6. La Nuit Américaine

Infamous for starting a feud lasting over a decade between prominent French New Wave figures Jean-Luc Godard and Francois Truffaut, La Nuit Américaine, released in 1973, is nevertheless one of the latter’s most critically acclaimed film.

In short, it is the story of an ardent director attempting to wrap up his film’s, titled Je vous présente Paméla, principal photography while continuously having to cope with the multiple issues generated by his cast and crew. In other words, it is a truthful film about filmmaking.

Appropriately, what makes this movie all the more interesting is the fact that its director, Francois Truffaut, is the one playing the director of Je vous présente Paméla which coincidentally stars the french director’s frequent collaborator Jean-Pierre Léaud.

Hence, in doing so, Truffaut knows his viewers automatically associates them both as being, as mentioned previously, frequent collaborators. Thus, Francois Truffaut purposefully takes advantage of this fact in order to add an entire new layer of realism to his film’s structure.

That said, La Nuit Américaine stays true to the numerous challenges a film production needs to work through in order to obtain a finish product. Hence, Truffaut certainly doesn’t sugarcoat the procedure yet definitely portrays it in a comedic way, therefore giving his audience the possibility of viewing La Nuit Américaine as a subtle satire of Hollywood productions.

7. Mulholland Drive

Praised, among many things, for it’s puzzling narrative and oneiric aesthetic, it should come as no surprise that David Lynch’s 2001 release titled Mulholland Drive is widely regarded by critics and scholars as the best film of the 21st century. It is a surreal tale of love and jealousy underlined by a critical viewpoint on the Hollywood filmmaking industry. Or to quote one of the film’s marketing tagline; “A love story in the city of dreams…”

That said, Mulholland Drive probably won’t make any sense at first viewing. Yet, compared to other nonlinear narrative features that are simply nonsensical, David Lynch takes advantage of that particular narrative structure to portray both the reality and illusionary world of the film’s dual identity protagonist played by Naomi Watts.

Hence, similar to Billy Wilder’s Sunset Boulevard (1950) that depicts the delusion of an aging silent era film star, Mulholland Drive explores the repercussions the so-called city of dreams has on aspiring actresses.

Moreover, just as Sunset Boulevard reflects the transition from one type of cinema to another, such as the silent films to the talkies or synch-sound pictures, Mulholland Drive, in its own right, reflects the transition from the post-classical cinema to modern. Accordingly, David Lynch communicates this through his use of structure and temporality thus making Mulholland Drive a modern masterpiece.

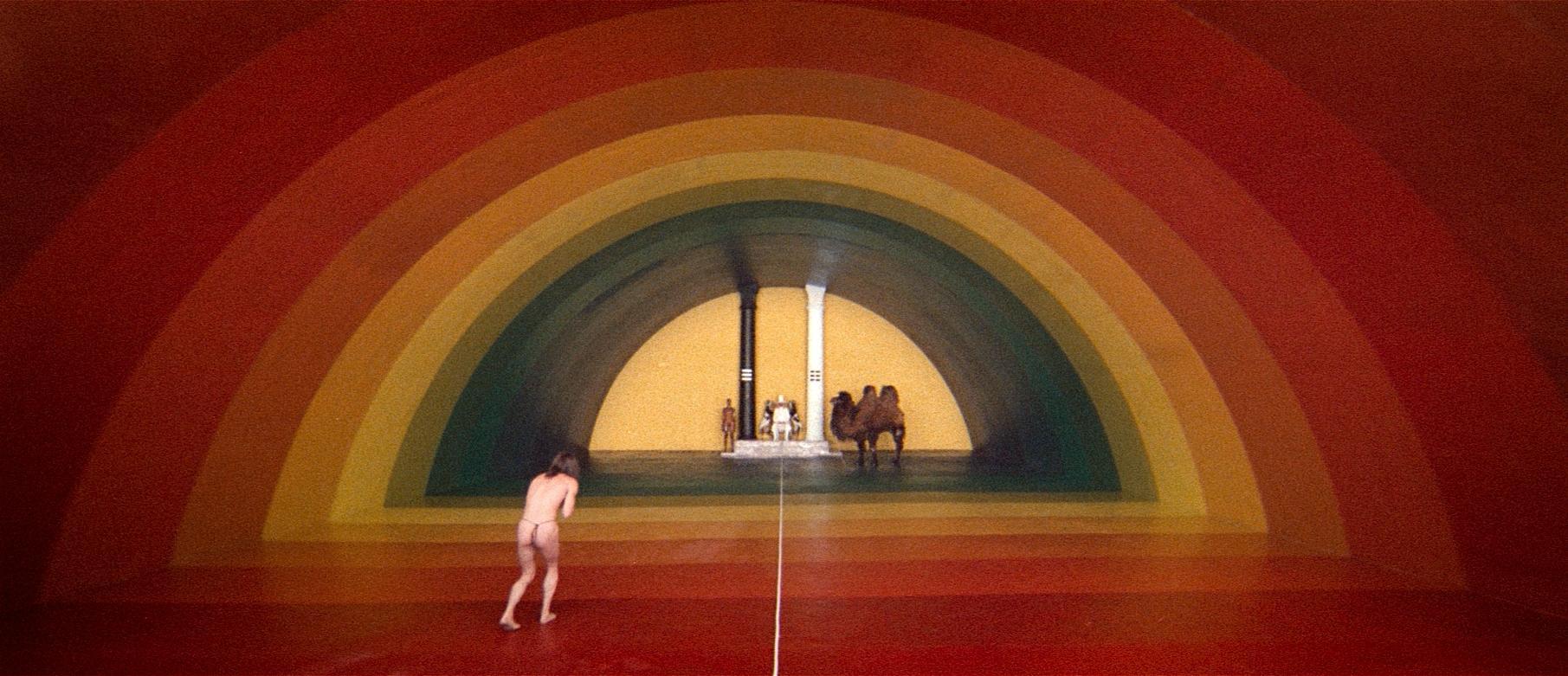

8. The Holy Mountain

Alejandro Jodorowsky’s The Holy Mountain is all but a conventional film. In fact, released in 1973, this Mexican production caused quite a stir around the world as well as a scandal at the Cannes Film Festival with its existential symbolism and blasphemous imagery. That said, Jodorowsky’s psychedelic masterpiece is nevertheless considered today as one of the greatest cult film.

As a film heavily charged with theological and existential symbolism, The Holy Mountain is much more communicated through imagery than dialogue. In summary, it follows a group of eight individuals chosen and guided by The Alchemist, played by the film’s director, through a spiritual journey to the top of the Holy Mountain in search of enlightenment. Ergo, The Holy Mountain is open to many interpretations and most likely signifies something different for every one of its viewer.

Accordingly, the reason this movie stands out so astonishingly is because of the ending. While guiding the film’s characters through multiple spiritual awakenings as The Alchemist, Alejandro Jodorowsky, as the director, is also consciously leading his audience to one of the most beautiful self-reflexive moment in cinema history which, deliberately plays as the enlightenment.

9. Beware of A Holy Whore

Initially banned due to strict censorship in West Germany, Beware of A Holy Whore is now considered one of Rainer Werner Fassbinder’s most critically acclaimed film. Released in 1971, it chronicles the life of a film crew that consumes an endless amount of alcohol while indulging in sexual relations in a secluded Spanish hotel as they are waiting for their director and film stock.

Hence, Beware of A Holy Whore explores the alienation a film crew can experience during a film shoot. In fact, not only is this picture critical of the production process but also plays out as semi-autobiographical since it is widely based on situations that had occurred during Rainer Werner Fassbinder’s latest film in that same year titled Whity.

Thus, Beware of A Holy Whore might be the most personal look inside the young german director’s work environment even though it was only his tenth feature film amongst an impressive repertoire of over forty productions in thirteen years.

10. Synecdoche, New York

Released in 2008, Synecdoche, New York starring Philip Seymour Hoffman as its protagonist is writer Charlie Kaufman’s directorial debut, and what a spectacular debut it is. It follows the life of a theatre director named Caden Cotart who is attempting to create an elaborate play taking place in a life-size replica of New York City while simultaneously suffering from an existential crisis.

That said, Synecdoche, New York is an exceptionally complex story in which Charlie Kaufman creates a multi-layered narrative that delves into his protagonist’s psyche. In other words, the film explores how writers project their own desires, fears and melancholy through their work in order to further discover themselves. Hence, in doing so, the viewer experiences every stage of the creative process of a deranged play writer who is ultimately trying to reflect his own life into his magnum opus.

Accordingly, Philip Seymour Hoffman’s character’s untitled masterpiece very distinctly reflects the bigger picture it plays in; Synecdoche, New York. Thus, Caden Cotart clearly plays Charlie Kaufman’s alter ego even though the former’s magnum opus is a play, whereas Kaufman’s is this very movie.