7. Je, tu, il, elle (Dir. Chantal Akerman, 1974)

Before Jeanne Dielman, there was Je, tu, il, elle, a portrait of a woman (Chantal Akerman), or rather an aimless narrative that paints the woman in various settings (a locked room, a café, a truck, and her girlfriend’s house) and situations (eating only powdered sugar, fellating a truck driver, and having sex with her girlfriend).

The film’s slow pace and lack of editing feel like a rehearsal for her later masterpiece, and the use of long takes helps to create an image of an unobjectified woman participating in unfetishized sex scenes.

6. Thelma & Louise (Dir. Ridley Scott, 1991)

Thelma and Louise is a film about two women, Thelma (Geena Davis) and Louise (Susan Sarandon) who are on the run from the law after Louise kills the man who attempted to rape Thelma. Much like Persona, the film chronicles the women’s shifting identities as they defy social boundaries and live outside of the law.

The pinnacle moment of the film is the end in which the two women, who have been chased down by the police, can either surrender or drive off a cliff. Thelma and Louise drive off the cliff, choosing to die on their own terms rather than returning to an oppressive/patriarchal society.

5. Sans toit ni loi (Dir. Agnès Varda, 1985)

One of Varda’s most successful films, Sans toit ni loi (Vagabond) is a docudrama that attempts to construct the life of an elusive drifter named Mona (Sandrine Bonnaire), who freezes to death in an empty field.

The film interviews of a slew of characters, who met and interacted (to some capacity) with Mona. Varda constructs a portrait of a woman who is walking toward her death, stripped bare of all her commodities and facing the unknown with no armor to protect her.

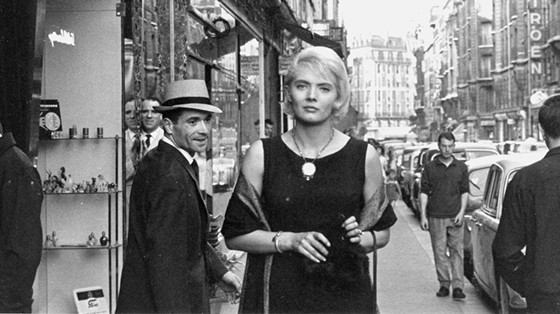

4. Cléo de 5 à 7 (Dir. Agnès Varda, 1962)

A pop singer, Cléo (Corinne Marchand), wanders through the streets of Paris while awaiting her medical results. Fearing that she has stomach cancer, Cléo endures the wait by passing time with close friends and new acquaintances.

Like the previous entry on this list, Cléo de 5 à 7 (Cléo from 5 to 7) is Varda’s portrait of a woman stripped bare in front of an unknown future, facing death without her fake hair and ruffled feathers.

Years later, Madonna approached Varda in order to remake the film, but Varda felt that Madonna’s remake would lose the feminist appeal and meaning of the film (Varda stated that Madonna could play the capricious Cléo, but that she wasn’t ready to tackle Cléo’s serious side). It is an examination of a woman who evolves and matures in order to confront her own mortality.

3. The Piano (Dir. Jane Campion, 1993)

Sold into a marriage with a New Zealand frontiersman, Ada (Holly Hunter, in her Oscar-winning role) is accompanied by two companions: her young daughter, Flora (Anna Paquin, who also won an Oscar for her role), and a piano. Ada’s marriage is marked by her infidelity and she explores her sexuality with another man named George Baines (Harvey Keitel), who has integrated himself into the Maori culture.

Jane Campion’s The Piano is a masterpiece in all senses of the word. It is a visual and tactile film that explores the sensuality of one woman’s sexuality. Elements, such as Ada’s mute voice, the juxtaposition of period piece costumes against the forest/beach, and the sensual images of Ada’s relationship to her piano, help to create a feminist masterpiece about female desire and sexual awakening.

2. Sedmikrásky (Dir. Vera Chytilová, 1966)

Two women named Marie (Jitka Cerhová and Ivana Karbanová) decide that they are done acting like good girls and instead want to be as corrupt as society.

Employing a multitude of formalist experimentations, including changing film stock and destroying any coherent narrative trajectory, Chytilová constructs a dangerous feminist masterpiece that proved too subversive for the Czech government (the film would be banned for its wasteful depiction of food).

It is a film about defying social and narrative expectations, allowing a female director to play with film form and film content. The final sequence goes as far as having the two Maries destroy a banquet, only to be punished, forced to clean their mess, and killed by a falling chandelier. Transgressive and bubbly, Sedmikrásky (Daisies) is an entertaining film that constructs brilliant moments of pleasure (and displeasure), aided by its colorful characters.

1. Jeanne Dielman, 23 quai du Commerce, 1080 Bruxelles (Dir. Chantal Akerman, 1975)

Akerman examines the routine of Jeanne Dielman (Delphine Seyrig), a mother who cooks, cleans, and prostitutes herself in order to make a living for her and her son. Over the course of three days, Jeanne’s robotic routine slowly deteriorates, leading to all out chaos with one of her johns.

It is a film that relies on cinematic limitations: it limits your perspective by its lack of editing and lack of camera movement. The film uses its three and a half hour runtime to carefully construct and habituate the viewers to Jeanne’s routine, only to break it down on the second and third day (you wouldn’t believe how many audible gasps I heard when Jeanne forgot to put a lid on a jar, or when she forgot to button a button).

Akerman constructs a tragedy out of the mundane and creates a portrait of a woman who can neither be fetishized nor objectified. It is a bittersweet love letter to Akerman’s own mother, whose postwar anxiety is reflected in Akerman’s filmography.

Recommended List:

The Craft (Dir. Andrew Fleming, 1996), Set It Off (Dir. F. Gary Gray, 1996), Imitation of Life (Dir. Douglas Sirk, 1959), The Legend of Billie Jean (Dir. Matthew Robbins, 1985), Desperately Seeking Susan (Dir. Susan Seidelman, 1985), 9 to 5 (Dir. Colin Higgins, 1980), Sweetie (Dir. Jane Campion, 1989), I Shot Andy Warhol (Dir. Mary Harron, 1996), Clueless (Dir. Amy Heckerling, 1995), [Safe] (Dir. Todd Haynes, 1995), The Descent (Dir. Neil Marshall, 2005), Heathers (Dir. Michael Lehmann, 1988), Aliens (Dir. James Cameron, 1986), All About Eve (Dir. Joseph L. Mankiewicz, 1950), Angst vor der Angst (Dir. Rainer Werner Fassbinder, 1975), 3 Women (Dir. Robert Altman, 1977), Jackie Brown (Dir. Quentin Tarantino, 1997), La mujer sin cabeza (Dir. Lucrecia Martel, 2008), Céline et Julie vont en bateau (Dir. Jacques Rivette, 1974), Raise the Red Lantern (Dir. Zhang Yimou, 1991), A League of Their Own (Dir. Penny Marshall, 1992)

Special thanks to Christopher McQuain, Michael Smith, Ben Sher, George Edwards, and Ryan Clark who have provided me with some great suggestions.

Author Bio: Jose Gallegos is an aspiring filmmaker with a B.A. in Film Production/French from USC and an M.A. in Cinema, Media Studies from UCLA. His main interests are the French New Wave, Left Bank Cinema, and Spanish Cinema under Franco. You can read his film reviews at nextprojection.com and view his film poster collections at discreetcharmsandobscureobjects.blogspot.com.