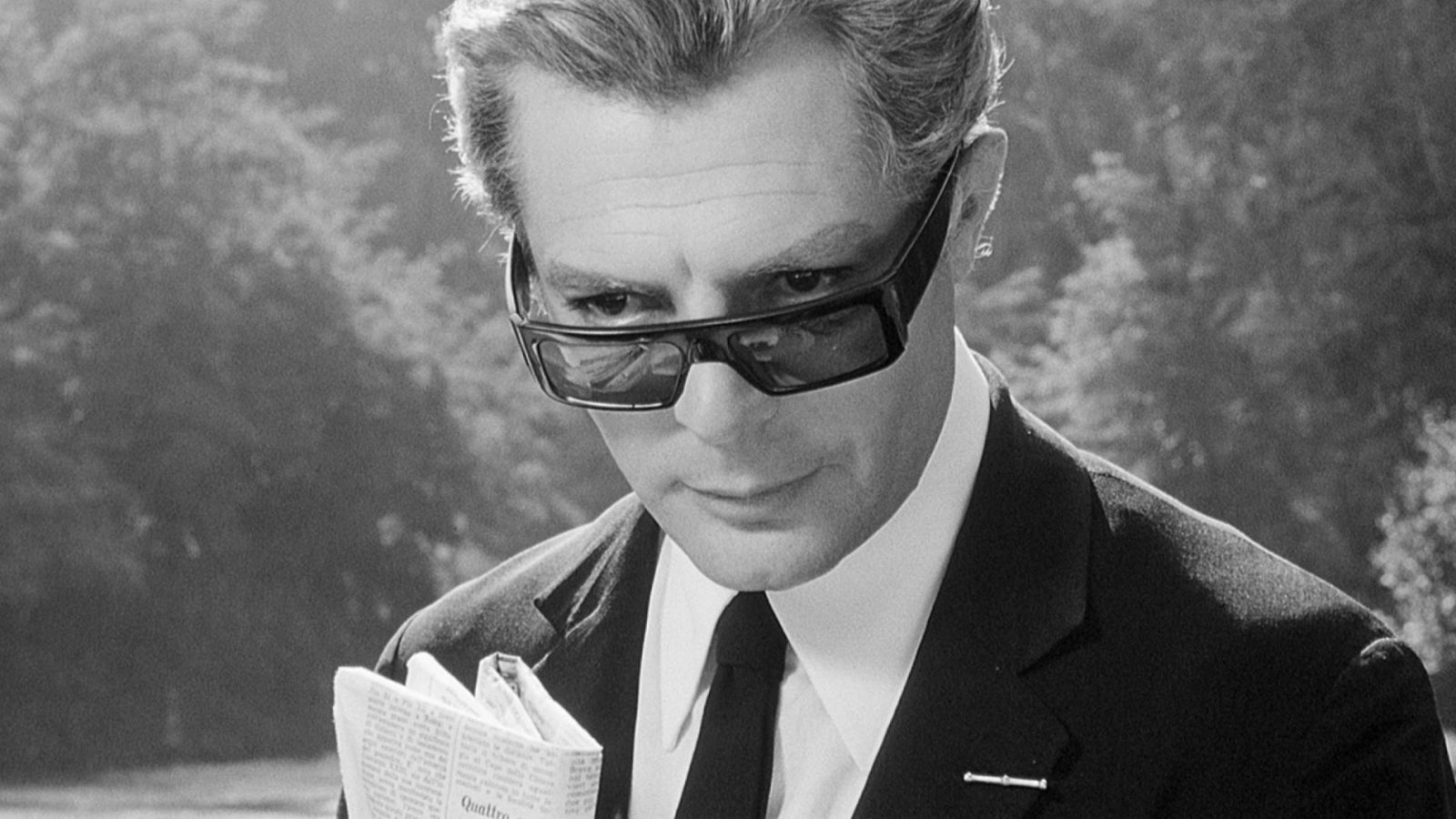

3. 8 ½ (Federico Fellini, 1969)

Dreams are dreams, and beyond that, reality is just a comedic manifestation of uncontrolled visions. This movie works as a collection of the melodramatic and the comedic, and occasionally very rough sketches. This makes it more naturalistic in working as a pastiche of dreams cut and placed together in the editing room. It’s a fantasy, but it feels so real.

This movie is frightening and funny at the same time. At times, it is like a zen master, and at other times it takes the form of a newborn baby. The cinematic language here is that of an innocent child trying to find the purest vision of what might be considered reality, while trespassing into the realm of reality.

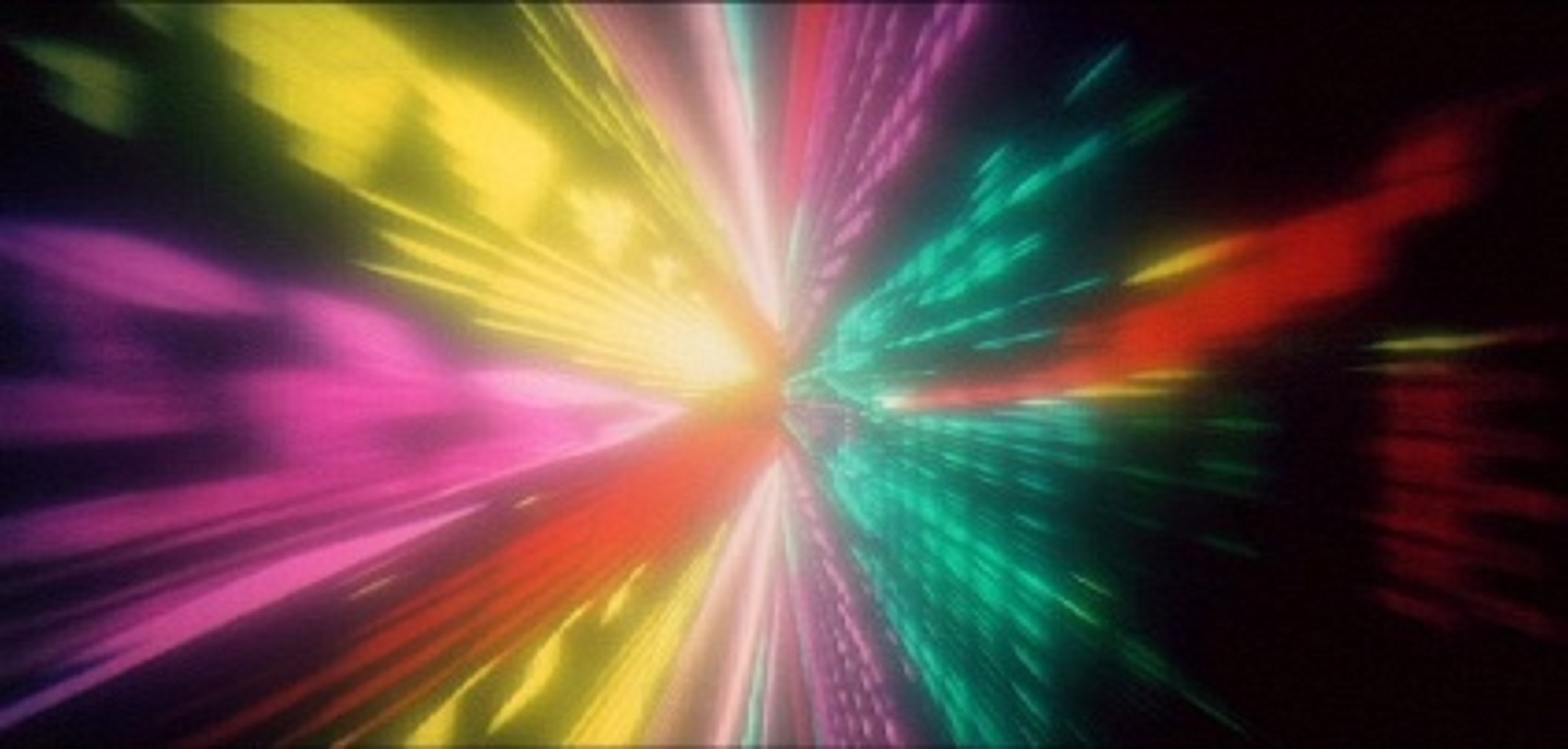

2. 2001: A Space Odyssey (Stanley Kubrick, 1968)

Death is meaningless in science. Space is an unlimited and open field waiting to be explored. Machinery and technology are part of the whole universal structure. A new world is being born as part of an always-changing universe.

Much has been said and written about this movie. Sometimes it might be hard to tell the real meaning behind this production. “2001: A Space Odyssey” is the first movie where Kubrick’s distinctive visual style became easily distinguishable by his own cinematic language.

The pacing, editing, camera movement and lighting can be seen in all subsequent Kubrick films. Traces of this particular style were there before, but “2001: A Space Odyssey” is where these elements become clearer, not only for audiences but for the director as well.

This movie is about clarity and awareness, the state of being conscious. The production values, the lighting and every camera movement and shot are simply amazing, to say the least.

The most important aspect of this movie is the use of cinematic language. It is not about telling a story but an example of an artist trying to find his own voice, while at the same time trying to create a wonderful cinematic experience.

1. Persona (Ingmar Bergman, 1966)

There are barriers like mirrors, transparent and in absolute white, with few shades of gray. There is an intimate presentation of the principal characters, both women who bear a certain resemblance to each other. Once the story begins to unfold, it is quite natural to notice the fears, desires, ambivalences and individual concerns of each character. The resemblance is a consideration manifested at some point into the movie.

The expectation of the audience and its presence isn’t about being involved. It feels like the artists are traveling to a world where darkness is white. The audience is not the subject of what the artist is thinking, although the conscious thought is not about being too self-indulgent, but in trying to go beyond certain boundaries that requires breaking the limits of the ego. Here, the path taken is heading somewhere else, a place still yet to be explored.

As with many of Ingmar Bergman’s films, there are the close-up shots of the character’s faces. Their faces are also in the background, as are houses, islands, the sea and the sky, mirrors, and light and darkness. Every cut performs as a psychological study on the inner self of the artist. The story’s pacing is aware of the limits of cinema, and it breaks the language and creates a new form in order to tell and show things.