5. The Woman In The Window (1944)

With a similar cast and plot to Scarlett Street, this film-noir seems like a slightly older sibling to its successor. Again, Lang deals with what can go wrong when a man begins to think of how different his life can be, and takes a chance on a beautiful stranger.

Edward G. Robinson, plays professor Richard Wanley, who falls for Joan Bennett’s Alice Reed, a woman Richard and his friends admire based on her picture in a storefront window. Richard’s wife and children are away on a vacation, and he and a few colleagues enjoy a few drinks together. His friends leave, and when Richard himself steps outside on his way home he stops to admire the painting of Ms. Reed again.

Suddenly, there she is. He reluctantly (at first) has a few drinks with the woman, excited to recount to his friends just who he met the night before, when her supposed lover walks in. Angrily, the man tries to strangle Richard, who is forced to kill him with a pair of scissors. The two decide to cover up the murder, and when one of his colleagues gets on the case Richard himself is a witness to the police procedural taking place in front of his eyes.

The final plot twist is something is a bit abrupt and disappointing, and seems like a cop-out on Lang’s part. But rarely will you find a film so tense, so anxious (Lang had recently fled Nazi Germany, after all) as Scarlet Street.

4. Scarlet Street (1945)

In this bleak film noir, originally starring a trusting Edward G. Robinson, Lang tells the tale of cashier Chris Cross, bored with life after 25 years as a cashier for a clothing retailer, who becomes the target of deception of Kitty (a wiley Joan Bennett), who along with her thug boyfriend Johnny extort money from the enamored Chris. Chris “saves” the sexy Kitty from being attacked one night in the street (by Johnny), and over a cup of coffee Chris discusses art, leading Kitty to believe he is an artist of some renown- and has a fortune.

When they learn that Chris is a married man, the crooked couple decide to have Kitty lead him into a relationship to extort money from him- Chris begins stealing from his employer to fund an apartment, among other things, for Kitty. When Johnny tries to sell a painting done by Chris, it attracts an art critic into representing the artist, who Johnny says is “Katherine March” (Kitty). Chris’ wife sees one of Katherine March’s paintings in a gallery window, and accuses Chris of copying her work, and when he confronts Kitty she explains she sold some of his paintings because she “needed the money”.

Chris ends up murdering Kitty when he realizes she and Johnny played a huge trick on him, and eventually loses his job when his thefts are discovered by his employer (who figures he must have done it for a woman). The murder of Kitty is pinned on Johnny, and the thought of the couple being together in death drives Chris mad. We’re left with the image of Chris living out a personal Hell of guilt and shame.

This is quintessential noir, originally censored film is as dark as it is engrossing, and is a must-see for not only fans of Lang but of the film-noir genre.

3. The Big Heat (1953)

One of the best film noirs of all time, this film revolves around hard-boiled Detective Bannion, played by Glenn Ford, a “good cop in a bad town”. He’s the kind of cop that hates crime, to the point of being reckless. He has a dark interior, the side of himself he tries to hide from his family, but when his wife is murdered by an apparent car bomb, he decides to take on revenge against a local gang (which includes Lee Marvin).

Bannion’s formula of “justice at any cost” does cost people their lives, without him realizing that he may be to blame. This bipolar aspect of his crime fighting has bled into his personal life. The film can even be seen as a meditation that one cannot escape their work, and one must be mindful of the darkness they may be bringing to others inadvertently. In this, Bannion even appears to be a coward (at one point in the film, he has an elderly clerk at a junkyard knock on a suspected killer’s door to confirm his presence. He’s an anti-hero, alright.

The best film noir make it hard for the audience to tell, based on the personalities and motives of the characters, to tell just who the “good” and “bad” guy is in the story. Bannion endangers the lives of women in this film to justify his hatred and subsequent revenge on the gang in the film, and one is reminded of crooked cops everywhere, beating protesters or shooting innocents or planting drugs. Sure, Bannion holds the badge, but is he really protecting anything other than his own interest of revenge and hatred?

The Big Heat is essential viewing for fans of film noir, police procedurals, or film in general. A must see.

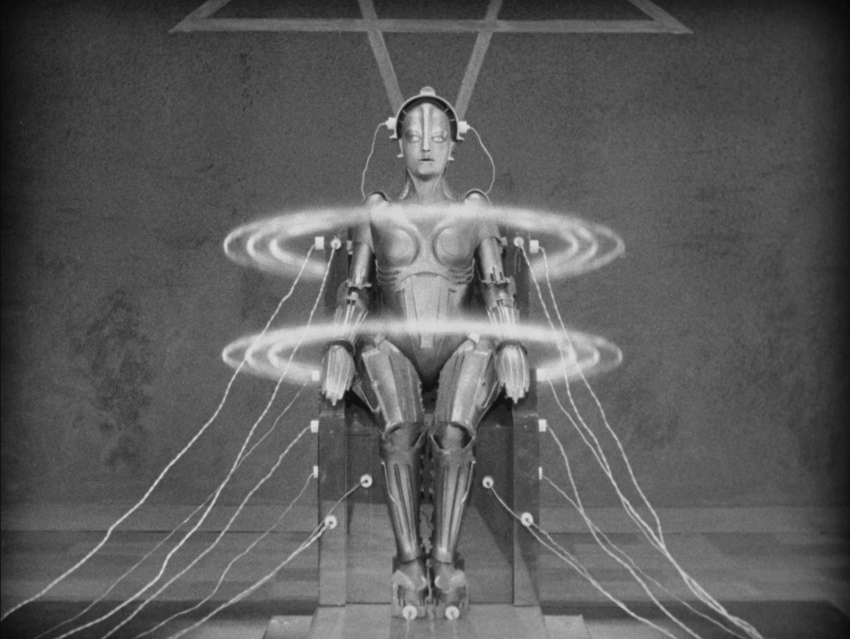

2. Metropolis (1927)

This is Lang’s epic, expressionist science-fiction piece that spawned almost everything that came after it in the genre: Star Wars (the robot C-3P0 and others in the film), Blade Runner (the jagged cityscape), Terry Gilliam’s Brazil, “Steampunk” culture and countless others certainly were influenced by the style and sheer scope of Metropolis.

Set in 2026 in the high-tech city of Metropolis, the film follows the story of Freder, whose father, Johann Fredersen, is the overlord. Freder meets Maria, a member of the class of people working below the city’s surface who becomes a social activist. When Johann learns of Maria, he instructs Rotwang, a proto-type for the “mad scientist” of films that came later, to create a robot version of Maria- to influence those who were under the spell of Maria’s ideals. Mass hysteria eventually ensues when Fredersen and Rotwang’s plan goes awry, and the robot version of Maria is burned at the stake. The film’s underlying theme deals with having compassion for fellow man, and the bridge between the mind (those orchestrating Metropolis) and the hand (the city’s workers below the surface) is the heart.

Metropolis was epic in its production- it took 310 days to shoot, cost nearly a million dollars to make, and used 30,000 extras- don’t forget, CGI wasn’t invented and large crowds of people couldn’t be put into a scene with the power of computers. While Lang, later in life, called the story “silly”, Metropolis remains one of the most influential films of all time and, is well worth the 2 ½ hour runtime (depending on which version you find, the 2002 DVD only runs 118 minutes).

1. M (1931)

Fritz Lang’s 1931 thriller, and first film utilizing sound, is often credited as the first appearance of two sub-genres in film: the police procedural and the serial killer film. It is also the film that Lang considers best in his canon. It features German stars Otto Wernicke at Inspector Karl Lohman and a 26 year-old Peter Lorre as child-murderer Hans Beckert (in the role that would typecast him for a number of years as a villain; he was considered a comedic actor before M).

The film is a haunting meditation at the sickness of society, and in hindsight may be a look at German society at the time. The characters in the film are in a state of anxiety- the police and detectives who are in charge of finding the killer, the parents in the city who are living in fear their child may not return home, and the underworld- the pimps who can’t sell sex because “there are more police than girls” on the streets. Everyone involved has reason for this killer to be apprehended.

The film’s final scene is a powerful speech by the killer. Surrounded by the city’s underworld, who decide to start a parallel search with the police, and impose their own vigilante justice, he turns the accusing finger around. “What do you know about it? Who are you anyway? Who are you? Criminals? Are you proud of yourselves? Proud of breaking safes or cheating at cards? Things you could just as well keep your fingers off.

You wouldn’t need to do all that if you’d learn a proper trade or if you’d work. If you weren’t a bunch of lazy bastards. But I… I can’t help myself!” We aren’t made to sympathize with Beckert, necessarily, but Lang treats this scene with empathy towards the killer. He forces us to reassess our firsthand perspective towards each group in the film. M is essential viewing for anyone interested in psychological thrillers or the crime genre.

Author Bio: Sam Perduta is a reference librarian at the public library in the city of New Haven, CT, as well as a touring musician and singer-songwriter in the garage-folk band Elison Jackson. He studied filmmaking briefly at the University of Southern California, and contributed to developing a Cinema Studies minor at Central Connecticut State University. His interests other than film include Pataphysics, vinyl and book hoarding, and travel (by automobile).