Asian cinema is always a force to be reckoned with in the world cinema scene. Early in the 1950s, Japan and India had made internationally acclaimed films that introduced a different culture and film language to the West. Between 1960s and 1980s, filmmakers from Japan, Iran and Hong Kong were inspired to make New Wave films, which challenged the old traditions of filmmaking.

The cinema of Mainland China grew prosperous in the last 1980s and remained strong in the 1990s. In the 21st century, South Korean cinema finally saw their boost of popularity and directors from Taiwan, Thailand and Philippines showed the world a different kind of cinema, the slow cinema.

While Asian cinema is well-known mostly for samurai and horror cinema in Japan, action cinema in Hong Kong and thrillers in South Korean, their art cinema is also worth noting. Influenced by Oriental religions and philosophies, Asian art filmmakers have made their own marks in the past 50 years or so, now Asian directors like Hong SangSoo, Jia Zhangke, and Hirokazu Koreeda are regular contenders of the three biggest European film festivals.

Here are 10 masterpieces of Asian art cinema every movie buff should see.

1. Rashomon (1950, Akira Kurosawa)

Akira Kurosawa is probably the most famous Asian director ever. His period masterpiece won the Golden Lion award at the Venice Film Festival and introduced Japanese cinema to the world cinema scene.

Rashomon is not the first film to use non-linear narrative or unreliable narrator, but it’s certainly the most influential one. It is told from four perspectives by flashbacks and there is no way to tell whose statement is true, we the audience only know what the characters tell us thus no one can be the judge.

The term “the Rashomon effect”, which deals with the relativity of truth and the unreliability of memory, has been used widely in our modern lives. The most common example is in the law business, when the witnesses tell the judge different versions of what has happened at the scene of the crime.

Rashomon is more than its innovative and complex narrative. The flamboyant visual style of the film is also worth noting. It’s the first film in cinema history that shoots directly at the sun. The best sequence occurs when the moving camera follows the woodcutter and guides us “into a world where the human heart loses its way”, the camera movement is fluid, graceful and totally mesmerizing at that time.

Kurosawa made this film when he was only 40 years old, he made a dozen of masterpieces after this one, but Rashomon will always remain the greatest legacy the Japanese master has left for us.

2. Tokyo Story (1953, Yasujiro Ozu)

In the latest Sight & Sound “Greatest Films Ever Made” poll, Hitchock’s Vertigo deservedly took the top spot from Citizen Kane. What most cinephiles didn’t notice was that Japanese director Yasujiro Ozu’s timeless classic Tokyo Story ranked No.1 in the Director’s Poll, which evidenced that he is the most inspiring film director in cinema history. Modern filmmaker, such as Win Wenders, Hou Hsiao-Hsien, Aki Kaurismaki and Claire Denis, all learned a great deal from his films.

Though his contemporaries like Kurosawa and Mizoguchi made breakthroughs in the 1950s, Ozu remained unknown to the Western world. He is a late-comer in terms of popularity but his distinctive and consistent film-making style has cemented him as one of the defining figures of Asian art cinema.

He always places the camera at the eye level of a sitting person; he doesn’t like any fancy techniques; he almost never moves the camera and he makes 180 degree cuts when he shoots two people talking. He is the perfect example of “always imitated never duplicated” in cinema.

Ozu doesn’t like dramas in his films, or should we say, drama in the traditional sense. Yet Tokyo Story is “his most dramatic film” as the director himself claimed, so it serves as the perfect getaway to his long filmography. It is a film about the deconstruction of Japanese family after WWII, but its theme of aging and generational gap is universal. It’s philosophical, cynical, and extremely moving, definitely a masterpiece every self-acclaimed movie buff must see.

3. Sansho The Bailiff (1954, Kenji Mizoguchi)

Kenji Mizoguchi, along with Akira Kurosawa and Yasujiro Ozu, are often called “the big three” of Japanese cinema. His late masterpieces Ugetsu and Sansho the Bailiff both won the Silver Bear at the Venice Film Festivals in the early 1950s’. These two consecutive wins made him one of the most internationally acclaimed director in Japan at that time.

Mizoguchi is famous for his mastery of the long takes and mise-en-scene. He likes to portray woman’s place in society in period dramas (also known as jidai-geki in Japan), which made his films sad but beautiful.

Sansho The Bailiff, one of the saddest films ever made, is indeed a powerful tear-jerker. Jim Emerson from rogerebert.com described his film watching experience like this: “I don’t believe there’s ever been a greater motion picture in any language. This one sees life and memory as a creek flowing into a lake out into a river and to the sea.” This just sums up the whole film perfectly. Sansho The Bailiff is the quintessential Asian art cinema.

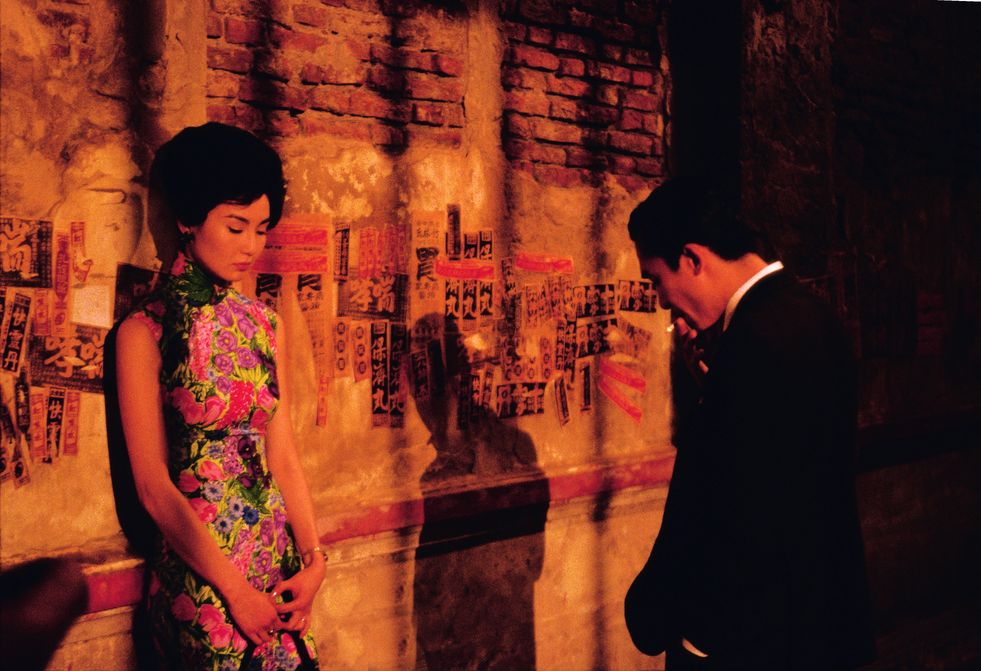

4. A Moment of Innocence (1996, Mohsen Makhmalbaf)

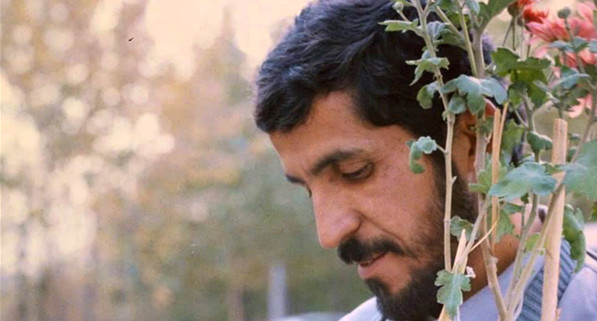

Mohsen Makhmalbaf is a rebel filmmaker and one of the most important figures in Iranian cinema. He was sentenced to death after stabbing a policeman at the age of 17 and was released in the wake of the Iranian revolution. Several of his movies were banned for their radical political statements. Because of the sensitive themes of his films, his films didn’t get distribution as wide as the works of his peer and friend Abbas Kiarostami. To some extent, his achievements were also overshadowed by Kiarostami.

Makhmalbaf’s cinema concerns the lower depths of Iranian society and that’s why he won the hearts of so many Iranian audiences. He founded the Makhmalbaf Film House in 1996 to educate film-making students. His family members became direct beneficiaries of his institute, since his wife Marziyeh Meshkini (The Day I Became a Woman) as well as his two daughters Samir (The Apple, Blackboards) and Hannah (Buddha Collapsed out of Shame) all made notable feature films under his guidance.

Makhmalbaf made A Moment of Innocence based on the policeman-stabbing incident 22 years later. It is not a documentary or a fictional film that is trying to re-stage the whole event, instead, it’s a meta-film about the making of re-staging the whole event. The director is not trying to find redemption by making this into a film. He just wants to show how difficult it is to show the history precisely in a film.

The line between real-life character and movie character is constantly blurring. Accidents occur every time you think things are settled and the shooting will go smoothly. The beautiful last still tells us that what we need is bread and flower pot (as the alternative title suggests), not guns and knifes.

5. Close-Up (1990, Abbas Kiarostami)

Legendary French filmmaker Jean-Luc Godard once said that “Cinema begins with D.W. Griffith and ends with Abbas Kiarostami”. It seems like an overstatement but Kiarostami definitely deserves such praise for his innovation in cinema language. For his entry on this list, we could have chosen his palme d’Or winning Taste of Cherry or any film from his Koker Trilogy, we finally pick Close-Up for its connection with the last entry.

In the autumn of 1989, a poor man was arrested for passing himself off as the famous Iranian filmmaker Mohsen Makhmalbaf. Kiarostami, while making another film, put the project aside and decided to make a film out of it because he believes this cinema-related incident would be a perfect chance to experiment his innovative film languages. This time, a docufiction that uses the same people from the event as the actors in the movie.

The director first convinced the judge to record the whole trial and arrange the conversations according to his script, then he reconstructed the whole incident before the trial, cut them to small scenes and mixed the two in non-linear fashion. The whole movie looks like a documentary but its dialogues and structure are deliberately set up by the director. This is not the first time this kind of method is used in cinema history, but Kiarostami did it in a completely different and refreshing way.

The film didn’t have the chance to attend big film festivals in the West, but it impressed critics and cinephiles enough to pave the way for the international success of the director’s future works. It marked the international arrival of the post-revolutionary Iranian cinema and was voted as the best Iranian film ever made by the Film International magazine.