To consider a film “foreign” is to take part in an anglo-centered Copernican revolution, something pretty artificial for an art that was born in France and perfected by great cinematic schools from many continents.

However, we stick to this definition for conventional reasons, and maybe for a good old-fashioned imperialist fascination with the dynamics of power and language. “Foreign” as a descriptor also means intellectual, elegant, and in many cases, aesthetically superior cinema. Here are 10 of those aesthetically superior works.

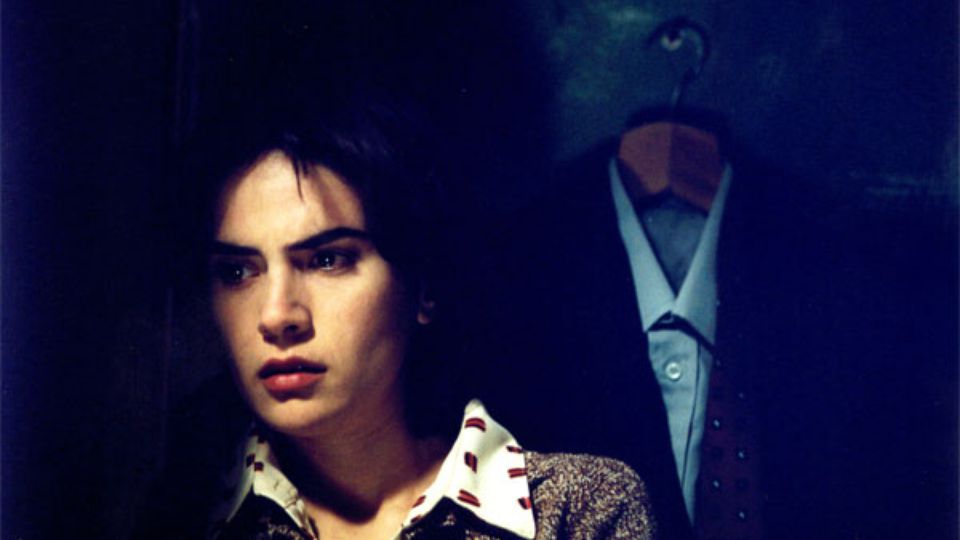

1. Good Morning, Night – Marco Bellocchio

Pink Floyd, anarchism, terrorism, the last gasps of rebellion before the decline of liberal democracies in the West, and the dominion of big business. It was a period of intense and violent political activities. “Good Morning Night” tells the story of the assassination of Aldo Moro, one of the most infamous political assassinations in the past century.

It tells the story in a psychologically nuanced way, a dark Kammerspiel in which the conversations between the terrorists and Moro explore the contradictions of the period, the eternal struggle between revolutionary and reactionary forces, but also the power of political extremism, corruption, and the role of the media.

Marco Bellocchio is one of the Italian filmmakers who embraced the more political side of the French New Wave, creating a more narrative and less ironic version of the cinema of Godard. The film is worth noting for the performances, and the political relevance (even today, the radical left remains an ambiguous force in society, between a force for liberation and authoritarian and fanatic tendencies).

What is a terrorist, who is the terrorist, who is the oppressor? The radical ideologue who takes lives in the name of his revolution, or the forces of the ruling class who oppress the workers and are inherently corrupt and insincere?

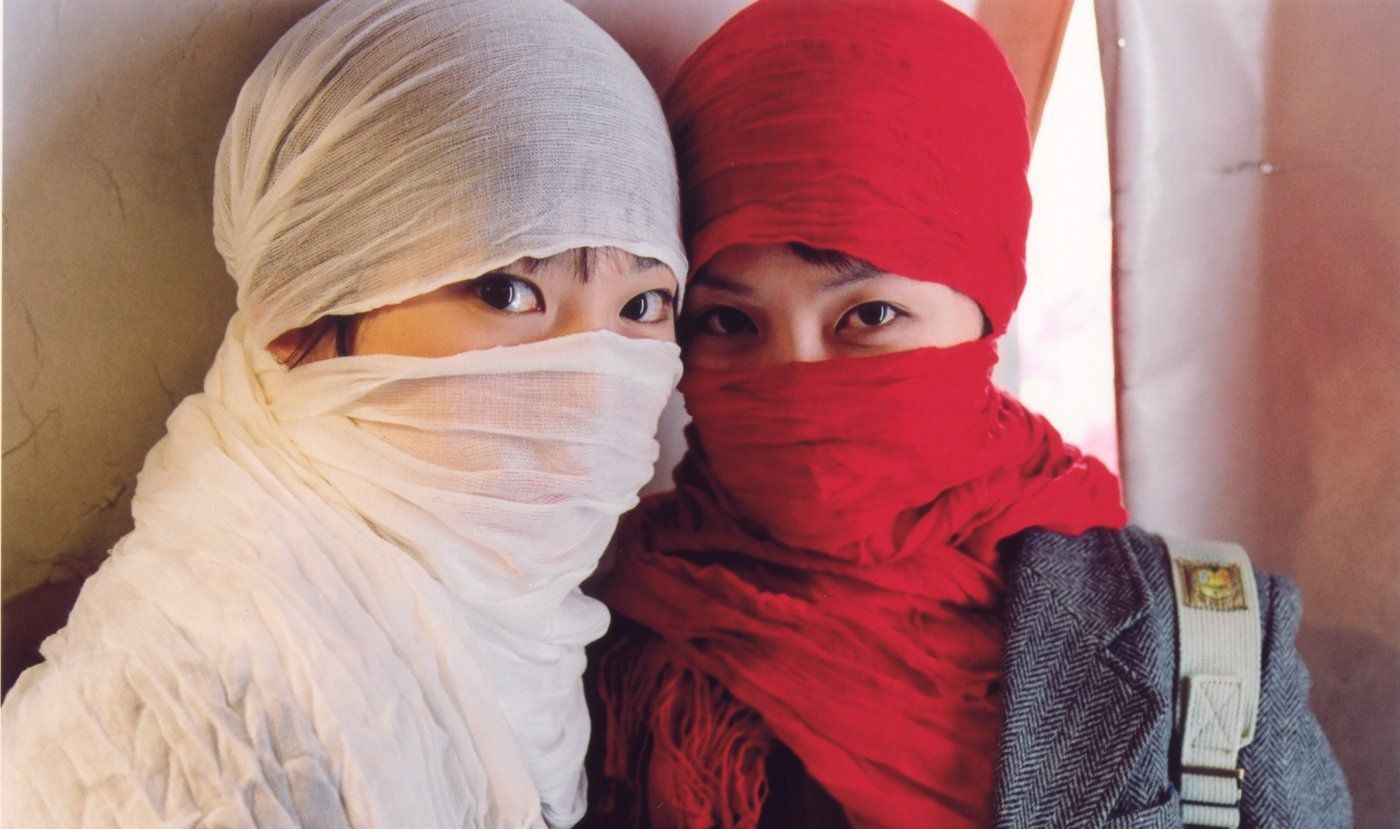

2. Samaritan Girl – Kim Ki-duk

It’s really hard to pinpoint specific characteristics and recurrences in Kim Ki-duk’s cinematic career, as the director himself has famously stated that he is like water and his films flow like water.

In “Samaritan Girl”, he films a barbarian and morbid poem to the body of the protagonist, voyeuristically observed from mirrors and windows, posing like a statue in an urban and domestic depressive nightmare that has the feel of a twisted coming of age that arrives in the form of death, graphical and sudden.

But there is some that is unquantifiable in the sheer visual power of the film, the colors and the pace, the ascetic second half and the mood swings and tone variations that make the film so magmatic and fluid and establish its power over the spectator. The film has an intimidatingly aesthetic beauty just from minimalist images and silence.

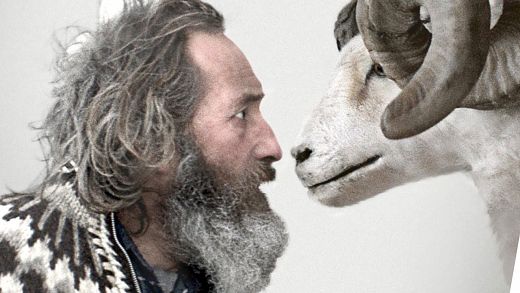

3. The Broken Circle Breakdown – Felix van Groeningen

The film probably owns the honor of having the most heartbreaking version of “Wayfaring Stranger” in cinematic history. The melodrama elements seamlessly mesh with the bluegrass soundtrack to create a synergy so exquisite that the Belgian authorities were almost certain of its Oscar win before losing to “The Great Beauty”.

Felix van Groeningen films every sequence, even the most dreamy or the most lyrical, with a sense of gritty realism that gives physical consistency to the parable of the characters, and allows their pain, their bodies, their tattoos, their wounds, and their sex organs to vibrate with the breath of life.

The film has some political undertones, but it sticks very closely to being a sad, modern country ballad where, of course, nothing ever goes well, and all that remains is singing about the next life, transcendence, but with the defeated tone of the desperate wanderer who know that there is only death.

For its evocative power, the film would have deserved the award from the Academy, even though the Oscars are nonsense, anyway. Spiritual and intimately earthly at the same time, a moving film.

4. Arabian Nights – Miguel Gomes

This film is the son of austerity and cinematic freedom. In a troubling economic era for Europe and his country, Miguel Gomes exercised his directorial freedom to its maximum extent with a six-hour epic, loosely based on Arabian Nights. The film is exotic and urban at the same time, slightly hallucinogenic, political and intimate, reminding of the cinema of Angelopoulos.

The film is a celebration of cinematic narrative, and in the interesting intro, which features Gomes himself, the director seems to give up, saying that it is impossible to make the films he wants to make. He gets sentenced to death by his own crew, but then the film starts and becomes the film he wanted to make, as though the director in his individuality is finally dead and the film is all that remains. “Arabian Nights” is everything one wants it to be, and at its core is nothing but cinema, pure cinema.

5. Effi Briest – Rainer Werner Fassbinder

Some people, rather shortsightedly, see Fassbinder as a monothematic bore, an artist that recreates his own version of transgressive queer cinema, always in the same kind of fashion. But he was, in fact, as close to Bergman-esque obsessiveness as any filmmaker in those years; his films were obsessive and about his obsessions at the same time, steady in their form and tremulous with desire and force underneath their perfectly polished surface.

“Effi Briest”, in the way in which costume dramas often do, exercises a mirror-like deception, concealing the fire that burns within the elaborate structure of the exteriority, through the use of tiny gestures and controlled performances. A comparable film might be Bergman’s “Cries and Whispers”, not so much for the plot but for the sense of boiling insanity underneath.

Of course, Fassbinder’s touch is much more tender, a connection with his female characters strengthened by his own sense of dysphoria, his fragmenting himself in numerous characters that embody Freudian metaphors for his psyche. As always, the descent into pure and inevitable solitude through the infringements of societal norms is a constant theme of his work, from which we can see the mental wounds of the director and his biography meshing with the film.