From its very beginning, cinema has been obsessed with itself. Search ‘films about films’ on the internet, and you’ll be greeted with a host of the usual suspects: 8 1/2, perhaps the most famous film about filmmaking, pops up on every list written about films exploring the agony that goes into making a movie. Singin’ in the Rain and Sunset Boulevard offer a glimpse into the industry’s perception of its silent early days from the vantage point of the 1950s, a decades where American cinema was defined by the bright melodrama of the Hollywood musical and the chiaroscuro tones of the noir. And in silent cinema, we had films that explored the mechanics behind this new, solipsistic art form, such as Buster Keaton’s The Cameraman.

Clearly then, film is a vain art, and some of the most familiar movies are those that take an inward-look at the history and process of movie-making. Less explored, though no less important, are the films that tell us something about film itself: what it is, what it can do and what it can reveal to us. The films in this list offer a commentary on the meaning of film’s own apparatus. They explore cinema’s relationship with history; some tell us about how film mirrors human desire; others, about how it mirrors identity. Memory is a consistent theme throughout this list, as is the relativity of truth.

Here are nine films, each that use the medium in some way to make a bold commentary about what film is and what it can do. Some are more overtly ‘meta’ than others, whereas others were perhaps not made with these allegoric meanings in mind, instead having them thrust upon them in the years following the film’s release. However, each film listed, in its own unique way, tells us something about the potential of cinema and the ontology of the moving image.

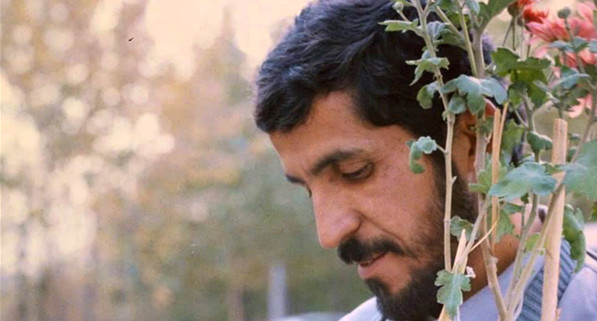

1. Close-Up (1990)

More than any other country, Iran has produced the greatest number of films exploring fact, fiction and that ambiguous, odd and often beautiful space in-between. Of those many films, Close-Up (1990) is probably the most famous. It tells the real story of Hossain Sabzian, a man “interested in art and film,” to use his words, who convinced a family, the Ahankhahs, that he was in fact famous director Mohsen Makhmalbaf (director of A Moment of Innocence, another film on this list).

As with every other film listed here, it’s not just the story that’s interesting; how that story presented to us is what makes the film fascinating. After getting caught, Sabzian was tried for fraud. Kiarostami was granted permission to film that trial. However, Kiarostami convinced Sabzian and the family to recreate the events that led to Sabzian’s arrest and subsequent trial in front of his camera. The result is a film that makes one question what is real and what is performance, and how far film penetrates our desire and identity.

A work of “docufiction”, Close-Up blurs the line between fact and fiction. However, in doing so, the film highlights how every film does this to an extent. They may not flout their hybrid nature to the same extent as Kiarostami does, but haven’t we learnt by now that every documentary film contains at least some degree of subjectivity? And, likewise, doesn’t every fiction film, no matter how fantastic or outlandish, tell us something about ourselves and our own experiences? “We can never get to the truth except through lying,” said Kiarostami. But we always end up at the truth. It just might not be the only one.

Like Persona, Close-Up deals with identity. Like Rear Window, it deals with desire. Like The Last Movie, it deals with how we internalise what we see on the screen. And, as with several of the films on this list, as well as Makhmalbaf’s own films, plus those of his daughter, Samira, most notably in her debut film The Apple (1998), it deals with the often tense relationship between fiction and reality. Film has given Sabzian an identity. Close-Up makes us question what role film has played in our own lives, as well as where the line between the real and the performed really stands and, most pressingly, how important the line really is.

2. Videodrome (1983)

The best example of the body horror genre, David Cronenberg’s Videodrome (1983) examines the effects of watching sinister horrors onscreen- all whilst embodying those very horrors. James Woods plays a television station CEO who seeks to trace the source of a broadcast signal, called Videodrome, that shows extreme violence and torture. It’s horrific, but we can’t look away. The puppet-masters of cinema have long-known this.

In many ways, Videodrome seems prophetic; the film seems a natural precursor to reality TV, smart phones and smart devices. But we can enjoy a cinematic reading from Videodrome too. As with The Last Movie, Videodrome examines the way we internalise what we see on screen. The more extreme that content is, the more likely it will change how we conduct ourselves and our relationships with others. The effect of a film need not end just because the final credit has rolled.

It’s not just the act of violence that permeates Videodrome; it’s the mode of transmission also. And here again we find parallels between our world and the twisted, surreal universe of Cronenberg/ Screens are everywhere. From the second we wake up turning off our alarms to that final video on YouTube before finally attempting to sleep, our days are consumed by the screen. Increasingly, it’s on these small screens where we watch our films. James Woods famously makes out with the television set in Videodrome, his face consumed by the seductive lips that have taken over the screen. Is such a visual metaphor even necessary today?

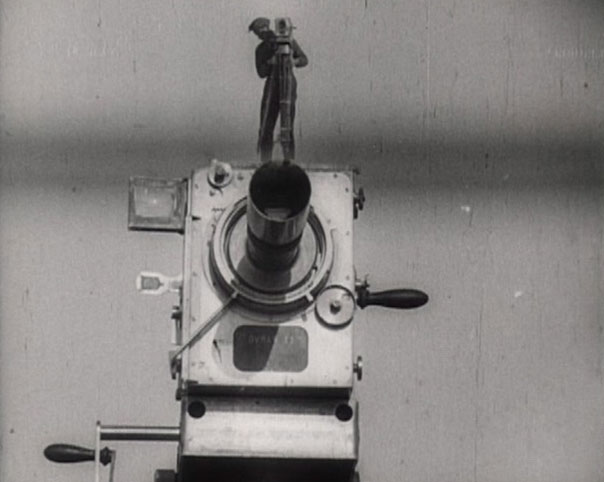

3. Man with a Movie Camera (1929)

The oldest film on this list and perhaps the most famous. Directed by Dziga Vertov in 1929, Man with a Movie Camera shows us what an urbanised existence looks like in the early Soviet Union. But to call it a documentary feels feeble. Rather, this is a raving montage, edited with the rushing enthusiasm of a drug-induced rave, deploying a range of cinematic techniques, some of which demonstrated for the first time in this film, all of which leaving the viewer, if not with a deeper knowledge of city life in the USSR, than an appreciation- if not necessarily an understanding- of what the camera is and what it can do. It has to be seen to be believed.

No more would cinema be perceived as the mere recording of reality, a means to film stories- an extension of books and theatre, rather than its own unique, damaged, beautiful being. Indeed, a series of title cards at the start of the film declare, “This new experimentation work by Kino-Eye is directed towards the creation of an authentically international absolute language of cinema on the basis of its complete separation from the language of theatre and literature.” (And they say the movies are getting dumber!)

So clearly, the topic of the film is its own mode of recording, rather than the thing it happens to be recording. (The title perhaps hints at this…) The film isn’t concerned with itself for vanity’s sake. For the Soviets, film was not a passing amusement to entertain the masses during their resting hours, as was the credo in the United States, but instead was a tool for revolutionary action and class solidarity. Like other Soviet films of the time, Movie Camera was made with revolutionary fervour, and the mad, rushing result was an attempt to inspire political consciousness as much as anything else.

However, whereas other Soviet films of the period, most notably those of Sergei Eisenstein, were more overtly propagandist, Man with a Movie Camera is unique in its aesthetic fervour. What one walks away with primarily is not an understanding of the day to day life of Kyiv, nor indeed a desire to overthrow the capitalist order, but instead that mad rushing feeling one gets when attempting to walk after a rollercoaster, or the loud silence one hears in the ears after coming indoors from a storm.

Here is an early film that makes no attempt to conceal its nature. In this mad symphony of a film (or is symphonies a better word?), we see a world of cinematic tricks, editing, montage and, in perhaps the most famous moment of the film, the camera, atop a tripod, walking. As though it were an infant, as though it were alive. Whilst past the earliest films of the Cinematographe, cinema was still in its infancy in 1929. And, like a child that has just realised they possess the powers of language and movement, the film is undeniably giddy at its own prospects and place in the world. Or, rather than a child, perhaps the film is more like a bashful teenager, screaming at the world, declaring its talents, boasting its potential. Don’t understand it? That’s okay. Here is a film that defies narrative logic and convention. Just look. Look and keep looking. We’ve been doing it for a century since.

4. Persona (1966)

Perhaps Ingmar Bergman’s greatest film- certainly his most thematically rich- Persona offers many questions and provides few answers. Unlike some of his other most famous works, Persona is not a long film. Yet, at just eighty six minutes, it manages to pack in more about identity, memory, history, psychology, sexuality, desire, fear and regret- and much more beautifully- than most other films could ever dream of.

But Persona also tells us something about the act of filmmaking itself. Indeed, the theme of cinema is presented to us from the opening shots. We are presented with the image of a projector warming up, before being shown a series of images which closely resonate with the images of Bergman’s past filmography. Indeed, throughout the film, we’re constantly reminded of the fact that we’re watching a film, most famously towards the middle of the film when the celluloid appears to break down in front of our eyes, before being subjected to another random series of images, only for the narrative to pick up again. And at the film’s close, we see a filmmaker and his camera crew. The final image of the film is once again of the projector, this time shutting down, bookending this inherently modernist film that quite literally from beginning to end told its audience that it was a film, not an objective portrayal of reality.

So clearly, Persona has something to say about cinema. (Tellingly, Bergman’s original title for the film was Cinematography, the film’s eventual title being a concession Bergman made to a worried producer.) What exactly that something is is still debated among fans and scholars alike, with the film being called the Mount Everest of film analysis. However, where things get even more complicated is where Bergman injects snapshots of reality into the fictional world of his 1966 film.

Two pivotal moments of the film spring to mind. The first involves one of the two central characters, Elisabet, watching footage of the famous self-immolation of a monk during the Vietnam War. The second involves the same character staring at the famous image of the liquidation of a Warsaw ghetto during the Holocaust. Why exactly Bergman chose to include these two images is a matter of great debate, and there isn’t the space to justifiably go into that here. But by including these real images into the fictitious world of the film, Bergman makes the audience question how far images- and by extension, cinema- can go to accurately represent violence and its legacy.