8. A Fistful of Dynamite (1971)

Historically, and depending on your source, this film, alternatively titled “Duck, You Sucka!”, is either Sergio Leone’s weirdest, worst, or most underrated film. What it is somewhat of a buddy movie in which an explosives expert named John Mallory (James Coburn) teams up with mercenary Juan Miranda (Rod Steiger) to rob a bank during the Mexican Revolution. While many lament the lack of iconic moments when placed in cannon next to Leone’s other films, the ensuing years have lead many to recognise what the film does possess in its favour rather than the aforementioned.

Morricone’s score is audaciously ubiquitous. It is an odd tune, but infectious. The enhanced color and spectacle finds itself in tandem with the most absurd humour of Leone’s career. The opening shot alone may have one baffled, in hysterics, or both at once. Sequences like on in which the upper class jaws are seen munching on their lunches in close-up aboard a train are undeniably original. Enhanced editing and special effect techniques find their place also. The film ends quite literally with a bang and, for many, succeeds in having you reminisce about its central characters and their adventures long afterwards.

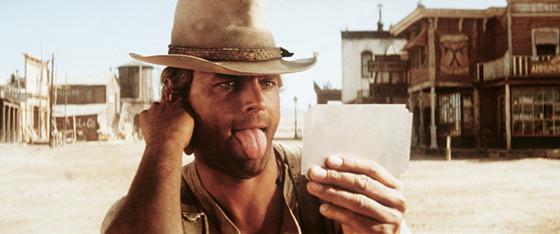

7. My Name Is Nobody (1973)

It may have been seen by many as simply an excuse to have Henry Fonda return to the Spaghetti Western, but My Name is Nobody is celebrated for craft in its own right and is often cited as a favourite amongst fans of the genre. Often cited as a comedy (many films in the genre are in hindsight identify in this light), it concerns an ageing gunslinger named Bearegard (Fonda) who wishes to resign from limelight and legend, and young gun “Nobody” who (Terrence Hill), who wishes to take his place. What ensues in best categorised as a stylish sitcom about the generation gap; with Fonda relishing his role as an old sage too smart for many a young upstart.

Bookended by scenes in a barbershop, the film centers around somewhat of a cold war between Fonda and Hill’s charatcers, publicly fueding, but privately learning from each others respective strengths and weaknesses. The actors seem to relish in their scenarios, both violent and comic alike. Those who wish to kill Beauregard provide much room for a grand finale, which centers around a railway line. The usual kinetic camerawork of the genre assists in occasional low-brow humour, a distinct direction for a western. Consider this, if you like, to be the most acclaimed example of the lighter side of Spaghetti Western oeuvre.

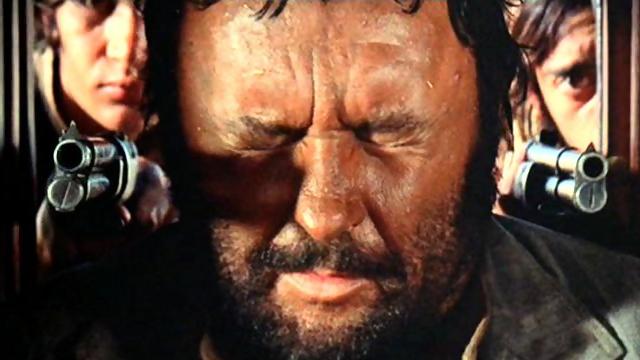

6. The Great Silence (1968)

This 1968 epic from Sergio Corbucci has been noted for it’s bleakness, maturity, and its grandiose acting. It is set distinctly in a snow-covered landscape, one which sets it apart from many of the other classics of the genre. The film’s plot situates it firmly in the hired gun oeuvre. Set in the small town of Snowhill, Utah during the great blizzard of 1898, the quaint town has fallen victim to criminal activity. None are more diabolical than ruthless hitman Loco (expertly played by shrewd thespian Klaus Kinski). When Loco marries her husband, Pauline hires mute gunfighter Silence to avenge her husband’s death and kill the merciless Loco.

It’s performances and setting carry much romance, but the film is nonetheless noted for being every bit as bleak as the perpetual snowstorm in which it is set. The sight of Kinski dressed in black riding out of the snow is fittingly chilling. The ending in particular may challenge some; serving as an emblem that sets The Great Silence apart as perhaps the bleakest and most morose of all films in a traditionally exuberant genre. This, like the great actors that perform in it, may serve to give the film a measure of extra weight.

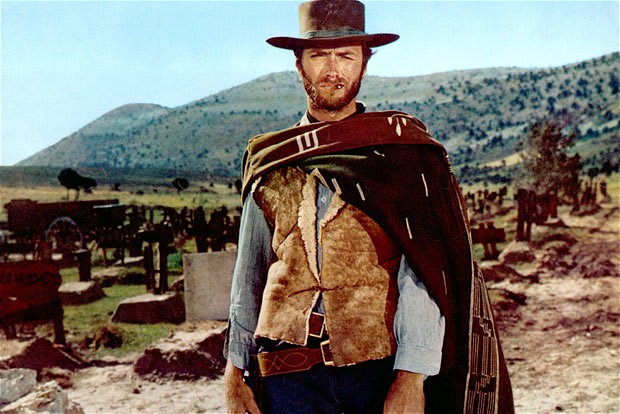

5. A Fistful of Dollars (1964)

Sergio Leone’s 1964 tale of a drifter’s vigilante justice in a small town plagued by villains is often mistakenly cited as the film that spawned the Spaghetti Western genre as a whole. It did, however, awaken the wider world to the genre.

Furthermore, it marked the first appearance of Clint Eastwood in the now iconic role of “Blondie”, the so-called “Man with No Name”. Leone knows his genre well. The premise of the wandering drifter was already a staple of classic westerns like “Shane” and “The Searchers”. The vigilante dogma of the film had been seen before, but Leone’s style broke new ground in a way difficult to anticipate. It is hard to feel anything but a sense of cinematic revolution at play here.

The Piece has a humour about its hero that seemed to harken in a new age of reflexive humour within the genre. Scenes between Eastwood and Jose Cavo’s old sage innkeeper Silvanito are seeped in both humour and absurdity. The violence, too, speaks of a modernist era. For one thing, there are severed limbs and exit wounds; a new era emerges in movie violence.

As Eastwood tackles the mob, the audience is invited to take pleasure in the bad guys getting what comes to them more than in prior eras. Mostly, though, it is the music and character that defines the film. Morricone’s score moves to the editing and pace very precisely, great care seems taken to pace and feeling. With a younger star, and a younger feel, things would never quite be the same again in the western genre.

4. Death Rides a Horse (1967)

To watch Death Rides a Horse is to realise where Quentin Tarantino conceived of most of the Kill Bill saga. This film is as shameless a Spaghetti Western as one will see and is pitched at an intensely operatic tone. The film is grim rather than playful, opening in the dead of night and in heavy rain, and building towards murderous violence from the off. There are moments early on in particular that verge on the likeness of the horror genre.

The use of haunting memory is constant as the hero is burdened by his past, with musical cues repeating to imply the insistence of the dark memories in his mind. The style however, with dramatic zooms and cuts, and morbid iconography, is typical and flamboyant.

The film’s plot, centering on a young man who has waited years to avenge his family’s brutal murder, twists and turns and keeps you guessing. Lee Van Cleef, the most ubiquitous actor of the genre, stars as a slightly more sympathetic than usual hired gun who accompanies the young man; but he has a secret of his own. There are heads buried in sand, skull pendants, and endless use of the distinct Morricone score, particularly to both esculate tension and build upon the mystique of Van Cleef’s character. All in all, In Fact, the surprisingly tone of the film’s conclusion comes as a minor revelation in such a twisted tale of revenge incarnate.

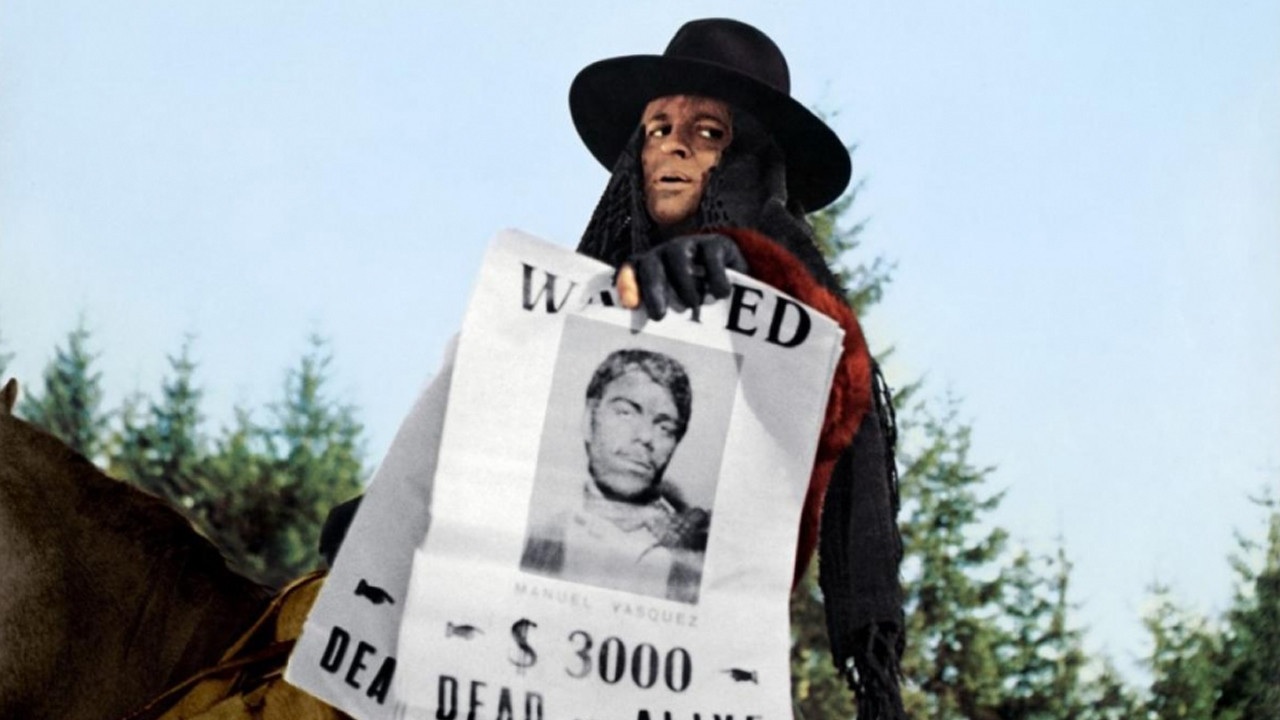

3. Django (1966)

The recent “spiritual remake” Django Unchained aside, this film was celebrated long before it’s myth was rebooted by Hollywood. The wandering, nameless antihero that has long been a staple of western mythology is brutally explored in Django.

Centering around the eponymous Django, the film opens with the title character trudging into a small town dragging a coffin behind him. Saving the life of a beautiful young woman named Maria, she becomes his ubiquitous companion as he is unwittingly caught up in a dispute between Mexican revolutionaries and a band of vile rebels. Romance, murder, and grand opera thus ensues in a western of effortless appeal to fans.

Similar in theme to A Fistful of Dollars, Django nonetheless reaps the benefit of Sergio Corbucci’s penchant for grand iconography. The Coffin, the beautiful belle, blood and beer glasses in an old saloon, and Franco Nero himself delivering the surly heroism of questionable rightiousness. These are very much the tools of genre for devotees.

Small moments like Django hiding on a couch as his darling Maria send a murderous mob in the one direction are well executed to the point of thrilling. A stand-off at an old bridge and a climactic shootout in a graveyard seem to be very indicative of what the genre represents in terms of grandeur. Django is a distinct grand vigilante movie in a genre of grand vigilante movies.

2. The Good The Bad and The Ugly (1966)

One of the most cited, homaged, and parodied spaghetti westerns, this film is one film that seems to define the many. Designed as a rapturous close to Leone’s Dollar Trilogy, this civil war crusade looks, sounds, and is performed in the very essence of the spaghetti western genre.

Every camera movement, cut, and musical flourish is carefully considered. for his part, Clint Eastwood’s film legacy was forever forged by his turn as the mysterious Man with No Name, a drifter and trick-turner who must beat his buffoonish ex partner Tuco and the murderous Mortimer to a vast graveyard across the state containing enough money to take any of them off of the beaten trail. For Leone, the greatest landscape to depict on film is that of an actor’s face. In this case, many critics believe the three rot agonists to be three sides of a disturbingly similar coin.

The high stakes are met with humour, caper and spectacle. Indeed, this film has many feathers in its cap in the annals of its genre. Ennio Morricone delivers his most instantaneous recognisable score in the form of the main theme. The introductory montage sets the standard for the genre, animated and scored to perfection. The conclusion is best described as being as wild and passionate as one comes to expect over the films course, yet still has the power to surprise.

The tragedy of Tuco’s family life adds unexpected depth to his character. There are famed moments like Tuco’s confusion over army uniforms and dynamite at a bridge that continue to linger with fans. Indeed, as the film’s wry final scene would suggest, this film delivers fan thrills with competence that is hard to match.

1. Once Upon a Time In the West (1968)

This is the film represented the beginning of a new trilogy for Sergio Leone and, in supplication, the beginning of a more character centred filmmaking. Legend has it that Leone even invited Clint Eastwood, Eli Wallach, and Lee Van Cleef to be in the now iconic opening scene- not as protagonists, but as the hired guns that get killed off in the opening stand off.

From the decadent pace setting of the opening set piece at the train station. to Henry Fondas Frank and his child murdering opening address, to Jason Robards Cheyenne and his self-proclaimed pat of Claudia Cardinale’s behind, much of his film has been the stuff of cinematic lore from the beginning. Crucially to the films following, though, it is also a thinking mans spaghetti western.

With Leones growing experience came greater character development, a distinctly complex female lead, and effortless iconography. On top of this, the story trades the violence of a civil war adventure of The Good, the Bad, and The Ugly for a more formative period of Americas history, situating the revenge saga in the midst of profound changes in the physical integrity of the United States.

The final shootout is earned by the films runtime and is romantic in its noting of death. For those new to its ending, it should be known that not all of the films conclusions are in keeping with traditional narrative satisfaction. The idea of the closing shot being that, for the many at least, the journey has been both a valuable and a tragic one. Yet, life in America continues for the better, the legacy being bigger than any one individual

Author Bio: Ross Carey is a Film Studies graduate from County Cork In Ireland. He is an award winning short filmmaker and is in the midst of writing his debut feature film. Before joining Taste if Cinema he was ran a popular blog entitled “Kino Shout! Films”. He will discuss the subject of film at any opportunity.