5. Dr. Strangelove or How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Bomb (Stanley Kubrick, 1964)

Another great Stanley Kubrick movie. This time, a satirical comedy about the ideological clashes between the Soviet Union and the United States, communism versus capitalism. Using basic stereotypes of the extremes between Soviets and Americans, Kubrick builds a burlesque universe enough to give off good laughs and criticism enough to cast doubt on human behavior itself.

In this top work on the Cold War, the great Peter Sellers plays three antagonistic characters. In this film, a general completely out of hand resolves to devise a plan to bomb the Soviet Union, going against the recommendation of his country, initiating a possible nuclear war. Simultaneously, the president and his other advisers seek alternatives to prevent such a plan.

Toward the end of the film, the bomb is about to be launched. Arriving at such an act, one of those in charge of such a mission, climbs on the atomic instrument and launches, like a cowboy, toward the Soviet soil. So at the Pentagon, Dr. Strangelove, who had worked in Nazi Germany, reveals his (unconscious but still alive) Hitler side.

In this way, Kubrick makes the geopolitical situation of the time appear to be a true circus of attractions. Generals, commanders, and presidents show themselves to be intemperate and dubious figures. It is, therefore, a trustworthy portrait of a society immersed in the Cold War.

4. Rosemary’s Baby (Roman Polanski, 1968)

One of the most controversial directors of modernity, Roman Polanski is also the author of several cinema masterpieces. Since “A Knife on the Water,” the Polish filmmaker was already an aesthetically adventurous director.

Growing up in his career, he produces productions with such big-time stars as Catherine Deneuve (“Repulsion”), and also films in the U.S. – see “The Tenant” and later “Bitter Moon.” Flirting with suspense and horror, the director has established himself as one of the greats in this genre.

A canon of modern horror, “Rosemary’s Baby” is the great work of Polanski. Starring Mia Farrow and John Cassavetes, the movie is about a couple trying to have a child. Finally pregnant, the wife begins to suspect that her husband and her elderly neighbors are evolved with a Satanic sect, and finally, believes that she is about to give birth to the son of the Devil.

At the end of the film, after the alleged death of her child, Rosemary does not give up her investigations and finds a hidden passage inside her apartment. Passing through the doorway, she finds her husband and countless others participating in what once seemed improbable: a cult of Devil worship.

Initially astonished, the protagonist goes to the cradle of her son and, encouraged by the cult participants, starts to take care of this demonic creature. In this scene, paranoia, insanity, dissimulation, and amazingly, a love for the child make themselves present, leaving “Rosemary’s Baby” as one of the most intriguing and terrifying movies in film history.

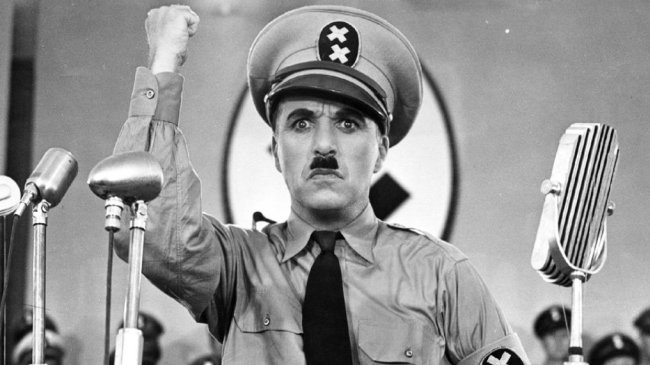

3. The Great Dictator (Charlie Chaplin, 1940)

One of the great films about fascism during World War II. In his first spoken film, the famous British director criticizes harshly the governmental system popularized by Adolf Hitler and Benito Mussolini. In “The Great Dictator,” Chaplin narrates the story of a modest Jewish tradesman who is pursued by a tyrant dictator, Adenoid Hynkel. However, during persecution, the tradesman is mistaken for the governor.

The final scene is a mark in world cinema. Acting like the dictator, the tradesman is called to make a speech to his soldiers and adapts. Then, instead of saying what was expected from a authoritarian leader, the humble citizen preaches an humanitarian speech of union among the people.

In only shot, with just a quick insert, the line is constructed in a convincing and credible way. A strong and desperate request for a united and peaceful world marks the end of the movie and stays alive in the collective subconscious. At the end of the speech, he breathes heavily, as if humanity had arrived to its limit in the matter of trying to ease world’s pain and suffering.

2. Stalker (Andrei Tarkovsky, 1979)

Being one of the countless masterpieces of the Soviet master Andrei Tarkovsky, “Stalker” is clearly the pinnacle of his cinematography. With his usual philosophical thematics and the almost observing camera, Tarkovsky keeps a conformity in his filmography on a whole. Adding all his usual language traits to series of dense dialogs, “Stalker” is a genuine mark in world cinema.

The movie is about three travelers who enter a territory forbidden by the government: The Zone. The ‘Stalker,’ the one that guides the others, takes two other men with him: the ‘Professor’ and the ‘Writer,’ According to some tales, inside the Zone is a room which whoever enters can have their wishes come true. Undergoing situations that cause danger to their lives, the three debate about their motivations to enter in a place forbidden by the government.

Its finale shows the stalker’s daughter, named Monkey, watching a glass of milk on her desk as she hears a train pass near her house. Suddenly, the vessel begins to tremble and finally falls. Recorded in only one shot, this ending is able to resignify the trip from the Stalker to the Zone.

At the beginning of the film, the protagonist and his wife debate about the health of their daughter and how they want her to recover soon from her illness. Was the Zone capable of realizing unconscious desires like that of Monkey’s father in relation to her well being, giving her telekinetic abilities? Or does the glass just fall by the force created by the train? Such poetic ambiguity makes the end of “Stalker” a great mystery for Tarkovsky lovers.

1. 2001: A Space Odyssey (Stanley Kubrick, 1968)

Stanley Kubrick was one of the most versatile filmmakers of all time. A satirical comedy about the Cold War (“Dr. Strangelove”), a disturbing drama about a pedophile (“Lolita”), an epic movie about Spartacus (“Spartacus”), an amazing work of science fiction (“2001: A Space Odyssey”) and a dystopian ultra violent movie (A Clockwork Orange).

Those are some of the themes of Kubrick’s masterpieces. Despite all of this, the American director’s films have never been nominated for the Best Picture award at the Oscars. In his whole career, he never had his deserved recognition from the Academy, but in festivals around the world, his movies almost always had success.

One of the most enigmatic movies of all time, “2001: A Space Odyssey” still echoes in the minds of those who were young in the ‘60s. The incredible Kubrick explored the dense universe of sci-fi and succeeded.

His movie is divided into multiple chapters that make a giant ellipsis in human history. Beginning in prehistory, the movie cuts to a lunar space station, where a mysterious monolith intrigues scientists. Years later, aboard the Discovery spacecraft, David and Frank are sent to Jupiter to investigate the origin of the monolith.

After surviving the arrival at Jupiter, David arrives in a white room of French architecture with his own figure, but older, lying in a bed, on the verge of death. In such a dream scenario, the monolith that appears suddenly becomes a gigantic fetus floating in space. Here, surrealism, symbolism, and mystery take over the atmosphere. There are no explanations or theories.

The end of “2001: A Space Odyssey” is a summary of everything the film sets out to display: meanings created from the subconscious of each viewer, escaping from the rationalism present in most films that have already been made.