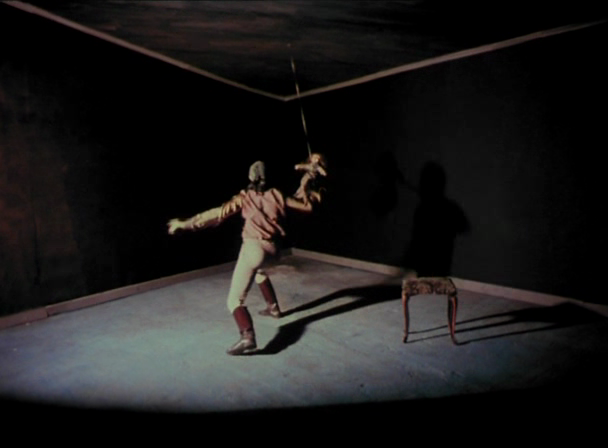

17. The Angel (1982, Patrick Bokanowski)

This little-known (criminally-underseen with a mere 350 votes on IMDb at this time of writing!) French experi-mental/avant-garde silent is, like the previous film on this list, a plotless/non-narrative series of performance-art-like tableaux experiences of life, based, again, much more on acting, faces, bodies, emotions, feelings, vocal/verbal and physical/behavioral tones and shifts, psychology, etc. than on decoding emotionally-empty and mechanis-tic/lifeless camera positions/movements in order to “get” some banal message or as substitute for emotional understanding of self and character.

And exactly like that film, it seems like Patrick Bokanowski’s film, whose original French-language title is L’Ange, recorded the worst nightmares one can possibly have out of one’s brains dur-ing sleep.

18. Klassenverhältnisse (1984, Danièle Huillet and Jean-Marie Straub)

France’s Nouvelle Vague/New Wave movement, with several notable (though largely neglected) exceptions – e.g. Alain Robbe-Grillet, Jacques Rivette – was by and large an artistic and aesthetic failure. Too much focus on imitating (and worshipping) the worst Hollywood action/thriller explosionfests.

On predetermined conceptual ideolo-gy/politics and philosophy as substitute for the perceptive-perceptual/emotional com-plexities of life and truth-based learning-experiences emotionally-wise on the view-ers’s part, on pseudo-“complex” “cinematic language, devices, expression, and gaze” i.e. on decoder-ring camera movements/angles/positions and editing tricks/techniques easily understandable within two seconds as substitute (for understanding of self and character) for the hard work required on the audience’s part with the actors’s physical, facial, and tonal shifts and turns that actually required knowledge and experience of life’s complexities (not to mention a lack of interest in life) and an adolescent-macho/dudebro fetishizing of le cinéma with the deriding of non-visual media.

On grand themes and messages, especially if easily-decoded/deconstructed and under-stood through said “purely cinematic devices” (and especially if in line with political-ly-correct notions of middle-class/bourgeois “social importance”) over capturing the allegedly “small” moments of life. On schmaltzy sentimental bourgeois melodramatics à la “nobody understands you and adult society is just a bunch of dirty tricks, so be a real man and rebel against authority” pandering to the nostalgic-for-lost-innocence psychology of teenage boys with their angst, etc.

Whence the supposed “criticism” of films’s “amateurish” “lack of cinematic gaze, expression, devices, and language” even if they are dealing with the complexities of life and human-beings in favor of Holly-wood. And the fact that most self-styled so-called “film-buffs” cannot really describe what they like about their favorite films except for “the usages of cinematic gaze and language” namely that anything in them is crystal-clear and that they are spoon-fed how they are supposed to feel instantly at every moment.

Probably the best exception to the aforementioned rules was the husband-and-wife filmmaking-team of Danièle Huillet and Jean-Marie Straub, who not for nothing largely worked outside France. Their Bressonian eschewal of those tricks lead to an actual experience of and an en-hancing/enriching understanding of life as a truth-based learning emotional experience.

In their highly experimental/avant-garde Klassenverhältnisse, which currently has only 423 votes on IMDb, one of the darkest portrayals of alienation/class-struggle has been put to screen. Rather than evoking reptilian emotions thrillers invoke and rather than creating characters that are mere archetypes, this duo filmed emotions that matter and people hard to pin. The original German-language tittle can be best translated as “class relations.”

19. White Material (2009, Claire Denis)

Like Philippe Grandrieux, Claire Denis has been associated with the Bressonian New French Extremity movement. And just like him, she wishes to bestow upon her audiences new experiences rather than having them stay put in their comfort zones. Let alone experience merely the most reptilian ones as in standard and mundane Hollywood button-pushing fight-or-flight thrillers.

Somewhat similarly to Lars von Trier’s Dogville (2003) and Manderlay (2005), this film eschews both the Hollywood idea of “identifying with a character” as a prerequisite for a film being good (i.e. staying within one’s comfort zone without actually learning anything) and the politically-correct bourgeois/middle-class idea, fa-vored by those devotees of lachrymose so-called “social justice” “film theory,” which is just another way of saying that one wishes not to be challenged but rather to stay in one’s comfort zone by merely having one’s predetermined ideology, to whom one never actually given any thought but merely adopted uncritically, parroted back and confirmed, of excusing the inexcusable in the case of allegedly innocent/angelic black-and-white (though naturally “social justice” “film theory” prides itself on its alleged complexity-of-thought and open-mindedness) “victims.”

The bigotry of low expecta-tions and the naïve adolescent rebelliousness of misplaced empathy are engaged with by Isabelle Huppert in the role of a lifetime. As critic Amy Taubin notes in her Criteri-on Collection DVD insert, “[a] decade or two after the end of colonialism, the former ruling class is no longer welcome, [m]ost French whites have departed, but a few hold on, in denial about the fact that they’ve lost their power or, in the case of Maria Vial (Isabelle Huppert), who runs the coffee plantation that belongs to her ex-husband’s family, too in love with the land to which she has devoted all her energy to give up[, a]nd where would she go? Maria can’t accept that, for the Africans she’s known all her life, she is now ‘white material,’ easy to dispose of and less than human.” Uncom-fortable and politically-incorrect in our so-called intellectual-dominated era to say the least.

20. L’eclisse (1962, Michelangelo Antonioni)

Like Danièle Huillet and Jean-Marie Straub and Robert Bresson, Michelangelo Antonioni was not known for nothing as the master of alienation. Eschewing “plots” and “storytelling” – nothing is more plebeian and philistine than the petite bourgeoisie obsession with “spoilers” – this is Antonioni’s most experimental film.

A portrayal of a doomed affair (the ending, in which neither of the two lovers appear at the location in which they set up their date, remains one of the most harrowing, tragic, and intense in the entire history of cinema, emotionally-speaking), it remains one of the greatest representations, to say nothing of an outright bestowal of the experience in and of itself on the viewer, of alienation and loneliness ever put to screen.

In the words of critic Gilberto Perez, writing for the Cri-terion Collection DVD insert, “[e]ven at the end of L’eclisse, when the awaiting cam-era registers, around the suburban corner where the protagonist couple are supposed to meet, the uneventful daily passage from afternoon to evening, daylight to twilight, twilight to darkness, a clipped series of images holds a conclusion in unsettling abey-ance.”

And Antonioni himself, also writing for the Criterion Collection DVD insert, opined that “[b]efore shooting L’eclisse, I went to Florence to see—and shoot—an eclipse of the sun[, i]n that darkness, in that icy cold, in that silence so different from all other silences, in that almost complete motionlessness, those pale, earth-colored faces, I speculated whether even sentiments are arrested during an eclipse[, i]t was an idea that was only vaguely connected with the picture I was making, which is why I didn’t retain it[, b]ut it could have been the nucleus of another film[, t]he most diffi-cult thing is to recognize an idea out of the chaos of feelings, reflections, observations, impulses that the surrounding world stirs up in us[, a]mong thousands of possibilities, why do we isolate one idea, that one and not another? There are a thousand ways to answer this, none of which is satisfactory[, a]ll I can say is that, having singled out a theme, I generally let it ripen for quite a while. I think it helps not to make it mature right away, never to chase after a film, let the film come along very gently by itself[, i]t almost always comes [at] night.” The original Italian-language title translates to “the eclipse.”

21-23. The Second Awakening of Christa Klages (1978); Sisters, or the Balance of Happiness (1979); Sheer Madness (1983) Dir. Margarethe von Trotta

The whole way people get stuck up and sucked up into macho/juvenile/adolescent naïve ideologies, politics, and philoso-phies of political rebelliousness against authority and “the system,” so much that it takes up and screws-up their whole lives/being, no doubt inspired in no small part by the Rote Armee Fraktion/Red Army Faction current in Germany around the time of the film’s making, is the focal point of Margarethe von Trotta’s film, with the original German-language title Das zweite Erwachen der Christa Klages, one of the neglected figures of the Neuer Deutscher Film/New German Cinema, which currently sports on-ly 215 votes on IMDb.

Three people rob a bank to help a day care center debt, and one of them, the titular Christa, escapes to Portugal in a desperate attempt to hide. Her friend Ingrid visits her and their relationship makes the collective “nervous,” so-to-speak. And von Trotta continues with this theme further.

With only 174 votes current-ly on IMDb, Margarethe von Trotta’s 1979 dark adult fairy-tale, Sisters, or the Bal-ance of Happiness, whose original German-language title is Schwestern oder Die Bal-ance des Glücks, is about sisters Maria and Anna.

The former a well-adjusted secretary, the latter a depressive personality who takes . When Maria’s relationship with her boss’s son starts to lead to love, Anna takes a selfish and drastic step that plummets and sends Maria into solitude.

One of the greatest attempts to realistically portray de-pression, alienation, and loneliness, von Trotta’s film, like all of her films, only gains by not utilizing a “cinematic gaze, expression, device, and language” and by leaving her style-free camera merely functional, focusing instead on a realistic emphasis on acting and emotions, bodies and faces, psychology and feelings, tonal and vo-cal/verbal shifts and turns.

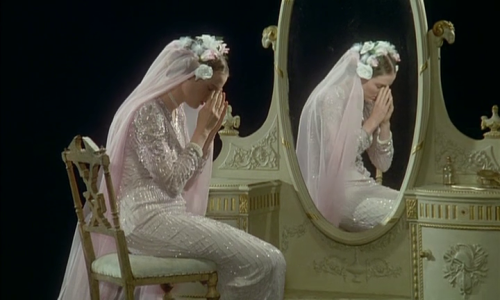

Starring Hanna Schygulla and Angela Winkler, two bril-liant and beautiful actresses of the Neuer Deutscher Film/New German Cinema, Mar-garethe von Trotta’s greatest masterpiece, 1983’s Sheer Madness, whose original Ger-man-language title is Heller Wahn, and her most autobiographical, which has only 189 votes on IMDb currently, explores the fine line between madness and creativity.

Con-tinuing on her recurring theme of female camaraderie, a university lecturer, Olga, en-courages a mentally-ill painter, Ruth, to place her works at a gallery, only for her at-tempts to be thwarted by her husband (loosely based on one of von Trotta’s exes). This extremely emotionally-intense film ends with Ruth shooting him after discover-ing his involvement with the gallery cancelling her exhibitions. The following entry is tangential to this issue.

24-25. The Future of Emily (1984); My Heart Is Mine Alone (1997) Dir. Helma Sanders-Brahms

Helma Sanders-Brahms’s (an-other neglected Neuer Deutscher Film/New German Cinema genius) emotionally-grueling Bergmanesque portrayal of a neglectful career-woman actress/mother’s un-derstanding that she missed the joys of life by not becoming a stay-at-home-mother like her own mother is one of cinema’s underrated tragedies and has only 35 votes on IMDb.

Sanders-Brahms’s films are concerned neither with reptilian “plots/”“stories” nor with abstract ideas derived by decoding so-called “cinematic gaze, devices, and language,” The original German-language title is Flügel und Fesseln. Helma Sanders-Brahms’s 1997 expressionistic cinematic poem, My Heart Is Mine Alone, which sports the original German-language title of Mein Herz – niemandem!, is her most experi-mental/avant-garde film.

It sets a great deal of its action on nearly-empty sound stages, à la Hans-Jürgen Syberberg’s Hitler, ein Film aus Deutschland (Hitler: A Film From Germany, 1977) or Lars von Trier, which included little more than actors delivering monologues, once again, demonstrating how “uncinematic merely filmed literature and theatre without any usage of cinematic gaze, expression, devices, language, etc.” that actually requires the viewers to have some knowledge of life and create meanings out of difficultly-working with the actors’s bodies, faces, physical and to-nal/vocal/verbal shifts and turns, dialogues, etc., by learning about life and emotions and by experiencing truth-based experiences, is vastly superior to the Hollywood method of creating shortcuts to understandings of self and character by having view-ers merely decode camera angles and understand everything within two second by not learning anything that matters and by not requiring them to know anything that mat-ters.

With merely 17 (yes, seventeen!) votes on IMDb, this easily takes the cake quan-titatively-wise for being the most criminally-underrated film of all times. Featuring artistic works by real-life personages such as the notable expressionist painter Marc Chagall [3] and dealing with the real-life ill-fated romance between a Jewish poetess and a Nazi poet in pre-World War II Germany.

Many of Sanders-Brahm’s films could have appeared on this list. And, I shall conclude it by noticing the semantic similarities between “darkest” and “infamous” and imploring those reading who have not read it yet to also read my previous list dealing with the most infamous films in cinematic his-tory, many of whom could just as well have appeared here too (and vice-versa, of course).

Note: All the sources of citations in this article can be found in this page.

Author Bio: Mr. Gal Ben-Kochav, B.A., M.A., received his B.A. (2013) and M.A. (2016) in Sociology and Anthropology from the School of Social and Policy Studies, Gershon H. Gordon Faculty of Social Sciences, Tel Aviv University. He spent the last couple of years writing a (yet-unpublished) draft of a lengthy scholarly monograph, in Hebrew, dealing with the application of evolutionary psychological theory in the study of social (ethnic- and sex-based) stratification and structure in Israel, currently standing at 1,086 single-spaced pages in Times New Roman standardized at a font of 12. He has long been interested in art, avant-garde/experimental, and independent cinema.