6. Playtime (1967)

Jacques Tati’s slapstick masterpiece Playtime (1967) was not only a positive look at the future of a consumer society, but remains one of the most joyful films ever made. The silent Monsieur Hulot (Tati) goes for a day out in an ultra-modern city, but what begins as a simple business appointment ambles off into a series of quietly observed tableaux vivant, including a World Expo-type trade show and various mishaps involving automation. We then spend the whole second half watching people slowly get drunk.

Remarkably, Tati built his city from scratch, at enormous personal cost, an optimism which infects every moment of the film. One of its great triumphs is that, despite being so incongruous with his surroundings, Monsieur Hulot is never left feeling like a lonely or alienated figure, since everywhere he goes he meets friendly faces who remember him from the old days, and who seem just as maladjusted as he is to the new hardware cluttering up their lives.

Despite the emphasis on imposing, modernist architecture, shot from impersonal distances, the film is never anything but warm and colourful, a delicacy of touch that helps make this perhaps the ultimate sci-fi to look at what it means, spatially and temporally, to explore the future.

7. 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968)

This film is divided into three chapters: We begin at the ‘Dawn of Man’, with a race of apemen being taught to use their thumbs by an object called the “black monolith”, and then jump forward to the eponymous year of the new millennium where modern homo sapiens meet the Monolith on the Moon. It directs them to the ‘Jupiter Mission’, before leading us ‘Beyond the Infinite’, ushering in a new evolutionary leap.

With 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968), Stanley Kubrick, working with writer Arthur C. Clarke, sought to create what he called the “proverbial, good science fiction film”. Few since then have managed to commit as fully as this one to a vision of the future, where people appear so at home in their unearthly surroundings that they sometimes barely register as human at all. In spite of its glacial abstruseness, the film marked a grand crescendo to the Space Race, positioning humankind’s first contact with extraterrestrial life as something no less ineffable than a journey into the mind.

Some would argue that the oddly mechanical behaviour of the people in 2001 makes it a coldly formal work of modernism rather than a humanist one. The main thrust of its plot involves a miscommunication between the human astronauts of the Jupiter mission and their artificially-intelligent supercomputer HAL, who effectively subjects Dr. Dave Bowman (Keir Dullea) to a Turing test. Judging him to have failed, and mistrusting his ability to handle first contact with aliens, HAL attempts to kill him. This would bode ill for Dave’s final encounter with the Monolith were it not that, from the moment of his arrival at the ‘Stargate’ to his ending as a ‘Star Child’, not one word is uttered. Prior to this, the most open and honest conversation in the film is held between a father and his infant daughter, giving it a sense of optimism which, far from diminishing after the year 2001, has only made it more approachable over time.

8. Close Encounters of the Third Kind (1977)

Steven Spielberg’s Close Encounters of the Third Kind (1977) is another film about first contact, made by a director who grew up watching movies where men meet aliens, argue amongst themselves, and then, usually, blow them up. Like 2001 before it, Close Encounters tries to imagine a different approach. Where Kubrick favoured silent, contemplative reverence, Spielberg opts for childlike wonder and grace.

Schlubby line mechanic Roy (Richard Dreyfuss) sees bright lights in the sky, imbuing him with strange visions and a new interest in UFOs, which distracts him until he gets fired and his family leaves him. Following his impulses, Roy blunders his way onto the sight of humanity’s first meeting with extraterrestrials, who reveal him to be their chosen passenger.

Slices of everyday life disrupted by otherworldly phenomena are intercut with the investigations of French scientist Claude Lacombe (Francois Truffaut), whose difficulty being understood by his U.S. military colleagues underlies the significance of the aliens’ communicating with Earth via the universal language of music, composed by John Williams. The film’s positivity extends to its government and army officials, typically bad guys in stories like this (they later would be in Spielberg’s E.T.), portrayed here as oddly quiescent.

This film can be seen to mark the point where Spielberg stopped being a New Hollywood director and became a brand unto himself, one whose trademark sentimentality is slightly less evident here, particularly in Roy’s callous abnegation of wife Ronnie (Teri Garr) – treated as a nagging obstacle to his dreams of becoming an astronaut – and his children. If the blokiness of the cast dates it, what does remain breathtaking are its extraordinary model effects by the late Douglas Trumbull, which ache to be seen on the biggest screen possible.

9. The Flipside of Dominick Hide (1980)

Broadcast in 1980 as part of the BBC’s Play for Today strand, The Flipside of Dominick Hide would now fall into the familiar sub-genre of romances involving time travel (Time After Time, Somewhere in Time, About Time). In the early 22nd century, when people have found the key to immortality, Dominick Hide (Peter Firth), a civil servant whose job is to observe the past, borrows a flying saucer from his work colleague and goes back to early 80s London to find a lost ancestor. He meets clothes shop manager Jane (Caroline Langrishe), and a whirlwind romance ensues.

The future, as envisioned by writers Jeremy Paul and Alan Gibson, is surprisingly well-realised on the low budget, including holographic television and an early version of Siri called ‘Sue’. It also tries to imagine the practical uses for time travel once it has become commonplace, being used mainly to improve historical databases.

Time-travel romances are often criticised for being creepy. This film harks back to the optimism of the 60s and has a hippyish sensibility, but can be seen as an attempt to address the consequences of that decade’s swinging. Dominick expects his wife to be cool about his affair with Jane, but accepts the need to take responsibility for his actions upon learning Jane is pregnant (with his lost ancestor). Dominick’s doe-eyed innocence also makes him an early inversion of the ‘born sexy yesterday’ trope.

By the early 80s, speculative sci-fi on both the big and small screens tended to be grim by default, but this film delights in reassuring its audience – just as Dominick promises Jane’s friends at her local pub – “I see a bright future.”

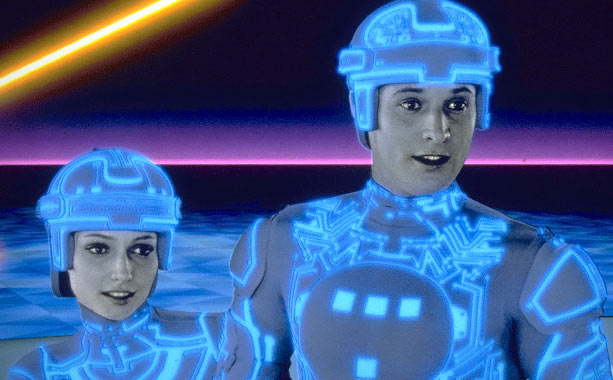

10. TRON (1982)

This film turns forty this year. For much of that time it was treated as a geeky, cult novelty, looked back on with a mix of condescension, respect, and the usual nostalgia, but deserves to be reappraised.

Computer genius Flynn (Jeff Bridges) sneaks onto the intranet of a corporation that stole his video game idea. The system’s artificially-intelligent nub, the Master Control Programme, prevents this by transporting him into the ‘computer world’, where programmes are sentient beings and human ‘users’ are deified. Flynn joins a rebellion to free cyberspace from the M.C.P. by – apparently – giving it a virus. The computer world then becomes a sparkling, utopian paradise.

It is easy enough to overlook the plot and dialogue of TRON if you stop to appreciate how fantastical it all looks. The infancy of CGI meant the computer world had to be created mostly through photographic effects, using a very time-consuming and fiddly method of ‘backlight compositing’, never again used to such an extent in a live-action film. This ensured that the Neo-baroque visuals of TRON have remained utterly unique. Director Steven Lisberger’s background in psychedelic animation leant the film its often heady sense of wonderment, together with the score by Wendy Carlos, which includes a chilling mix of synthesisers and the Royal Albert Hall Organ.

1982 was a vintage year for sci-fi and fantasy. Considered a box-office disappointment, TRON has always remained a cult gem, whose underground status was confirmed when Disney’s blockbuster sequel, the gloomy TRON: Legacy (2011), also underperformed. Not giving up, Disney has announced another film is on the way, but at a time when ideas such as the metaverse sound fairly dystopian, TRON’s imaginative promises of a brighter future for technology were forward-looking enough that its hopefulness still feels fresh.