7. Ghost Dog: The Way of the Samurai (1999)

Ghost Dog is, simply put, just another one of those hip-hop gangster movies infused with Japanese warrior folklore, filtered through the French existential thrillers of Jean-Pierre Melville, with a splash of Seijun Suzuki for added sting. Got that?

Forest Whitaker astounds as the eponymous Ghost Dog, a contract killer without peer, also the retainer of a Jersey City-based Mafia don named Louie (John Tormey), who saved his life years ago.

An obvious homage to Melville’s Le Samouraï (1967), Ghost Dog is an imaginative, stylish, surreal fever dream of a film with a poignant lead performance from Whitaker, a genius score from Wu-Tang Clan’s RZA, and the familiar flourishes and arthouse embellishments that Jarmusch fans have come to expect.

That said, this is a melancholic, meditative, and anodyne affair, and not your typical action-thriller at all. If you like your films subversive, off-kilter, deliberately paced and unpredictable than you better bay at the heels of Ghost Dog.

6. Paterson (2016)

“I think Paterson is more of a film in the form of a poem rather than a poem in the form of a film.” –– Jim Jarmusch

Paterson is a subtle and swift charmer about the everyday delicacy and grace that’s all around us. Adam Driver in the eponymous role is a working-class poet in the small Jersey town that shares his name.

A poetic diary film, the episodic nature of Paterson’s routine––the film occupies a typical week in his life––gracefully finds glory in place and person in ways that are truly and understandably profound. Paterson proves that Jarmusch may be some kind of guru; part Zen master and part indie auteur, as he reminds us in his droll and wonderful way that beauty is everywhere.

5. Stranger Than Paradise (1984)

Voted the Best Picture of 1984 by the National Society of Film Critics and recipient of the Caméra d’Or at the 1984 Cannes Film Festival, Stranger Than Paradise was a watershed motion picture for Jarmusch.

Writing for the New York Times, critic and columnist Lynn Hirschberg called remarked that the film “permanently upended the idea of independent film as an intrinsically inaccessible avant-garde form” and it established Jarmusch as the savior of the American indie milieu.

John Lurie is wonderful as Willie, a New York City layabout and a bit of a goof-off who pals around with Eddie (Richard Edson). Their day-to-day is punctuated by card-sharking, TV dinners, and barley pops.

When Eva (Eszter Balint), Willie’s 16-year-old cousin from Budapest, drops in rather unannounced, it’s not long before he warms to her and soon finds himself braving Cleveland and later Florida to be a better uncle and to battle ennui in a rather low-key but satisfying fashion. While not a whole lot really happens in Stranger Than Paradise, it’s a character driven and atmospheric affair, with dry humor at every step, and it’s all done with great care and a fascinating cleverness.

4. Dead Man (1995)

According to author and film critic J. Hoberman, “[Dead Man] is the Western Andrei Tarkovsky always wanted to make”, and considering the existential, post-modernist, and apocalyptic statements issued in Jarmusch’s film, Hoberman speaks unadulterated truth.

Using his signature minimalist and informed style, Jarmusch cast Johnny Depp in the title role as William Blake, a visitor to the Western frontier, who also, cruelly, isn’t long for this earth.

Depp’s Blake is a deliberate literary allusion to the 18th century poet—a repeated reference is that Blake’s poetry exists in the bullets of his gun—and Dead Man cascades such suggestion. It’s as if the film couldn’t exist in a post-Blood Meridian, post-Place of Dead Roads universe (Revisionist Western novels of great weight, by Cormac McCarthy and William Burroughs, respectively).

Reluctantly partnered up with a Native American named Nobody (Gary Farmer), a Virgil to Depp’s Dante, they embark on a funerary dirge that won’t end in their favor. Dead Man offers an inspired list of crazy cameos (including Robert Mitchum, and Iggy Pop), a riveting score by Neil Young, and, more perversely, an unconventionally damnable treatment of capitalism, racism, and violence. The darkest, most shocking film in Jarmusch’s oeuvre, it’s also his most far-reaching.

3. Only Lovers Left Alive (2013)

Eve (Tilda Swinton) is one part of an incurably cool vampire couple whose husband, Adam (Tom Hiddleston) is having self-harming thoughts in Jarmusch’s chic shocker, Only Lovers Left Alive.

Tough-as-nails and fiercely romantic, this vampire film is full of leitmotifs involving fear, exhilaration, alienation, isolation, creativity, art, music, literature, life, and death. It’s not full-on in your face horror but it does have classic Gothic sensibilities, jets of blood, moments of mortal fear, piercingly sad genuflections, and painfully poignant ruminations on unending love.

More visual than it is verbal, this elegiac and eerie film displays, amongst other things, the wraithlike dissolution of Detroit, the unearthly otherness of Tangier and many amusing and macabre tableaus of the undead, their uncanny mores and their outlandish dwellings. Only Lovers Left Alive is a visual spree detailing the haunting harmony of ageless sweethearts in perpetual midnight and it’s marvellous.

2. Mystery Train (1989)

A personal favorite amongst many of Jim Jarmusch’s diehard adherents––it’s my number one and I never tire of watching it––the musical pedigree alone in this marvellous 1989 anthology film, an exuberant love letter to Memphis and its melodies, astounds.

Heartfelt, hilarious, and tragic turns from the likes of Rick Aviles, Steve Buscemi, Masatoshi Nagase, Youki Kudoh, Joe Strummer, Rufus Thomas, Screamin’ Jay Hawkins, and a clever cameo from Tom Waits (stealthily reprising his role from Down By Law) help make this film an out and out atmospheric reverie.

John Lurie’s score is sublime, the misty ‘round midnight music is haunting, while the fractured narrative enchants all the way. Robby Müller’s cinematography is superb as ever, with tracking shots that linger long in the memory, and all those quirks and embellishments that make Jarmusch so singular are all on bright display.

Mystery Train is an anecdotal delicacy with lovable, pitiable, and sympathetic characters that somehow feels like a lucid, lively dream, one that’s listless, lovely and neon-lit. Wonderful.

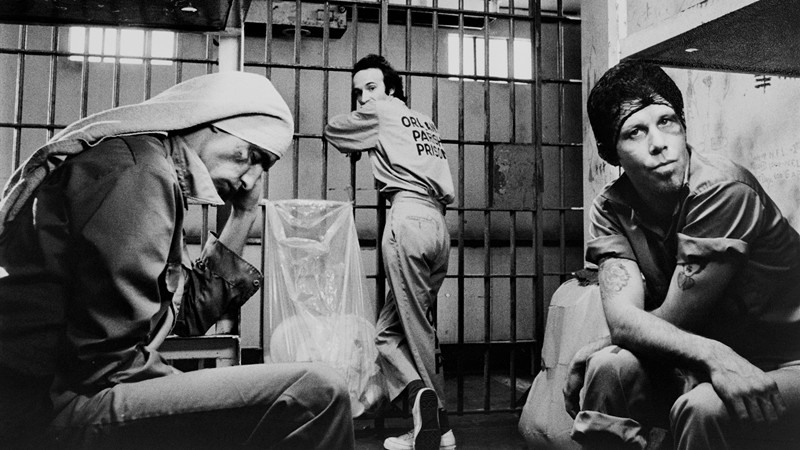

1. Down By Law (1986)

“It is a sad and beautiful world.”

Incidental encounters and tough luck reluctantly come together in writer-director Jim Jarmusch’s deeply distinctive third feature, and arguably his showpiece, 1986’s Down By Law. Existing in its own even tempered and hermetically sealed cosmology, joyfully noncommercial and fancy free from the liens of box-office revenue, this is a funny film of unexpected affections, reluctant friendship, and fluky kindred spirits.

Dislocating Jarmusch to the Deep South of New Orleans, Down By Law is affectionately photographed by Robby Müller’s flush monochrome––this is a movie firmly inveterated in the mind of its maker and in what Jarmusch has jovially described as a “neo-beat-noir-comedy”.

Telling the tale of the unlucky interconnected lives of a trio of ne’er-do-wells; Jack (John Lurie), a shrewd pimp; Zack (Tom Waits), an unemployed radio DJ known by the on-air persona Lee “Baby” Sims; and Bob (Roberto Benigni, in his very first international role), an ill-fated Italian tourist with a loose grasp on the English tongue. The director’s distinctiveness, style, and sympathies make for a wonderful resistance to the usual conforming Hollywood ticket.

Down By Law plays it incredibly, impassively cool, and yet somehow ripens into a rapturous and sunny yield. Ultimately, the film plays generously on the psyche and the senses before it all ends rather elegiacally as an imaginative and meaningful American fable. Essential and unforgettable viewing.

Author Bio: Shane Scott-Travis is a film critic, screenwriter, comic book author/illustrator and cineaste. Currently residing in Vancouver, Canada, Shane can often be found at the cinema, the dog park, or off in a corner someplace, paraphrasing Groucho Marx. Follow Shane on Twitter @ShaneScottravis.