10. Tirez sur le pianiste (Dir. François Truffaut, 1960) – New Wave

Charlie (Charles Aznavour) is a floundering pianist who is trying to escape his past life. With a new potential relationship, as well as brothers being chased by gangsters, Charlie gets dragged back into the past that he tried so hard to forget.

Truffaut’s second feature is one of his most playful, more akin to Breathless and Monty Python than The 400 Blows. Truffaut’s narrative and spatial experimentations are best summed up by one scene: a gangster swears that if he is lying, his mother will drop dead, immediately followed by the image of a woman falling to the ground.

9. L’Année dernière à Marienbad (Dir. Alain Resnais, 1961) – Left Bank

X (Giorgio Albertazzi) meets A (Delphine Seyrig) at a hotel. He tells her that the two met last year at Marienbad, but A insists that this did not happen. As X recounts his story, the temporal lines collapse the past, present, and future into one diegetic world, while the spatial boundaries crumble when the hotel begins changing.

L’Année dernière à Marienbad (Last Year at Marienbad) is a brilliant collaboration between the Noveau Roman writer Alain Robbe-Grillet (who was nominated for an Academy Award for his screenplay) and Alain Resnais. Called both “pretentious rubbish” and a “masterpiece” by opposing critics, Marienbad is a complex examination of the ways in which we attempt to narrate memories, and how those memories can inform our present state.

8. La jetée (Dir. Chris Marker, 1962) – Left Bank

La jetée (The Jetty) is a complex cinematic experience wrapped in a short runtime. It is a 28-minute film composed of still images (and one moving image) of a post-WWIII dystopia. It follows one man (Davos Hanich) whose time traveling abilities do nothing to save the past from the impending war.

A landmark short film and a brilliant exacerbation of cinematic limitations, Marker’s innovations and experimentation informed his later playfulness with digital media, documentaries, and narrative trajectories.

7. Jules et Jim (Dir. François Truffaut, 1962) – New Wave

An infamous filmic ménage-à-trois, Jules et Jim (Jules and Jim) follows two friends, Jules (Oskar Werner) and Jim (Henri Serre), whose romantic entanglements with Catherine (Jeanne Moreau) become their undoing.

Playing with filmic references and employing a host of cinematic techniques, Jules and Jim stands as one of the most influential New Wave films, creating yet another iconic role for Jeanne Moreau and another masterpiece for Truffaut.

6. Pierrot le fou (Dir. Jean-Luc Godard, 1965) – New Wave

Pierrot le fou (Crazy Pete) is one of Godard’s most playful nihilist fantasies, creating a hectic and haphazard world for two quarreling lovers on the run. Ferdinand (Jean-Paul Belmondo), bored with his bourgeois life, runs away with Marianne (Anna Karina), his former lover and the babysitter of his children. The two embark on a strange journey involving terrorist plots, Americans, Samuel Fuller, and a host of random animals.

Pierrot le fou marks a high point for Godard, who was able to find an equal balance between his political themes and his experimental tendencies. He created an enjoyable film that allows the audience to take pleasure in even the most explosive moments.

5. Le mépris (Dir. Jean-Luc Godard, 1963) – New Wave

Godard’s torrid love affair with film is best represented with Le mépris (Contempt). Boasting a brutally honest performance by Brigitte Bardot (who is partially nude for a large majority of the film), it follows the destruction of a marriage between Paul (Michel Piccoli), a screenwriter working on Fritz Lang’s adaptation of The Odyssey, and Camille (Brigitte Bardot), a former typist who has suddenly started hating her husband.

Godard’s Technicolor dream of beautiful Italian villas, fragmented storytelling, and playfulness with diegetic sounds, is one of Godard’s many 60s masterpieces, culminating with a scene of Godard assisting Lang in filming a sequence from The Odyssey.

4. Hiroshima, mon amour (Dir. Alain Resnais, 1959) – Left Bank

Written by Marguerite Duras (who was nominated for an Academy Award) and directed by the magnificent Alain Resnais, Hiroshima, mon amour (Hiroshima, My Love) set up the career for a remarkable director who was obsessed with exploring the effects of memory. Two unnamed characters, a French actress (Emmanuelle Riva) and a Japanese doctor (Eiji Okada), have a brief love affair that leads to memories of their respective pasts, which relate tangentially to the effects of the bombing of Hiroshima.

Experimental and haunting, lyrical yet abstract, Resnais created his first feature masterpiece about the tragedy of relating the past to one’s present state.

3. Cléo de 5 à 7 (Dir. Agnès Varda, 1962) – Left Bank

A staple of feminist filmmaking, Agnès Varda’s brilliant Cléo de 5 à 7 (Cléo from 5 to 7) is a story about a woman walking toward death and embracing the unknown.

Cléo (Corinne Marchand) is a pop star who is awaiting the result of her medical exam, fearing she may have stomach cancer. During her trip to the hospital, Cléo sheds her superficial exterior (wearing plain clothes instead of gaudy robes, and showing her real hair instead of wearing a wig). It is a real-time investigation of a woman stripped bare in the face of the unknown, utilizing some of the most remarkable techniques and sequences ever.

2. Les 400 coups (Dir. François Truffaut, 1959) – New Wave

Truffaut’s semi-autobiographical Les 400 coups (The 400 Blows) is a quintessential New Wave film because it was the entry point for many (including yours truly) into the New Wave. Employing a multitude of techniques, including mise-en-scène, voice-over narration, and filmic references, Truffaut creates Antoine Doinel – one of the most notable icons of the New Wave and of French history – a young boy who deals with the injustice of his illegitimacy and the oppression of juvenile detention.

The film famously ends on an ambiguous note, with a freeze frame of Doinel running toward an unknown future and staring directly into the camera.

1. A bout de souffle (Dir. Jean-Luc Godard, 1960) – New Wave

There was before Breathless and after Breathless… Many Truffaut enthusiasts may argue against my placement of A bout de souffle (Breathless) at the top of the list, but there is no denying Godard’s impact on New Wave films (both inside and outside of France) and on cinema in general.

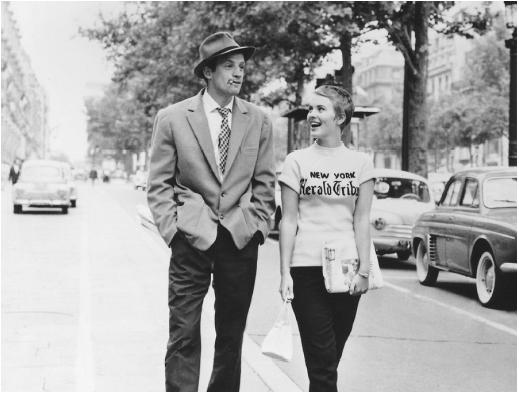

The story of the charming gangster, Michel (Jean-Paul Belmondo), running away from the police while wooing his American girlfriend, Patricia (Jean Seberg), brought self-reflexive attention through its playfulness with jump cuts and its rolodex of film references. Its iconic characters and suave actors became legends with a simple brush of the thumb across the lips and the exclamation of “New York Herald Tribune!”

Author Bio: Jose Gallegos is an aspiring filmmaker with a B.A. in Film Production/French from USC and an M.A. in Cinema, Media Studies from UCLA. His main interests are the French New Wave, Left Bank Cinema, and Spanish Cinema under Franco. You can read his film reviews at nextprojection.com and view his film poster collections at discreetcharmsandobscureobjects.blogspot.com.